Of Miracles and Mysteries

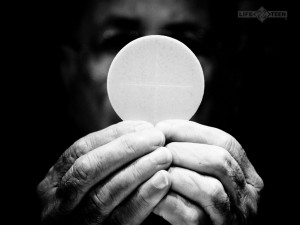

A little over 20 years ago, shortly after I had decided to enter the Church, I was being catechized by a very learned and wise priest (this was before the days of RCIA classes). As a physicist, I was struggling with the notion of transubstantiation — that by the action of a priest a wafer could be changed into the body and blood of Our Lord.

A little over 20 years ago, shortly after I had decided to enter the Church, I was being catechized by a very learned and wise priest (this was before the days of RCIA classes). As a physicist, I was struggling with the notion of transubstantiation — that by the action of a priest a wafer could be changed into the body and blood of Our Lord.

Our pastor first asked whether I believed in the resurrection; I said I did and he said that if I could believe in that miracle, why not in another one? He then told me that while one might occasionally have doubts or concerns about a particular Church teaching, one was, nevertheless, required to maintain any article of Dogma as being possible. (Fr. McA–forgive the faulty memory of an old man for phrasing this less elegantly than you did.)

Several weeks after this discussion, my doubts about the Real Presence were wiped away. During a 40 Hours procession the Monstrance was being carried in to the accompaniment of Tantum Ergo. I remembered enough of my high school Latin to translate the verses as they were sung, and as praestet fides supplementum sensuum defectui rang out, my heart filled, tears filled my eyes, and I knew without a doubt that the little cracker in that beautiful monstrance contained the body and blood, divinity and humanity, of Jesus Christ. Amazing Grace!

I was reminded that the Eucharist is a continuing miracle and a mystery after reading an article by Alicia Colon about a recent eucharistic miracle in Argentina: a consecrated host changed into human heart tissue, verified by witnesses and by pathological examination of the tissue and DNA (please go to the link for a more detailed account). There have been other Eucharistic miracles (see the Real Presence website) confirmed by the same rigorous process the Church uses to confirm miracles for canonization.

Since faith is at the root of our belief in the Real Presence, my point in this article is not to use such miracles as evidence, but to understand (in the spirit of St. Anselm — “faith seeking understanding”) what underlies the continuing miracle of transubstantiation.

In that spirit, to understand what faith had already confirmed, I delved into the works of St. Thomas Aquinas and later theologians, Edward Schillebeeckx and Karl Rahner. (Dear reader: please be patient–quantum mechanics will rear its ugly head later.)

To this philosophical novitiate, the concept of “substance” was murky; on the other hand, the term “accidents” — the physical attributes of a thing, as apprehended by the senses either directly or via instrumentation — was clearly defined. One could proceed all the way down to the properties — the “accidents” — of the sub-atomic constituents of the Host, quarks and all, and find they had not been altered by the act of Consecration. Then what would be the substance of the Host, before and after Consecration?

It occurred to me that “substance” just told us what a thing is, no matter what its appearance seemed to be, and that in the Consecration, transubstantiation corresponded to the change of the “real thing–substance” from bread to Jesus Christ.

To illustrate this notion for religion classes I gave to Catholic prisoners (nothing like a captive audience!), I used the following example: holding up a twenty dollar bill I asked the class if that bill was not issued by the government but by a counterfeiter with the same kinds of paper, ink, etc, would it still be a legitimate twenty? And of course, they all answered no. (I’ve come later to realize that this example comes dangerously close to the heretical notion of the Real Presence coming about through transignification–see the links above.)

How then does quantum mechanics relate to the Real Presence? This question didn’t enter my mind until I read a comment by Prof. Stephen Barr (a physicist whose opinions on science and the Catholic faith I greatly respect) refuting a Jesuit priest’s contention that modern physics has made Transubstantiation a meaningless notion.

As I interpret his article, Barr argued that what quantum mechanics told us about physical reality was irrelevant to the truth of transubstantiation (a metaphysical reality?):

In short, one can explain the doctrine of transubstantiation and distinguish it from other beliefs about the Eucharist without any use of the Aristotelian apparatus. I don’t know what quantum mechanics has to do with any of this. If anything, quantum mechanics makes a straightforward connection between what appears empirically and what is “really there” more obscure than it was in Newtonian physics, and to that extent would make it easier rather than harder to affirm the doctrine.

Before exploring this implied distinction between the knowledge of reality from science and from philosophy/theology, I’d like do a brief horsies-and-duckies discourse on quantum mechanics.*

First, quantum mechanics is itself a mystery: as the great physicist Richard Feynman remarked, “I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.” The theory gives probabilities for alternative results of experiments, probabilities that are confirmed to a high degree of accuracy (much like actuarial results — one may not know when any given person may die, but one does know that among a large number of 70 year old men, a well-defined percentage will die in the coming year).

Even though quantum mechanics is deterministic in a statistical sense, this probabilistic character bothers many physicists: Einstein himself opposed the probabilistic interpretation of quantum mechanics, insisting that “God does not play dice with the universe.”

Second, from the beginning of quantum mechanics scientists have posited a connection between the conscious mind and the role of the observer in determining quantum mechanical outcomes in experiments. As d’Espagnat puts it, “The doctrine that the world is made up of objects whose existence is independent of human consciousness turns out to be in conflict with quantum mechanics and with facts established by experiment.”

The conscious mind of the observer plays a role in making a choice of experiments and what is to be observed. One interpretation of quantum mechanics, proposed by John Wheeler and Raymond Chiao, has it that the observer creates reality by the act of choice in doing the experiment.

Since Chiao’s article on this in the collection of papers on the Vatican sponsored conference, “Quantum Mechanics–Scientific Perspectives on Divine Action” (Vatican Observatory Publications, 2001) is hard to access on the internet, I’ll quote from a Counterbalance review of the article:

He (Chiao) supports a “neo-Berkeleyan” point of view in which the free choices of observers lead to nonlocal correlations of properties of quantum systems in time as well as in space, giving Berkeley’s dictum, esse est percipi, temporal as well as spatial significance. Theologically he uses this generalized Berkeleyan point of view to depict God as the Observer of the universe. Here God creates the universe as a whole (ex nihilo) and every event in time (creatio continua). The quantum nonseparability of the universe is suggestive of the New Testament’s view of the unity of creation.

So, where does this lead us in understanding how quantum mechanics explains the Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist? I’m not sure. I reject those mystical interpretations of quantum mechanics exemplified in “What the Bleep” and other works entangling Eastern mysticism with quantum mechanics — whatever the truths of their insights into Buddhism or other Eastern religions, they have no clue as to what quantum mechanics is about.

On the other hand, as the French physicist/philosopher Bernard d’Espagnat has suggested, there is a “veiled reality” underlying the mysteries of quantum mechanics, a reality which suggests the existence of God. But because there is also a mystery in the Eucharist, it does not mean that this mystery, the Real Presence, is explained by a quantum mechanical veiled reality.

It may be that the perceived, yet unknown relation between consciousness and quantum mechanics is that which will enlighten us, tell us how the metaphysical reality of transubstantiation is totally confirmed in physical reality, a physical reality that the Patristic Fathers acknowledged but did not bother to explain.

To sum up, I’ll use my wife’s comment on this article: “Aquinas said that God is rational; what we don’t understand is not because it’s beyond reason, but beyond our rational capacity.“

*The best reference for a lay person on the quantum mechanical mystery is a fine book by Rosenblum and Kuttner, Quantum Enigma: Physics Encounters Consciousness.