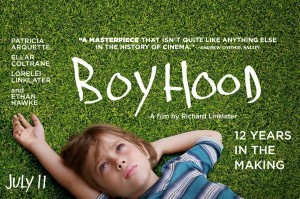

Boyhood, the new movie written and directed by Richard Linklater (Waking Life, A Scanner Darkly, The Before… Trilogy with Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy) is a one-of-a-kind, “big idea” film. The lives of screen Mom, Dad, son and daughter are followed for twelve years. Literally twelve years, having been filmed for about a week each year.

Boyhood, the new movie written and directed by Richard Linklater (Waking Life, A Scanner Darkly, The Before… Trilogy with Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy) is a one-of-a-kind, “big idea” film. The lives of screen Mom, Dad, son and daughter are followed for twelve years. Literally twelve years, having been filmed for about a week each year.

We watch the actors seamlessly grow and age on screen. Mom is Patricia Arquette (who played such a believable Mom in the TV series Medium), Dad is Ethan Hawke, the son and main focus is Ellar Coltrane (a Texas native, where the film is set), and the daughter is Linklater’s own daughter, Lorelei. The cast, including the minor roles, are superb.

This film is worth seeing for its “handle with care” approach rather than “brutal honesty” voyeurism as we peer into a family’s intimate inner workings. If you like very “human” filmmaking, “take your time” drama that believes life and people are made up of a myriad of minute moments, this film is for you.

One of my favorite things about this movie is that we see how Mason, the “boy” in question, doesn’t really change a whole lot from who he was as a kid. He just grows more into himself, fleshing out his ideas about how life should/could be. There is a lovely acceptance (albeit bumbling) by all the characters of what they can’t control and what they can.

The words “responsible” and “responsibility” are used at least 75 times. It becomes almost a joke that it’s impossible the writer-director is unaware of. Mason’s mom uses the terms over and over with reference to herself, and all kinds of adults and mentors advise Mason that this is exactly what he is lacking despite his other good qualities. Mason gets a lot of pep talks. (I have always felt that consistently “taking responsibility” is about the only thing that sets adults apart from kids. Motivated by love, of course.)

Linklater’s films can be very “talkative,” and Boyhood is no exception. His actors are seekers of the meaning of life, and so–it would seem–is Linklater. His characters talk things out and ask soul-searching questions of each other, but if the film is philosophical, the philosophy is found in the small and ordinary.

Boyhood hums along so unpretentiously, so ordinarily that I was waiting for the “first” shoe to fall, let alone the second. There is one disturbing, violent family rupture a little ways into the 165 minute film, but that’s about it. It’s actually quite a calm film–something we’re just not used to in any era of filmmaking. No high drama, no dark overtones.

The film doesn’t skirt taking actual stabs at resolving the ultimate meaning of life, but the answer is tucked in everywhere in the film itself: love, “attachment.” We see exposed (as in our own lives) the motley web of family, friends, neighbors and co-workers who have our back and bless us on our way or catch us when we fall. But it is obviously the family where this all starts, with parents and their babies who grow up so darn fast. Although our protagonist is a boy, the parents are the real heroes–parents who actually parent: setting boundaries, disciplining, giving example, going the extra mile, encouraging, affirming and fighting for and with their kids, and each other.

For the most part, the parents actually give their kids great advice, except for the not one but two “Have Fun Kids, But Use a Condom!” speeches. This film–although it’s very pertinent to the years it is covering–has some heavy-handed anti-Bush, pro-Obama, anti-Iraq War messages, even going so far as to “cover up” the propaganda by poking fun at a kooky, Obama-Messiah worshipping woman.

The only way this film gets a pass on the blatancy is that the film is a kind of time capsule, marking such pop culture phenoms as the Harry Potter, Twilight and Lady Gaga juggernauts as well. Sadly, casual teenage sex (even besides the condom speeches) and drug use is no big deal in “Boyhood.” It’s just normal, part of growing up, fun. It’s certainly reality, but “Boyhood” gives it a smiling, benign stamp of approval.

Aside from these serious mars, Boyhood is fairly non-judgmental, standing to the side, calling ’em as it sees ’em.

Linklater is an unabashed music aficionado, and one gets the feeling that he’s promoting his favorite bands. The soundtrack is pointed, studied and obvious, the song lyrics repeating the exact emotion of the characters, verbatim.

The title “Boyhood” is a bit misleading if you are expecting a wild, breakaway, endearing “The Kings of Summer” type “boys are made of snips and snails and puppy dog tails” story. This is a boy squarely in his environment of inescapable big sisters, moves, chores, school and everybody telling you what to do.

Boyhood is definitely the story of blended families. It made me think of the upcoming Extraordinary Synod on the Family and World Meeting of Families, and how Pope Francis is urging the Church to be cognizant and solicitous of the ways today’s families are broken, but also how they glue themselves back together and find new configurations.

The end of the “snails and puppy dog tails” poem aptly describes “Boyhood’s” worldview:

What are all folks made of, made of?

What are all folks made of?

Fighting a spot and loving a lot,

That’s what all folks are made of.

–Robert Southey, 1820