Federal and Confederate armies had engaged in three days of battle in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, July 1st to 3rd, 1863. The former, under Gen. George G. Meade, fielded about 94,000 men; the latter, under Gen. Robert E. Lee, about 72,000. Total casualties (killed, wounded, missing or captured) for each side were roughly 23,000, with 3,155 Federals killed and 4,708 Confederates.

Though Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia would get back into Confederate-held territory, his northward plunge was halted by Meade’s Army of the Potomac. On July 4th, Independence Day, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln sent an announcement by telegraph from the War Department:

The President announces to the country that news from the Army of the Potomac, up to 10 p.m. of the 3rd. is such as to cover that Army with the highest honor, to promise a great success to the cause of the Union, and to claim the condolence of all for the many gallant fallen. And that for this, he especially desires that on this day, He whose will, not ours, should ever be done, be everywhere remembered and reverenced with profoundest gratitude.

The “many gallant fallen” were not forgotten. By summer’s end, plans were made for establishing a cemetery at the site — the Soldier’s National Cemetery, as it was called at the time. President Lincoln was the last speaker to be invited; his invitation came from David Wills, a Gettysburg attorney heading the cemetery committee, who wrote to Lincoln on Nov. 2nd:

The Several States having Soldiers in the Army of the Potomac, who were killed at the Battle of Gettysburg, or have since died at the various hospitals which were established in the vicinity, have procured grounds on a prominent part of the Battle Field for a Cemetery, and are having the dead removed to there and properly buried. These Grounds will be Consecrated and set apart to this sacred purpose, by appropriate Ceremonies on Thursday the 19th instant, — Hon. Edward Everett will deliver the Oration.

I am authorized by the Governors of the different States to invite you to be present, and participate in these ceremonies, which will doubtless be very imposing and solemnly impressive. It is the desire that, after the Oration, You, as Chief Executive of the Nation, formally set apart these grounds to their Sacred use by a few appropriate remarks.

It will be a source of great gratification to the many widows and orphans that have been made almost friendless by the Great Battle here, to have you here personally! and it will kindle anew in the breasts of the comrades of these brave dead, who are now in the tented field or nobly meeting the foe in the front, a confidence that they who sleep in death on the Battle Field are not forgotten by those highest in authority; and they will feel that, should their fate be the same, their remains will not be uncared for.

We hope you will be able to be present to perform this last solemn act to the Soldiers dead on this Battle Field.

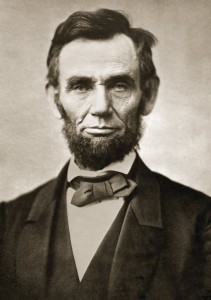

Lincoln began to write his speech in the White House. On Nov. 18th, he took a train from Washington City to Gettysburg. At one stop along the way, a little girl presented him with a bouquet of rose buds; kissing her, he said, “You’re a sweet little rose-bud yourself. I hope your life will open into perpetual beauty and goodness” (Lincoln, David Herbert Donald, 1995, p. 463). He put the final touches on his speech in Wills’s house on the town square, where he spent the night after declining to make a speech to the gathered crowd: “In my position it is somewhat important that I should not say any foolish things”.

Next morning, he wore a new black suit, his stove-pipe hat still trimmed with a black band of mourning for his son Willie, who had died in the White House more than a year and a half earlier (Feb. 20, 1862). And Lincoln had left another of his sons, 10-year-old Thomas, usually called “Tad”, at home in the White House seriously ill, though he would recover shortly. (Indeed, the president himself was getting sick, and would be quarantined for three weeks when he got back to the White House, with a mild variety of smallpox called varioloid.)

The dedication ceremony attracted a crowd at least 15,000 strong. Famed orator Edward Everett (who had been governor of Massachusetts, president of Harvard, U.S. Secretary of State, and a U.S. Senator) spoke for two hours, giving his speech from memory after weeks of preparation.

