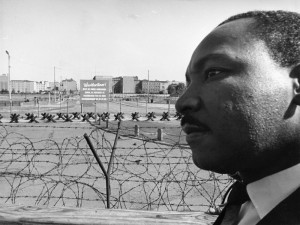

When we think of Martin Luther King Jr.’s great speeches, we don’t think of Berlin. And when we think of great American speeches in Berlin, we think of John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan; we don’t think of King. Yet, 50 years ago, the civil rights icon delivered historic remarks on both sides of the Berlin Wall.

Unlike the Kennedy and Reagan speeches, King’s appearances weren’t broadcast. And he offered no triumphant phrase comparable to “tear down this wall.” Perhaps that’s why his Berlin trip has been almost completely overlooked by even King admirers and Cold War scholars. But these remarks were dramatic, moving and deftly constructed — at a time of high tensions between East and West Berlin and between Eastern and Western powers. Fifty years on, they deserve another look, as an example of King preaching a U.S.-style civil rights message, but one adapted to German realities and to the constraints King himself faced.

On Sept. 13, 1964, King addressed 20,000 West Berliners attending an outdoor rally at Waldbühne stadium. Then he crossed the border at Checkpoint Charlie and delivered much the same speech — minus a few key passages — to 2,000 people packed into East Berlin’s Marienkirche. Why he was let through, without a passport no less, remains unclear.

East German authorities may have hoped that his appearance would be helpful to them ideologically. King had never been a vocal anti-communist, leading some to suspect that he was soft on communism and susceptible to being exploited or duped.

No doubt communist propagandists liked to exploit America’s dismal history of race relations. For the Soviet Union, this racism was ideal for arguing that democratic capitalism was in no way superior to communism; to the contrary, Moscow insisted, the American system was morally inferior. America’s racist past was an incessant drumbeat in publications from Pravda to (here at home) the Daily Worker. Figures like King and Angela Davis were celebrities in the communist press. By contrast, the communist world insisted that there was no racism in the U.S.S.R. Moscow absurdly portrayed itself as a racial utopia, unlike the racial hell in its Cold War counterpart.

“The African American in the United States was the oppressed figure, and this was to demonstrate the consistent evil of the West,” says Alcyone Scott, one of King’s translators on the Berlin trip. “They were pleased it was being exposed. That was their attitude. And that was the official position. .?.?. And when you have a civil rights movement pointing that out, they could naturally make propaganda hay out of it.”

And so King seemed to frame his Berlin remarks with an understanding of what he might be able to get away with and how he might be interpreted by his East German audience. He shied away from cataloguing the colossal injustices subjugating those east of the Iron Curtain. At the same time, he called out Berlin as “a symbol of the divisions of men on the face of the Earth” and repeatedly emphasized that reconciliation was God’s will. He made implicit comparisons between the suffering under segregation in America and the suffering in segregated Berlin. And he laid out a model for resistance and reform.

King began his speech by striking a bond with his German audience, noting that his parents had named him after the legendary German reformer. “I am happy to bring you greetings from your Christian brothers and sisters of West Berlin,” he started. “.?.?. Certainly I bring you greetings from your Christian brothers and sisters of the United States. In a real sense we are all one in Christ Jesus, for in Christ there is no East, no West, no North, no South.”

That introduction set the tone. The reverend had come to this church to give, first and foremost, a Christian message. It was, after all, a sermon. But there would be a political undercurrent to much of what he said.

King made two allusions to the wall, built just three years earlier. “For here on either side of the wall are God’s children, and no man-made barrier can obliterate that fact,” he said at one point. And then later: “Wherever reconciliation is taking place, wherever men are ‘breaking down the dividing walls of hostility’ which separate them from their brothers, there Christ continues to perform his ministry.” Here was affirmation of the inherent, God-given dignity of all human beings, regardless of whether communism denied that dignity, denied that God and denied free passage from East to West.

While King made an effort to distinguish “the struggle” in the United States from “your situation” in Berlin, he shifted back and forth between them in a way that made the parallels obvious. In one passage that must have had particular resonance among East Berliners, who were at a severe economic disadvantage compared with those on the other side of the wall, King acknowledged the fears among African Americans about not being able to hold their own in an integrated society. “Many have not had the opportunity to get an education, which will prepare them for the ‘promised land,’?” he said. “Many are hungry and physically undernourished as a result of the journey. Many bear on their souls the scars of bitterness and hatred, seared there by the crowded slum conditions, police brutality and .?.?. exploitation.”

King urged the need to overcome those fears. He talked about the potential power of grass-roots movements to instigate reform, introducing East Germans to names like Rosa Parks and places like Montgomery, Ala. He described how the American civil rights movement married the philosophy of Gandhi with the “Negro’s Christian tradition,” and he promoted “non-violence and love” as the basis for reform movements. This tactic of non-violence was probably the only approach that East Germans had available at the time.

Scott, the translator, said of King’s East German congregation: “Everybody in that place was totally enwrapped in someone whose story they knew and who represented the shame of America and its oppression, but who had the courage to resist and ask others, in their situations, also to resist. It was clear. It was the power of a message, and it was also couched in very clear Christian terminology.”

Actually, make that Judeo-Christian terminology. When King concluded his remarks, the church choir sang “Go Down, Moses,” which ends with the exhortation “Let my people go!” This “incredible performance,” as Scott remembered the rendition, was a capstone to King’s allusions to ancient Jews leaving the “Egypt of slavery” for the “wilderness” and ultimately the “promised land.” I cannot say whether King had a role in the selection of that hymn, but it was a beautifully fitting ending to a remarkable speech that somehow has slipped through the cracks of time.

[Editor’s note: this article first appeared in the Washington Post.]