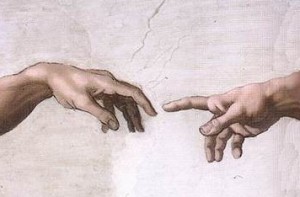

Adam and Eve really did have it easy. They were so comfortable in their human skin. More to the point, they were comfortable in their human skin which had a spiritual soul. This did not seem odd or cause them any kind of dilemma, stress, or confusion. They were created to be perfectly at ease living, as it were, with each leg in a different world, material and spiritual, temporal and eternal.

Adam and Eve really did have it easy. They were so comfortable in their human skin. More to the point, they were comfortable in their human skin which had a spiritual soul. This did not seem odd or cause them any kind of dilemma, stress, or confusion. They were created to be perfectly at ease living, as it were, with each leg in a different world, material and spiritual, temporal and eternal.

It’s not so easy for us. Since Adam and Eve lost that natural ease of combining two different realms of existence in one human being, life for us humans has become decidedly more complex.

This difficulty we struggle with struck me anew as I was reading Christopher Dawson’s book, The Dividing of Christendom. It’s an account of what happened in Europe leading up to, including, and after the Reformation. What struck me most forcefully were not the Reformation itself and all its consequences. What struck me was the struggle the Catholic Church had with the world.

St. John has some critical things to say about the world:

Do not love the world or the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, love of the Father is not in him. For all that is in the world, the lust of the flesh and the lust of the eyes and the pride of life, is not of the Father but is of the world (1 Jn 2:15-16).

Reading the history of the Church in the latter Middle Ages, it is difficult not to notice that many people in the Church, from popes to peasants, were ensnared by these three sins St. John lists. And, yes, who of us does not struggle with these temptations even today? It is said that we should be in the world but not of it. That’s easier said than done, don’t you find?

The trouble is we are made of the same stuff as the world is made. We are material beings as well as spiritual beings and we rely on material things for our very existence. We have to go out into that world to make a living. The temptation is to go to either extreme, to buy into the material world for all we are worth, or to see everything material in the world as evil.

Clearly, St. John did not mean that the material world was evil, for God created the world and declared it was good. Anything God creates must be good. So the key word must be “love.” “Do not love the world or the things in the world.” This doesn’t mean we can’t take pleasure in the things of this world, because God created us to be able to experience pleasure in His creation, nor does it mean we can’t desire them, because this too is natural to us as God created us.

What it does mean is that we can’t desire material things or pleasure more than we desire God, we can’t have an inordinate (out of the proper order) desire for things or pleasure. God calls us to be detached from the material world, to be willing to give up anything for Him. But this is a delicate dance for most human beings. We are dependent upon the material world, and yet we are not to be attached to it. That is difficult. For one thing, we are “attached” by the very fact that we are material. As a silly example, I am literally attached to the earth by gravity. I am also attached to food in order to live. The key is that our hearts are not to be attached.

This brings us back to the word “love.” We usually think of love as a thing of the heart, and so it is in this case. If we “love the things of this world,” we have given our hearts to them, and our hearts should be given ultimately to God, not purely material creations or pleasures.

Going back to Dawson’s book, it struck me that just as I struggle between living a material existence and a spiritual existence, so does the Church, not just in the Middle Ages but in all ages. She too must live in the world without being of the world. Of course, the Mystical Body of Christ is spiritual, but the Body of Christ is also material. We see it at every Mass. We also see it in the Church, that organization made up of people. We can make either of two mistakes by either over focusing on the spiritual side of the Church, as if that was all there was to “Church,” or by focusing too much on the material side.

One of the beauties of the Catholic Church is that she does embrace God’s material creation as something good. She uses art, music, and architecture, not as if they were necessary evils, but in their full, material beauty and goodness. She also uses the material world in her sacraments, rituals, and liturgy. She combines the two worlds of material creation and spirit, but it is a delicate dance for her too.

This dance became quite a great struggle during the Middle Ages, as Christopher Dawson points out. The Church’s partner, either the state or some ruling prince, was often a very aggressive partner, wanting to control the whole dance. For her part, sometimes the Church was too willing a partner or tried to control the whole dance herself.

The Church has learned from that experience, but the dance must still go on. The dangers are still there, both from nations where the Church is still seen as something to be controlled, and on the part of Church faithful where there is an over emphasis on the material side of her nature.

The size of a congregation or the size of the actual church does not indicate how holy it is. The world measures success, God measures holiness. The human desire to better things can become troublesome. We want better evangelization, better choirs, better administration of parishes and dioceses, better homilies, better social services, better churches and grounds, better schools. But what is better? Does it mean holier? The Church, after all, is meant to be the means of our holiness.

While holiness might not require material resources, evangelization and the life of the Church do. The Church too lives with a leg in both worlds. What a mystery. Why did God design it like this? I don’t know, but I think it is beautiful that God has made His Church to resemble our condition so closely. And it only makes sense, because the Church is the Body of His Son, and he asked His Son to share our predicament — the predicament that was not God’s creation, but was brought about through sin. And the Son did, because He loves us odd beings.

(© 2011 Pat Gillespie)