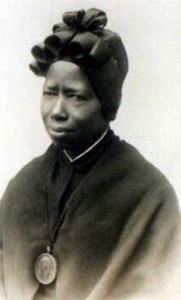

When Josephine Bakhita died in 1947, thousands of Italians passed her funeral bier to pay respects to a simple woman who had achieved great renown for her kindness. To this day, the people of Schio, Italy, honor now-Saint Josephine, a former African slave, with the title “Nostra Madre Moretta,” which means “Our Black Mother.”

When Josephine Bakhita died in 1947, thousands of Italians passed her funeral bier to pay respects to a simple woman who had achieved great renown for her kindness. To this day, the people of Schio, Italy, honor now-Saint Josephine, a former African slave, with the title “Nostra Madre Moretta,” which means “Our Black Mother.”

In her native land of Sudan, news of Josephine’s beatification was banned, yet Blessed John Paul II came to the capital city of Khartoum nine months later, despite the threats to his security, on Feb. 10, 1993. An immense crowd gathered in the Sudanese capital’s “Green Square” to hear the Pope and to honor this daughter of Africa. In his homily the Holy Father proclaimed:

“Rejoice, all of Africa! Bakhita has come back to you. The daughter of Sudan was sold into slavery … and yet was still free—free with the freedom of the saints.”

The path to sainthood for Bakhita could be accurately described as an odyssey. Growing up a happy child in a prosperous and locally important family, her idyllic childhood came to a sudden and violent end when she was captured by Arabic slave traders at the age of 9. In the years that followed, she was sold and resold several times before being brought to Italy by one of her owners.

Eventually Bakhita was placed in the care of some Canossian Sisters in Venice who prepared her for baptism. Years later, when her owner tried to take her back to Sudan, Bakhita refused and her case was brought to court. The Court ruled that since slavery was outlawed in Italy, she had never been a slave and she was allowed to remain in Italy.

Bakhita was baptized and confirmed on Jan. 9, 1890, and six years later she entered the novitiate of the Canossian Sisters who had helped to win her freedom. She did simple tasks and became well known for her kindness. When it became apparent that Bakhita had a great heart for the missions of Africa, her Superior asked her to visit convents to speak about her experiences, to prepare young sisters for missionary work in Africa, and raise funds for the missions.

Bakhita was baptized and confirmed on Jan. 9, 1890, and six years later she entered the novitiate of the Canossian Sisters who had helped to win her freedom. She did simple tasks and became well known for her kindness. When it became apparent that Bakhita had a great heart for the missions of Africa, her Superior asked her to visit convents to speak about her experiences, to prepare young sisters for missionary work in Africa, and raise funds for the missions.

The name given to her by her captors, Bakhita, means “fortunate.” St. Josephine was so traumatized by the cruelty she endured during her captivity that she forgot the name her family had given her. Recognizing the role of Providence in her newfound “fortune,” she took the name of Giuseppina Margherita Fortunata upon receiving the Sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation.

The stark irony in the name imposed by slave traders upon innocent young Bakhita sadly has a remarkable parallel today in the continent of her birth, as new traders come to Africa to impose a form of slavery under the misleading name of “reproductive health.”

Western population control organizations have targeted Africa for decades in an effort to stop African women from having children. While this agenda was rather crudely and explicitly stated when population control became official, although classified, U.S. policy four decades ago, since the mid-1990s advocates have been using the language of “reproductive health” to convince unsuspecting women that it is really in their best interest to stop having children. Euphemisms like “Safe Motherhood” laws and programs are routinely introduced, which promote abortion, contraception and sterilization.

All of this verbal engineering had been effectively resisted by life-loving Africans as they entered the new millennium, but the relentless, multi-billion dollar assault is starting to take its toll. In the summer of 2010, Kenya passed a bill that essentially opened the floodgates to legalized abortion, although Kenyans were told the opposite during a deluge of propaganda funded primarily by the Obama administration, which was found to have spent over 23 million dollars to influence the outcome. And in 2010, International Planned Parenthood Foundation, the largest abortion business in the world, announced a plan to increase abortions in Africa by 82% by the year 2015.

And how does this verbal engineering take root in the continent that still boasts the highest birthrates in the world? Consider the following excerpt of a press release, which promotes an upcoming “sensitization session” for African journalists:

“Twenty media practitioners from the print, electronic and online media will participate in the 8-10 March session being organized by the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, to sensitize the media on issues of sexual health and reproductive health. According to IPPF, the session will enhance the understanding of the participants, to be drawn from across sub-Saharan Africa, on sexual health and reproductive issues.”

In 2011, during his apostolic visit to Benin, which was historically one of the launching points for Christian missionaries in the 19th century, Pope Benedict XVI issued an Apostolic Exhortation titled Africae Munus. Within its discussion of the myriad opportunities and threats confronting modern Africa, the Pope commended the “courage of governments that have legislated against the culture of death – of which abortion is a dramatic expression – in favor of the culture of life.”

The Holy Father also mentioned other threats to human life in Africa such as drug and alcohol abuse, malaria, tuberculosis and AIDS. Further, he criticized AIDS prevention programs that are one-dimensional. The AIDS epidemic is primarily, according to the Pope, “an ethical problem. The change of behavior that it requires – for example, sexual abstinence, rejection of sexual promiscuity, fidelity within marriage – ultimately involves the question of integral development.”

Pope Benedict’s clarity on the issues of sexual ethics and integral human development does not come as a surprise to those who have closely followed his papacy, nor does his appreciation for Africa’s distinctive history and challenges. In his encyclical Spe Salvi, Pope Bendedict XVI holds out St. Josephine Bakhita as a model of hope not only for Africa, but for all of the Church, for “The example of a saint of our time can to some degree help us understand what it means to have a real encounter with this God for the first time.”

In the same encyclical, the Pope also recalls Psalm 23, which foretells Jesus as the Good Shepherd:

“The true shepherd is one who knows even the path that passes through the valley of death; one who walks with me even on the path of final solitude, where no one can accompany me, guiding me through: he himself has walked this path, he has descended into the kingdom of death, he has conquered death, and he has returned to accompany us now and to give us the certainty that, together with him, we can find a way through. The realization that there is One who even in death accompanies me, and with his ‘rod and his staff comforts me’, so that ‘I fear no evil’ (cf. Ps 23 [22]:4)—this was the new ‘hope’ that arose over the life of believers.”

“In Hope We Are Saved” is how the title of the Holy Father’s second encyclical is commonly translated, quoting St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans (8:24). The life of St. Josephine Bakhita reminds us of the ultimate triumph of hope over despair, of good over evil, of life over death. She reminds us that the Good Shepherd is always with us, leading us through our darkest moments, and that he will not abandon us should we get lost or discouraged. As we continue to work in the mission field of life in Africa and around the world, we ask for her intercession for her brothers and sisters who continue to strive for integral human development, and to live and build an authentic culture of life.

St. Josephine Bakhita, help us to not give into despair over the assaults of the forces of death arrayed against us. Help us win the battle against those who would exploit people for their own selfish purposes. Give us a heart for the missions like yours. Pray that we may defend life and the family today and work with your brothers and sisters to build a culture of life in your beloved Africa.

A version of this article originally appeared on Zenit.org.