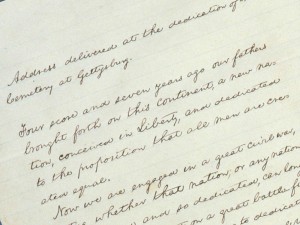

Wearing his spectacles, Lincoln spoke for less than three minutes; the photographer, expecting ample time in which to set up for the next photograph, was caught off-guard and failed to get a picture of the president giving his address in his high-pitched voice and faint Kentucky drawl:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

(That version is the “Final Text”, the last one we have in Lincoln’s own handwriting, the only one he signed; it is called the “Bliss Copy” after Alexander Bliss for whom Lincoln wrote it out some time in 1864. Its text is engraved on the south wall of the Lincoln Monument, and lacks the word “here” before “gave the last full measure of devotion”.)

The first-person singular pronoun — “I” — occurs not even once among Lincoln’s 271 words. Most of them are short, simple words of Anglo-Saxon derivation, rather than longer words derived from Latin. “Consecrate” and “dedicate” are notable exceptions, but Lincoln knew his audience was familiar with those words from their religious connotations.

The word “proposition” is another matter. Many writers have objected to Lincoln’s use of the word, thinking it too abstract or technical for the occasion; English writer Matthew Arnold supposedly threw down the address when he came to that word: “to the proposition that all men are created equal”.

But Lincoln had always thought of the American experiment as a proposition. The very first appearance of that word in Lincoln’s collected works is all the way back in 1838 when he used it in his first important political speech, talking about the generation that had fought the American Revolution (boldface added):

That our government should have been maintained in its original form from its establishment until now, is not much to be wondered at. It had many props to support it through that period, which now are decayed, and crumbled away. Through that period, it was felt by all, to be an undecided experiment; now, it is understood to be a successful one. Then, all that sought celebrity and fame, and distinction, expected to find them in the success of that experiment. Their all was staked upon it: — their destiny was inseparably linked with it. Their ambition aspired to display before an admiring world, a practical demonstration of the truth of a proposition, which had hitherto been considered, at best no better, than problematical; namely, the capability of a people to govern themselves. If they succeeded, they were to be immortalized; their names were to be transferred to counties and cities, and rivers and mountains; and to be revered and sung, and toasted through all time. If they failed, they were to be called knaves and fools, and fanatics for a fleeting hour; then to sink and be forgotten. They succeeded.

Thus, Lincoln shows us something of himself in choosing that word to use in his “few brief remarks” at Gettysburg; he shows how many long years he had pondered and pondered and pondered the ideas he was drawing out in his short speech — like a spool of yarn tightly wrapped but now being pulled out, measure by measure, sentence by sentence, in three paragraphs.

Lincoln’s words were both cheered and jeered. The newspaper Harrisburg Patriot & Union, a Democratic organ, infamously dismissed the speech in a Nov. 24th editorial: “We pass over the silly remarks of the President. For the credit of the nation we are willing that the veil of oblivion shall be dropped over them, and that they shall be no more repeated or thought of.” (That newspaper, now called the Patriot-News, has recently retracted its 1863 editorial.) Most of the criticism came from sources that were political opponents of the president or opponents of the war.

But its genius was recognized immediately, too. Edward Everett himself famously wrote to the president these congratulatory remarks the next day:

Permit me also to express my great admiration of the thoughts expressed by you, with such eloquent simplicity & appropriateness, at the consecration of the Cemetery. I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.

The ideas Lincoln drew from the American experiment, and drew out in his Gettysburg Address, have inspired men and women around the world for a century and a half. Indeed, author Peter W. Schramm wrote ten years ago about the speech’s connection to the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, quashed by the Soviet army:

The Hungarian Revolution against the Soviets and Communism of 1956 started on October 23, 1956…. By circa November 4th, the Soviets decided to move and that was that. The last free Hungarian radio station (maybe it lived until the 6th or 9th, I can’t remember) spent its last hours broadcasting the Gettysburg Address in seven languages, follow by S.O.S. The Hungarian gave the phrase “freedom fighter” to the world. May the 30,000 or so who died in those few weeks Rest in Peace.

Oh, yes, one more thing. I want to say “thank you” to my parents for having the courage and the foresight to leave the country and to bring their family (my sister was four years old and I was ten) to the United States of America. When I asked my father why we were going to the U.S., he said “Because we were born Americans, but in the wrong place.” Smart man, my father.

Indeed.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FsrDeGJUZdQ]