Strange as it may seem at first, I find the key to the sanctity of Pope John Paul II in the closing words of an American novel published in 1988 — a book the Pope most likely never read. In brief, the heart of John Paul’s practice of “heroic charity” resides in the fact that he showed the world how to carry the cross.

Strange as it may seem at first, I find the key to the sanctity of Pope John Paul II in the closing words of an American novel published in 1988 — a book the Pope most likely never read. In brief, the heart of John Paul’s practice of “heroic charity” resides in the fact that he showed the world how to carry the cross.

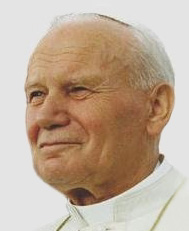

His May 1 beatification — the formal declaration that he’s “blessed” as a step on the way to recognition as a saint — is expected to be one of the biggest events Rome has seen in years. Those gathered in the heartland of Christianity, as well as the millions joyfully following the event around the world, will undoubtedly be celebrating the obvious greatness of this extraordinary man.

John Paul was human, and he made mistakes. He was slow to come to grip with the sex abuse problem, and not all his choices for bishop turned out well. But among the conspicuous elements of his greatness were his key role in the fall of communism, which he helped bring about by his powerful support for the Polish people’s deeply spiritual rebellion against their communist overlords; his remarkable body of encyclicals and other teaching documents positioning Catholics to engage contemporary secular culture; and his dramatic, globe-circling travels that captured the imaginations and moved the hearts of people throughout the world.

Important as all this was, however, to me the heart of his sanctity resides somewhere else. I find the idea expressed at the end of J.F. Powers’s second novel and last book, Wheat that Springeth Green.

Powers, a serious Catholic, was not a prolific writer—he published just three books of short stories and two novels—but he was a subtle and insightful one as well as a careful craftsman. Wheat that Springeth Green tells the story of an American priest named Joe, a would-be wearer of a hairshirt during his seminary years, who as a pastor in the post-Vatican II Church learns what everyday penitential suffering really means.

In an incident that recalls an episode in the life of St. John Vianney, patron saint of parish priests, Joe deserts his post and runs away. But, also like the Cure d’Ars, he soon relents and turns back.

Not long after that, friends give Father Joe a birthday party. After it’s over, he’s heading to his car when another priest, Lefty by name, calls after him about a chair he’s offered to give Joe and Joe has declined: “Sure you don’t want that chair?”

“Joe shook his head and kept going, calling back, ‘Yes,’ and when Dave called after him, ‘Where is it you’re stationed now — Holy…Faith?’ Joe shook his head and kept going, calling back, ‘Cross.’”

What does that have to do with John Paul II? Just this. In his declining years — old, sick, increasingly incapacitated by Parkinsonism — he soldiered on, demonstrating how a son of God accepts the Father’s will, takes up his cross, and goes to meet his death.

Other public men have hidden their weakness and disability — among American presidents, think of Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, and John Kennedy. Popes have sometimes done the same. John Paul handled it differently, carrying on his ministry as pastor of the universal Church as well as his failing strength allowed and allowing the world to witness his weakness in a display of uncommon heroism. No doubt there are many reasons why he deserves to be called “Blessed” and some day “Saint.” This one seems central to me.