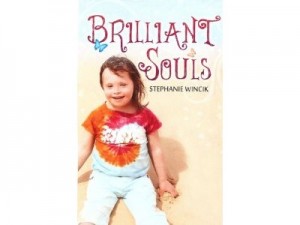

Stephanie Wincik is a registered nurse who doesn’t consider herself pro-life, or subscribe to any particular religious belief, yet after 25 years of working with the medically fragile disabled patients, she stumbled upon an article which galvanized her into writing a pro-life book, Making the Case for Life, which has in its enhanced second edition, become Brilliant Souls (One Horse Press).

Stephanie Wincik is a registered nurse who doesn’t consider herself pro-life, or subscribe to any particular religious belief, yet after 25 years of working with the medically fragile disabled patients, she stumbled upon an article which galvanized her into writing a pro-life book, Making the Case for Life, which has in its enhanced second edition, become Brilliant Souls (One Horse Press).

When Stephanie read in that article that 90% of unborn babies with Down syndrome are aborted, she was stunned, and researched further to discover that the norm among medical practitioners was to recommend abortion when an unborn baby is prenatally diagnosed with Down syndrome. She was compelled to discover why. “Unfortunately their advice was often base on fear, misinformation, or simply a lack of experience or familiarity with intellectual disabilities.” And “the parents’ decision was largely based on having no prior experience with people with disabilities as well as a lack of confidence in their own ability to parent a disabled child.”

The reason for her book is to debunk the most popular myths which underlie the decision to abort unborn children with Down syndrome, which she does to great effect, using logic, statistics, and her extensive experience with the disabled. Not only does she prove that such individuals present as many benefits as they do burdens to society but she forces the reader to question some of society’s values. Who is of greater use to society, a rich person who is unhappy or a disabled person who cannot hold a job but spreads joy wherever he goes? Is it too much burden to pay for the cost of the extra medical care an innocent individual with Down syndrome needs versus that of a drug addict or criminal, whose care we readily provide? She questions assumptions about what constitutes a happy childhood by asking if raising children who expect life to be without challenges and are thus unable to give of themselves is a good idea. And the most challenging of all, what if the attitude of those with Down syndrome is superior to our own, providing the world the humanity it is lacking?

Wincik interviews speaker and advocate Bridget Brown, a young woman with Down syndrome whose letter comparing the abortion of babies with Down syndrome to Hitler’s death camps to the Washington Post thrust her into the spotlight and whose group “Butterflies for Change” challenges that rejection of those with Down syndrome. Wincik describes how a little girl named Chloe Kondrich has touched thousands of hearts with her father, Early Intervention Specialist and advocate Kurt Kondrich, and met such luminaries as Governor Sarah Palin and Pittsburgh Pirate Andy LaRoche. It inspires the reader to go out and make the world a more welcoming place for babies with Down syndrome.

Dennis McGuire, PhD challenges the reader to rethink assumptions about the place of people with Down syndrome in society by his essay, entitled, “What Would Happen if People with Down Syndrome Ruled the World?”

Brilliant Souls is a compelling read, challenging in its content and uplifting, especially if you are fortunate enough to know someone with genetic diversity. A caution to Catholic readers: Ms. Wincik’s unorthodox spirituality is evident when she asserts that individuals with Down syndrome communicate with the dead and may be reincarnated. I agree that my seven-year-old daughter Christina expressed startling awareness of the presence of Christ despite very limited ability to communicate and that I have heard such accounts from other parents, yet we must discern such experiences within the wisdom of Church teaching. Still, Ms. Wincik’s insights into society’s perception of disabled individuals is an important and penetrating read, and may move a person who does not come from a particularly strong moral tradition. Share it with someone in the medical profession and open a heart.