In an opening scene of Brian Helgeland’s moving film, 42, Branch Rickey, the famous president of the Brooklyn Dodgers and played by Harrison Ford, is reviewing files of potential black baseball players whom he might bring into major league baseball in the face of inevitable hate, vitriol, and racism. He picks up Jackie Robinson’s file.

In an opening scene of Brian Helgeland’s moving film, 42, Branch Rickey, the famous president of the Brooklyn Dodgers and played by Harrison Ford, is reviewing files of potential black baseball players whom he might bring into major league baseball in the face of inevitable hate, vitriol, and racism. He picks up Jackie Robinson’s file.

“He’s a Methodist,” says Rickey. “I’m a Methodist. God’s a Methodist.”

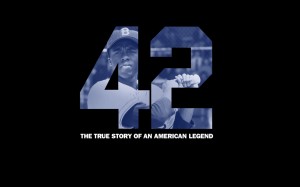

Robinson was, like Rickey, a devout Methodist who could also hit and run the bases like few others. 42 is the story of how these two broke the color barrier which deprived America’s pastime of the talent of men like Robinson, who is played by Chadwick Boseman in this newly released film.

St. Louis Cardinals fan have always held Branch Rickey in high regard. He has a star in his honor located at 6631 Delmar in St. Louis, part of the St. Louis Walk of Fame. The following description of Rickey’s contribution to the Cardinals comes from the Walk’s website:

Often called the greatest front-office strategist in baseball history, Branch Rickey came to the Cardinals in 1917 and turned a losing team into a powerhouse. Believing that “luck is the residue of design,” he developed the modern farm system that brought the Cardinals nine pennants and six World Series through the 1940s. After moving to the Brooklyn Dodgers, Rickey signed Jackie Robinson and brought him to the majors in 1947; more black players soon followed. Branch Rickey simultaneously broke baseball’s color line and built the great Dodger teams of the 1940s and 1950s, ensuring his induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Arguably, without Branch Rickey’s labors to get Jackie Robinson into the Majors, the Cardinals would not have had Bob Gibson and the other upstarts who beat the New York Yankees in the 1964 World Series, a story told by David Halberstam in October 1964 (1994). (I have previously written about my brother and me attending the seventh game of that Series here.)

Harrison Ford’s Branch Rickey is convincing. He plays it with humor and an honest, but not overbearing, religiosity, true to the man and his times. When the owner of the Philadelphia Phillies threatens to keep his team off the field if Rickey plays Robinson, Rickey tells him that, when he dies and faces judgment before God, saying you kept your team off the field because you didn’t want to play against a black man was not going to be “sufficient.”

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal by Chris Lamb, a journalism professor at Indiana University (Indianapolis), documents the strength of both Rickey’s and Jackie Robinson’s Methodist faith, their pole star throughout their lives.

Lamb cites a 1950 interview in which Jackie mentioned his kneeling down every night to pray before going to bed. “‘It’s the best way to get closer to God,’ Robinson said, and then the second baseman added with a smile, ‘and a hard-hit ground ball.’”

This movie will be characterized as “uplifting” and “moving,” which is often the kiss of death for the intelligentsia. It is both uplifting and moving. It is also a compelling and engrossing film, effectively combining two different genres, the heroic baseball story and the long-suffering quest for racial justice. This film is a very different thing from director Brian Helgeland’s previous work, much of it as a screenwriter, in productions such as L. A. Confidential (1997) and Mystic River (2003).

42 provides the excitement of traditional game sequences, especially base-stealing and fielding, while re-creating that now alien world of separate bathrooms for white and black people, riding at the back of the bus, and overt and abusive racism that is unthinkable in America today. Younger moviegoers will probably find it all hard to believe midway through the presidency of Barack Obama.

I was struck by the cinematography and editing of Robinson’s base-running and relentless stealing of second base, third base, and sometimes home plate. These shots would shift rapidly, seamlessly from wide angle, covering the throw to the bag, and then focusing very tightly, at ground level, to capture the runner’s face crammed up against the bag, next to the defender’s foot with the glove right on him. The umpire seemed always to be hollering “Safe!”

There were, of course, dramatic match-ups between Robinson and evil pitchers trying to take his head off with dangerous pitches. We have seen these before in baseball movies, but the social context infuses these confrontations with even greater intensity and drama.

Chadwick Boseman as Jackie Robinson is a wonderful, handsome and of great physical stature, with simmering rage, tightly controlled, per Rickey’s wise and prescient counsel. He needed a player, a black player, “with the guts not to fight back” and stay focused on playing great baseball.

Nicole Beharie, playing Rachel Robinson, is beautiful, witty, and matches Jackie’s courage and resolve with trust and faith in her husband. These two make a remarkable couple on screen and, in the Hollywood of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s would, for sure, be marked for a string of hit movies. This may not be in the cards, but we need to see more of these fine actors either separately or in tandem, preferably the latter.

Andre Holland does a great job as Robinson’s Boswell and black sportswriter assigned by Rickey to lookout for the headstrong player and his strong-willed wife. He has to balance his typewriter on his lap while sitting along the third base line since he was not allowed in the press box.

Law and Order’s Christopher Meloni, playing Leo Durocher, does a nice job in a small but critical role as the womanizing manager who, at Rickey’s direction, smacks down a player’s rebellion over playing with a black man. He is also given a short homily by Rickey regarding the Bible’s teaching on adultery, but his affair with a Hollywood starlet leads to a yearlong suspension just when Rickey needed him the most. The CYO (Catholic Youth Organization) threatened a boycott of baseball unless Durocher was censored by the Commissioner. Times have changed.

Ryan Merriman as Dixie Walker and Lucas Black as Pee Wee Reese make up part of a supporting cast that brings that era of baseball to life. Walker originally resented Robinson but came around as the 1947 season progressed. Reese stood with Robinson. The film features a scene in Cincinnati, right across the river from Kentucky, Reese’s home state, in which he ostentatiously puts his arm around Robinson to show his solidarity with Robinson for the benefit of his fellow Kentuckians. This includes a humorous exchange in which Reese talks about how “we” lost the Civil War but will have better luck next time. Robinson responds, “Good luck with that, Pee Wee.”

Slavery and racial prejudice have been called America’s Original Sin. 42 tells the story of at least partial redemption after the Fall in one small segment of society, professional baseball. Lovers of America and its greatest pastime will enjoy this movie.