The year 2011 witnessed a new wave of protest movements and unprecedented popular outrage across the globe. From the protests in North Africa and the Middle East to the Occupy Wall Street movement in the United States to the camps outside St Paul’s Cathedral in London and Moscow, demonstrators have expressed a deep-seated anger at global finance that is shared by many.

Worldwide, there is an implicit, inchoate awareness that big government and big business have colluded at the expense of the people. Both central bureaucratic states and unbridled markets are disembedded from the mediating institutions of civil society, and civil society is subjugated to the global secular “market-state.”

This convergence of state and market can be described as secular because it subordinates human relationships, civic ties and social bonds to abstract values and standards such as commercial exchange or centralised regulation. Ultimately this subjects the sanctity of life and land to the combined power of state and market and threatens the autonomy of both civil society and faith groups.

Thus twenty years after the demise of Soviet state communism, the global recession into which free-market capitalism has plunged the world economy provides a unique opportunity to chart an alternative path. Both the left-wing adulation of centralised statism and the right-wing fetishisation of market liberalism are part of a secular logic that is increasingly contested. It is surely no coincidence that the crisis of global capitalism occurs at the same time as the crisis of secular modernity.

The collection of essays I have recently published, The Crisis of Global Capitalism, outlines a new political economy that rejects capitalism in favour of civil economy – that is, a market economy that is firmly embedded within the mediating institutions of civil society.

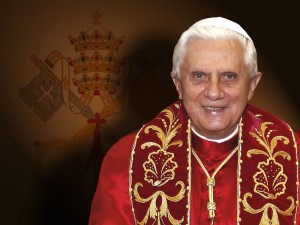

The idea of civil economy draws on Pope Benedict’s social encyclical Caritas in veritate, which was published in 2009. Building on the tradition of Catholic social teaching since the groundbreaking encyclical Rerum Novarum (1891), Caritas in veritate is the most radical intervention in contemporary debates on the future of economics, politics and society.

Publication of the long-awaited papal encyclical in some sense re-ignited the struggle for the soul of Roman Catholicism, as Tracey Rowland showed in her contribution to the collection of essays. On the one hand, there are the neoliberals like Michael Novak and the theo-cons like George Weigel who denounce “the economic heresies of the left” and dismiss the Pope’s injunction against unbridled free-market capitalism. On the other hand, there are the liberation theologians and “social-democrat” Catholics who ignore Benedict’s critique of the centralised bureaucratic state and yearn for statist solutions to get the world out of the recession.

In contrast with both these factions, the Pope has charted a Catholic Christian “third way” that combines strict limits on state and market power with a civil economy centred on mutualist businesses, cooperatives, credit unions and other reciprocal arrangements – a vision that John Milbank’s chapter explores and develops. By advocating an economic system re-embedded in civil society, the Pope proposes a political economy that transcends the old, secular dichotomies of state versus market and left versus right.

The commonly held belief that the left protects the state against the market while the right privileges the market over the state is economically false and ideologically naive. Just as the left now views the market as the most efficient delivery mechanism for private wealth and public welfare, so too the right has always relied on the state to secure the property rights of the affluent and to turn small proprietors into cheap wage labourers by stripping them of their land and traditional networks of support.

This ideological ambivalence masks a more fundamental collusion of state and market. The state enforces a single standardised legal framework that enables the market to extend contractual and monetary relations into virtually all areas of life. In so doing, both state and market reduce nature, human labour and social ties to commodities whose value is priced exclusively by the iron law of demand and supply.

However, the commodification of each person and all things violates a universal ethical principle that has governed most cultures in the past – nature and human life have almost always been recognised as having a sacred dimension. Like other world religions, Catholic Christianity defends the sanctity of life and land against the subordination by the “market-state” of everything and everyone to mere material meaning and quantifiable economic utility. In my chapter, I argue that this was first advanced by the civil economists of the Neapolitan Enlightenment and further developed by Christian “socialists” like Karl Polanyi and his Anglican friend R.H. Tawney – an argument further advanced in John Hughes’s contribution on Anglican social teaching.

Crucially, the Pope writes in the encyclical:

“the exclusively binary model of market-plus-state is corrosive of society, while economic forms based on solidarity, which find their natural home in civil society without being restricted to it, build up society.”

Instead of defending civil society in its current configuration, Benedict calls for a new kind of settlement whereby the global “market-state” is re-embedded within a wider network of social relations and governed by virtues and universal principles such as justice, solidarity, fraternity and responsibility.

Concretely, the Pope seems to encourage the creation of enterprises operating according to mutualist principles like cooperatives or employee-owned businesses, for example the Spanish-based cooperative Mondragon which has over 100,000 employees and annual sales of manufactured goods of over $3 billion. Such businesses pursue both private and social ends by reinvesting their profit in the company and in the community instead of simply enriching the top management or institutional shareholders.

Benedict also appears to support professional associations and other intermediary institutions wherein workers and owners can jointly determine just wages and fair prices.

Against the free-market concentration of wealth and state-controlled redistribution of income, most essays in the collection propose a more radical programme in line with the Pope’s encyclical: labour receives assets (in the form of stake-holdings) and hires capital (not vice-versa), while capital itself comes in part from worker and community-supported credit unions rather than exclusively from shareholder-driven retail banks.

Like the “market-state,” money and science must also be re-embedded within social relations and support rather than destroy mankind’s organic ties with nature, as David Schindler’s chapter on the anthropological dimension of Caritas in Veritate suggests. As such, the world economy needs to switch from short-term financial speculation to long-term investment in the real economy, social development and environmental sustainability.

Taken together, these and other ideas developed in the encyclical go beyond piecemeal reform and amount to a wholesale transformation of the secular logic underpinning global capitalism.

Alongside private contracts and public provisions, Benedict seeks to introduce the logic of gift-giving and gift-exchange into the economic process – an idea that Stefano Zamagni highlights in his contribution to the volume. Market exchange of goods and services cannot properly work without the free, gratuitous gift of mutual trust and reciprocity so badly undermined by the global credit crunch.

Pope Benedict XVI’s call for a civil economy represents a radical “middle” position between an exclusively religious and a strictly secular perspective. Faith can lead to strong notions of the common good and a belief that human behaviour, when disciplined and directed, can start to act more charitably.

There can also be secular intimations of this: the more faith-inspired practices are successful even on secular terms – such as greater economic security, equality, sustainability, civic participation – the easier it will be for secular institutions to adopt elements of such an overarching framework without however embracing its religious basis.

Thus, Benedict’s vision for an alternative political economy resonates with people of all faiths and none.

[Editor’s Note: this article first appeared at ABC Religion & Ethics.]