“Am I creating wealth, or am I engaging in rent-seeking behavior?” If this question would be asked during a course of business ethics at George Mason University (GMU), few would be surprised. “Rent-seeking” is a term used often in “Public Choice” economics, and GMU has been the home of an academic center with that focus. The question, however, also appears in one of the most relevant publications released by the Vatican. That indeed is a surprise.

GMU had the late Nobel Laureate James Buchanan and still has Gordon Tullock on its faculty, two great pioneers of the discipline. In 1967 Tullock wrote “The Welfare Costs of Tariffs, Monopolies, and Theft” and later, in 1974, Anne Krueger (the former chief economist of the World Bank) coined the word “rent-seeking.” As “rents” can be legitimate, I prefer to use “privilege seeking.”

Allow me to turn back the clock to three decades ago, when I received a surprising call. The Argentine Ambassador to the Vatican, Santiago de Estrada, who did not share my hardcore free-market views, asked me if I could visit with him. He was back in Buenos Aires for a short visit. As a young professor, and one of the few classical liberal professors at the Catholic University, I had started writing about the need for the Church to develop a new understanding of free enterprise.

Ambassador Estrada shared my concern. If I recall correctly, this is what he said: “I have been at meetings of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. There is a sense of inefficacy; the economic teachings sometimes focus on aspirations, worthy goals, but seldom offer something more.” His legitimate concern was not the rich anthropology taught through the centuries by Christian churches, but the effort to give guidance to business and economic leaders. The aforementioned Council is in charge of that task and the one which released the document mentioning rent seeking.

It takes time for Catholic doctrine to incorporate evolving economic consensus. In 1987, John Paul II, at a major speech at ECLAC, the Latin American economic think tank of the United Nations, spoke in favor of private enterprise: “The challenge of poverty is so great that in order to overcome it, we must make the greatest possible use of private enterprise, with its potential effectiveness, its capacity to use resources efficiently, and the abundance of its energies for renewal.”

Years later, in John Paul II’s encyclical Centesimus Annus, the Church endorsed the concept of a free economy under a rule of law. In point 42 of that document the Pope wrote that: “If by ‘capitalism’ is meant an economic system which recognizes the fundamental and positive role of business, the market, private property and the resulting responsibility for the means of production, as well as free human creativity in the economic sector, then the answer is certainly in the affirmative, even though it would perhaps be more appropriate to speak of a ‘business economy,’ ‘market economy’ or simply ‘free economy.’”

On other occasions, John Paul II spoke very highly of the role which entrepreneurs play in society: “[T]he degree of well-being that society enjoys today would have been impossible without the dynamic figure of the entrepreneur, whose function consists in organizing human labor and the means of production in order to produce goods and services. Without any doubt, your task is the first order for society.”

Today, most of the topics dealing with economics and free enterprise are handled by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. Its work is conducted in consultation with experts from different social disciplines. It organizes seminars and releases different documents. Publications from the Catholic Church have different degrees of authority, and—in this new era—statements range from encyclicals to Twitter postings.

The Pontifical Council has been releasing “Notes” and “Reflections.” One year ago, it released a 30-page booklet, “Vocation of the Business Leader: a Reflection.” No other document from the Vatican has focused so much on the role of business leaders and entrepreneurs. It is intended “to be an educational aid that speaks of the ‘vocation’ of the business men and women who act in broad and diverse business institutions.”

In this booklet, the Council acknowledges the legitimate role “of profit as an indicator that a business is functioning well. When a firm makes a profit, it generally means that the factors of production have been properly employed and corresponding human needs have been duly satisfied. A profitable business, by creating wealth and promoting prosperity, helps individuals excel and realize the common good of a society.” The document recognizes the existence of crony capitalism and corruption and regards them as violations of principled entrepreneurship. It continues the tradition that sees businesses, in the language of John Paul II, as legitimate expressions of freedom. “Business leaders have a special role to play in the unfolding of creation—they not only provide goods and services and constantly improve them through innovating and harnessing science and technology, but they also help to shape organisations [sic]which will extend this work into the future.”

The Vatican is not and should not be a center for the promotion of concrete free-market or interventionist solutions. The Church does not have “technical solutions to offer or models to present” — that is the role of lay persons. For those of us who favor a “free economy,” it helps to have outstanding economists, such as Nobel Laureate Gary Becker, as a member of the Pontifical Academy of Science. But economists of different persuasion are also part of the debate and influencing publications.

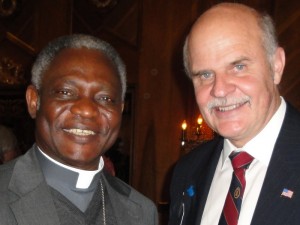

Cardinal Turkson, from Ghana, is the current head of the Council. It has Flaminia Giovanelli, in one of its leadership positions. She is one of the highest lay persons in the Vatican. Another one is Harvard University Professor Mary Ann Glendon, the first female president of the Pontifical Council of Social Science. Cardinal Turkson is familiar with the think-tank world, such as the efforts of the Institute of Economic Affairs in Ghana. Prof. Glendon knows the U.S. scene well. With the likelihood that Pope Francis will use his many pastoral charismas beyond the walls of the Vatican, I expect that each Pontifical Council, many working as think tanks and educational centers, will rise in profile. Pope Francis will take care of the faith. The economic views that come from Vatican documents will depend more and more on a fruitful dialogue between those of us in the laity, both Catholic and non-Catholics like Gary Becker, and the leadership team of each Council.

[Editor’s note: a version of this article first appeared at forbes.com.]