I’ve noticed a curious tic in my circle of friends. We’ve known each other for years, we share the faith, a worldview, and a trail of conversations on almost every subject, and yet, there are moments where we stop mid-sentence to adjust our words, the delivery, or the approach to a topic that is currently hotly debated. It might be marriage, the nature of human love, opinions about what children should or shouldn’t see, the propriety of public displays of affection, proposed pieces of legislation, homilies heard here or there, what is being taught in various schools, or any number of themes that eventually bump up against “the one love that trumps all other loves”—meaning same-sex attraction and the actions that flow from it.

I’ve noticed a curious tic in my circle of friends. We’ve known each other for years, we share the faith, a worldview, and a trail of conversations on almost every subject, and yet, there are moments where we stop mid-sentence to adjust our words, the delivery, or the approach to a topic that is currently hotly debated. It might be marriage, the nature of human love, opinions about what children should or shouldn’t see, the propriety of public displays of affection, proposed pieces of legislation, homilies heard here or there, what is being taught in various schools, or any number of themes that eventually bump up against “the one love that trumps all other loves”—meaning same-sex attraction and the actions that flow from it.

While Catholics may agree on what constitutes a marriage, and what creates the healthiest atmosphere for children, there is now a self-consciousness manifesting itself everywhere—even in private conversations. Everyone I know wants to be loving, wants to be fair, and wants to share the truth about the beauty of God’s self-revelation, and yet there is so much opprobrium about “hateful Christians” and “homophobia” that we’re not even sure how to express ourselves without crossing a line. Most of our fellow believers have yet to make peace with a fact recently noted by Fr Dwight Longenecker:

The idea that being a Catholic might involve any sort of conflict with the surrounding culture or clash with the prevailing culture is something that has never once entered their heads.

And yet here we are. There is no way to soften the message—or massage it, or otherwise deliver it—so that it will be received with gratitude or understanding amongst those whose hearts remain closed to God’s truth. The Catechism teaches:

The marriage covenant, by which a man and a woman form with each other an intimate communion of life and love, has been founded and endowed with its own special laws by the Creator. By its very nature it is ordered to the good of the couple, as well as to the generation and education of children (#1660).

While this truth can be said gently, roughly, kindly, insensitively, carefully or in haste, there are those who are going to take offence no matter how it’s phrased. Thus we have come to an impasse concerning the institution of marriage which doesn’t bode well for Christians, because at this point in history deconstructionists are clearly in the ascendency.

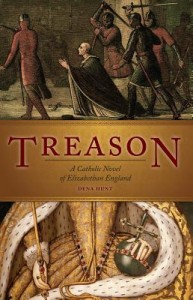

All of this was on my mind as I read the lovely story contained in Dena Hunt’s Treason (Sophia Press). Most of us are familiar with the tragic outline of England’s persecution of Catholics in the 16th century: Henry VIII married Catherine of Aragon, who gave birth to a daughter, Mary. In hopes of a male heir, Henry divorced Catherine and attempted marriage again—despite the firm opposition of the Church, which defended the bond between Henry and Catherine. Rejecting the Church’s authority, Henry proclaimed himself head of the Church of England, which would countenance his divorce and remarriage. Elizabeth I was born of his subsequent union with Anne Boleyn, but Elizabeth’s eventual accession to the throne meant that all Catholics were guilty of treason for their Church’s opposition to her father’s action and her authority.

Even when Catholics remained quiet about political affairs and simply wanted to attend Mass in peace, their very existence was a threat to Elizabeth. She required that their altars be smashed, their church property be confiscated, and their priests be killed in degrading and painful ways. It was in this crucible of persecution that each layman had to pick his way—according to his strength and conscience—and this is what makes Treason so compelling, for within its pages lie a range of responses, a measure of confusion over what constituted prudence, and fluctuating stances from day to day, even from hour to hour within any given person. We are a complex and fickle lot, to be sure.

The story encompasses one small village and a mere seven days, but there is enough breadth and scope to create a memorable saga. The characters all struggle, which makes them compelling. There are no cardboard saints or simplistic villains. Surely some are more self-aware and noble, but the value in this book is that it can be instructive for our difficult days ahead.

Once again marriage—the primordial sacrament—is causing division. Jesus rebuked the Jews for their hardness of heart about the indissolubility of marriage, Protestants long ago parted company with the Catholic Church about divorce and remarriage, many Christian confessions have made peace with same-sex unions, and the rest of the world hardly lifts and eyebrow over cohabitation, promiscuity, and polygamy.

The Church stands alone in defending the bond, and her members wonder how to navigate a landscape that is both unfamiliar and all too familiar. Our Lord said, “If the world hates you, realize that it hated me first” (John 15:18). While we must pray about how best to express the truth, we cannot be shocked when the truth is met with derision, rage, and even violence. It’s a privilege to suffer for the truth, as the characters in Treason show, and it would be an excellent meditation on the inevitable conflicts to come.