In the mid-’90s, the abortion industry in the United States realized it was facing an existential threat — the population of abortionists was aging and nobody was stepping up to take their place. Although plenty would pay lip service to a right to “choose,” when it came to the grisly work involved in “terminations,” few medical students were willing to partake. This trend has yet to reverse.

In the mid-’90s, the abortion industry in the United States realized it was facing an existential threat — the population of abortionists was aging and nobody was stepping up to take their place. Although plenty would pay lip service to a right to “choose,” when it came to the grisly work involved in “terminations,” few medical students were willing to partake. This trend has yet to reverse.

Initially, this realization led to two efforts: the first was an attempt, through accreditation requirements, to force medical students to learn how to perform an abortion in order to graduate. Fortunately, Congress intervened in 1996, outlawing any such requirement.

The second effort was to import the abortion drug RU-486 from Europe. Chemical abortion seemed especially promising: because it is not a surgical procedure, one abortionist could preside over several abortions occurring at the same time, monitoring for complications rather than actually doing the work of emptying wombs by force. This development was perceived to be so important that President Clinton personally appealed to the French makers of the drug to bring it to the US market. His FDA fast-tracked its approval.

But there were complications. Chemical abortion appears to be 10 times riskier than surgical abortions that are performed in the same gestational window. More often than one might think, these are incomplete, resulting in severe hemorrhaging. Women risk dying of a sepsis-like disease, as the drugs that block the nourishment of the baby also appear to block the immune response to infection. As an experience, it is less like a minor surgery and more like a mini-labor, where women unexpectedly come face-to-face with the “products of conception” they pass, often at home, which by eight or nine weeks look more like a baby than anything else.

This is not to say abortionists have abandoned surgical abortion. Big Abortion needs it. This is only to say that chemical abortion is not the magic pill the industry hoped it would be. As it must rely more on these abortions, though, people will increasingly come to know the truth that this is an ugly intervention.

Major demographic and legal changes have occurred since the 1990s. The majority of Americans are now pro-life. At the state level, new restrictions on abortion are passed every year. What had begun as a theoretical problem for Big Abortion is now maturing into a genuine crisis: to survive as a business model, Big Abortion must rely less on surgical abortion, less on chemical abortion, and even to prepare for a day when abortion is no longer legal in the United States.

What to do, then?

Big Abortion is increasing its international efforts, intervening, directly or through its State Department proxies, in the drafting of foreign constitutions, litigating in international court, and engaging in diplomatic efforts at the United Nations. Technology allows abortionists in third world countries to perform an abortion where there is no electricity.

For Big Abortion, the focus has clearly turned to conventional contraceptive pills and other hormonal interventions.

This marks a shift for the industry. Although abortionists were historically able to profit from contraceptive pills, this was not their chief source of income. According to current prices ($12 for the pill, $500 for an abortion), it takes up to 50 months of repeat patronage for contraceptive pills to bring in the revenue earned by a single abortion. Contraceptives are best used in the same way as a “loss leader,” except that it is never necessary, thanks to government programs and health insurance, for Big Abortion to incur a loss. In any population where women use contraceptives, they are also creating a pool of potential customers for their most expensive “service.”

Americans for the most part are now familiar with how this works. Young women can walk into a clinic and at their first visit get one to three months of birth control for free. Big Abortion charges the government. This builds trust between the potential customer and the provider, and through a phenomenon known as “risk compensation,” (e.g., people drive faster when wearing seatbelts) studies show these women are now more likely to engage in sex outside of a stable, committed relationship, making them, for the first time, potential customers for abortion.

With failure rates as high as 48% for certain segments of the population, but only dipping as low as 6% for the first year of typical use (the average is 8%), the pill guaranteed a steady stream of women who were pregnant without intending to be. Although it was possible to make some money by providing the pill to responsible, fastidious women in committed, long-term relationships, why would they try? To focus on this would be counter-productive, when the real profit was in its incorrect, inconsistent use. This publicly subsidized, privately profitable nexus is how the industry made its money for decades.

