Ah, winter has arrived in all its glory, which means one thing: more sledding bans!

Ah, winter has arrived in all its glory, which means one thing: more sledding bans!

According to The Associated Press, Dubuque, Iowa, has banned sledding at 48 of its 50 municipal parks. The reason: costly lawsuits.

In one case, a 5-year-old girl in Omaha, Neb., hit a tree while sledding and became paralyzed. In another case in Sioux City, Iowa, a man suffered a spinal cord injury after sledding into a sign. The first case resulted in a $2 million judgment, the second in a $2.75 million judgment.

To be sure, sledding comes with some risk. Newsweek cites statistics in a study by the Center for Injury Research and Policy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital — that sledding injuries send more than 20,000 kids to the hospital every year, of which 9 percent suffer traumatic brain injury.

On one hand, I can’t fault municipalities for banning an activity that may result in a sizable financial hit to their bottom line. At the same time, I lament the litigiousness and over-protectiveness that has become the hallmark of modern times.

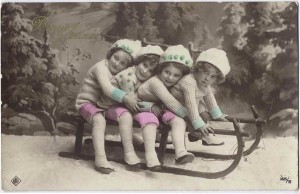

When I was a young lad in the ’70s, about a million kids hit the sledding slopes every time the snow fell. Unlike today, when you see two or three adults chaperoning every one kid, there wasn’t a single adult in sight.

About every 20 minutes, a kid would wipe out, tumbling round and round as mittens, ear muffs and boots came flying off. The kid would lie at the bottom of a hill, moaning, for a little while.

I certainly had my fair share of wipe-outs.

I had always been a Flexible Flyer type of fellow — I loved the superior steering control the thing gave me and it was safer than other nutty sledding devices, such as the aluminum saucer, which gave a kid zero control — but I used it so much, it eventually broke. I had to revert to a poor kid’s sledding device, the Mini-Boggan.

The Mini-Boggan was invented by a woman named Eunice Carlin, who apparently was trying to kill her children. Carlin was tired of her kids using their book bags to slide down snowy hills, so she worked with her next-door neighbor, a plastics executive, to produce it.

It was a thin, light, rectangular sheet that you laid on as you careened downhill at several hundred miles an hour, spinning uncontrollably until you collided with whatever you were inevitably going to collide with.

I made the mistake of riding a Mini-Boggan only once.

Unable to guide the thing, I slid off to the far right of our course, where one father had sawed down six pine trees to stumps.

My Mini-Boggan carried me over every one of them — six giant pistons that pounded into my ribs and stomach, knocking the wind out of me. I lay there in agony for several minutes before I was able to get up.

Needless to say, the risk and liability of the Mini-Boggan were the stuff of dreams for lawyers — which is why, thankfully, it is no longer made.

The regrettable truth is that there will always be risk in life. We can’t protect our kids from all of it without also preventing them from growing, exploring and discovering on their own.

So, what’s the solution? When towns ban sledding on park hills to reduce their risk exposure, look elsewhere. And be cautious when sledding anywhere. Wear a helmet. Invest in a good-quality sled, which gives you superior control. Chart your course to avoid dangerous paths.

And if somebody shows up with a Mini-Boggan, burn it!