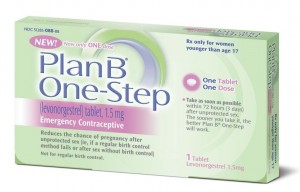

In 1999, though, there began a shift in Big Abortion’s profit structure, with the introduction of the Plan B “morning after” pill. Known as an intervention since the 60s, nothing was preventing doctors from directing women to take several days’ worth of contraceptives if they missed a dose, and indeed many were. Nonetheless, a public-private partnership including five Planned Parenthood affiliates obtained an FDA license to market the product anew. Barr Pharmaceuticals eventually bought it out, but only with assurances that they would market the product at a price above what Planned Parenthood charges, so Planned Parenthood could undercut the competition. With these updated FDA licensing and marketing deals, it was possible for Big Abortion to approach the intervention according to the rules of a new price structure. Planned Parenthood could profit first by providing it to itself, (charging the government more than conventional contraceptives), and later by undercutting the rest of the market, at a markup of $20 for each course. With Plan B, there is no waiting until the woman has a positive pregnancy test. Just the suspicion that there might be a hiccup in a woman’s regular birth control method suffices for the cash to start flowing to Big Abortion. Stock up, they say, just in case.

In 2010 came the introduction of Ella, which is similar to the Clinton-era chemical abortion, but women use it like Plan B and it is “effective” for a longer period after intercourse. Women are encouraged to take it whether they know themselves to be pregnant or not, as a “preventive” measure that is likely to cause an abortion, but this time without the recognizable humanity passing into the toilet.

And finally we have the last piece of this shift in the Big Abortion profit structure. With the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), Big Abortion appears to be gaining a new price point for conventional contraceptives. Politicians are wringing their hands that women will be forced to pay between $50 and $80 a month for their pills, which is less a reflection of the real world and more a reflection of the world they want to impose on women who use their products. Court documents from 2004 litigation reveal that Planned Parenthood charges $12 a month for their most popular oral contraceptives. A call to any drug store suggests it’s possible to get by for $4 to $9. In any case, drug manufacturers are required under federal law to provide these drugs to Big Abortion under price controls — typically between $1 and $3 for a monthly dose. Under PPACA, it’s apparent that it is now going to cost insurers $60 a month for these “free” contraceptive pills.

And finally we have the last piece of this shift in the Big Abortion profit structure. With the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), Big Abortion appears to be gaining a new price point for conventional contraceptives. Politicians are wringing their hands that women will be forced to pay between $50 and $80 a month for their pills, which is less a reflection of the real world and more a reflection of the world they want to impose on women who use their products. Court documents from 2004 litigation reveal that Planned Parenthood charges $12 a month for their most popular oral contraceptives. A call to any drug store suggests it’s possible to get by for $4 to $9. In any case, drug manufacturers are required under federal law to provide these drugs to Big Abortion under price controls — typically between $1 and $3 for a monthly dose. Under PPACA, it’s apparent that it is now going to cost insurers $60 a month for these “free” contraceptive pills.

Over the years, then, the approach has changed, but the result is the same. Instead of relying so much on the profit from abortion, Big Abortion now has increased the interventions for each customer and increased or secured the profit from each of these interventions. Instead of $10 a month for the pill until a customer errs and comes in for a $500 abortion, Big Abortion can gain $40 or $50 dollars every month for her regular method plus $20, $30, or $40 dollars every time she thinks she might have erred. If she remains with child after the first week in spite of this hormonal assault, she can fall back on the more traditional chemical abortion, or even surgical abortion as long as she can find one of the dwindling number of providers.

There seems to be no way to square this framework of exploitation — first for sex, then for money — with any true and objective view of women’s liberation or health. Perhaps the needed overhaul is not in Big Abortion’s profit structure, but rather the entire understanding of what it means to respect women and their well-being.

This article first appeared on Zenit.org as part of HLI America’s Life Watch series.