Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

It’s a bit disenchanting to suppose that the Christian revolution of the fourth century originated in just another contest between ambitious pagan rulers. But was that really the case?

It’s a bit disenchanting to suppose that the Christian revolution of the fourth century originated in just another contest between ambitious pagan rulers. But was that really the case?

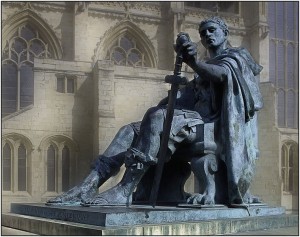

Today, many historians tend to think so. They follow Eusebius (Vita Constantini 1.27) the fourth century Roman citizen and bishop who linked Constantine’s religious conversion to his distress during the high risk campaign to conquer the city of Rome, i.e. his invasion of Italy in AD 312. With the civil war already underway, Constantine is said to have opened his soul in an appeal to the highest God, the Deus Summus, following which he saw in the sky his famous vision, including the instruction, “in this sign conquer.” Whereupon he had a Christian symbol, the chi-rho, embossed on the shields of his soldiers, who then continued on to victory.

With regard to his religious conversion, other scholars speak of an evolution on Constantine’s part. Whereas the pagan historian, Zosimus, who lived almost two centuries after Constantine, sought to cast the Emperor’s conversion in an ignoble light, associating it with the execution of Crispus in 326.

The upshot of the above theories is that Constantine’s military victory redounded to the benefit of Christians without our ancestors having earned it — I mean earning it in the same sense that the Macabees won the Jewish insurrection against the Greek occupation, or the Patriots won the American Revolution.

The implication is that the Christian Revolution began as a secular coup d’état, to which our ancestors in the faith contributed mainly prayers. Sending flares up to heaven is, to be sure, a worthy contribution. But years later the praying is not so prone to excite celebration as, say, the Cristero Rebellion depicted in the film, For Greater Glory. Probably not so electrifying would be a movie about novenas offered for relief from Diocletian’s policy of persecution.[1]

As Christians desiring to celebrate Constantine’s Edict of Milan and the Christian liberation, we can gain enthusiasm, I suppose, from the comparison with King Cyrus of Persia who defeated Babylon militarily. Cyrus, the Gentile, freed the Jewish people to return to Jerusalem (538, BC), just as Constantine, the alleged religious syncretist, freed the Christian people to practice their religion.

The late Professor of antiquities, Thomas G. Elliott, takes a revisionist view that might be more inspirational. Based on his rereading of the original sources, Elliott argues that from the beginning it was a fight to promote religious freedom for the Gospel. Diocletian’s edict of 303 was the provocation. The Great Persecution traumatized the hearts and radicalized the minds of people like St. Helena, her son Constantine, and intellectuals like Lactantius. If Elliott is right, then Christian thinking in the 4th century helped instigate the secular coup d’état. The Christian Revolution under Constantine sprang from Christian roots.

That Christian ideology was at the root of the revolt is evidenced in Constantine’s own words. Twelve years after taking Italy, Constantine fought his third civil war, defeating the “mad” pagan Emperor of the East, Licinius, his last rival for the throne. With control of the entire Empire now secure, Constantine was able to speak more openly about religion. Forthwith, he wrote to the pagans of the East (letter of Autumn 324), that his Christianizing mission had begun in the west “at the remote Britannic Ocean.” Elliott thinks this “has to refer” to Constantine’s reign in Britain beginning in 306.

Several weeks after the aforesaid letter Constantine wrote that sometime before his invasion of Italy he had been planning, “with the secret eye of thought,” to end the persecutions militarily and impose a religious revolution for the spiritual betterment of the Empire.[2]

None of the aforesaid scenarios are all that satisfying, however, given that we have no firm or detailed information about the politics of the young Prince before 306; nor about the state of his theological views prior to his vision in the sky. It is not impossible that his political plans germinated early in the Summer of 305, with discussions around the campfires during his 1600 mile flight to Constantius.

The leading expert here, Charles Odahl, does place Constantine in the pagan camp prior to his chi-rho vision, based largely on the contemporary architecture, sculptures, and coins minted in Constantine’s western realm between 306 and 312.[3] But not so fast: Initially a junior member of the Tetrarchy, Constantine (assuming he were already favorable to Christianity) would have been disinclined to tip his hand by minting coins that telegraphed revolutionary religious intentions. Remember that all his fellow tetrarchs were hostile to the Gospel.

Another reason why official insignia might mislead us about Constantine’s religious beliefs before 312 is that they were part of the Tetrarchy’s campaign for cultural revival along pagan lines. The old coins & etc. were designed to honor traditions which had for some time been fading in popularity. Accordingly, the official policy of the Tetrarchy was to renew allegiance to the Olympian deities in order “to restore cultural unity to Roman society.”[4] Constantine may have bided his time and practiced “numismatic diplomacy” until his opportunity came.[5]

Seventeen centuries from now, historians studying 21st century America for the first time might look at freshly minted coins in 2012, or US postage stamps featuring a nativity scene. Their initial hypothesis might portray the USA as a pious nation trusting in Almighty God and encouraging Judeo-Christian ways. But this conclusion would have to be revised radically as soon as written records were unearthed. Newspapers and magazines would show that the U.S. Government was militantly secular in 2012; that it discouraged religion in the public square, especially in schools. In the moral sphere, public policy promoted abortion, sodomy and pornography at home and abroad.

But Rome in 312 had no newspapers or magazines. Extant written works reflect the point of view of an upper class prominent enough to get their writings distributed and copied for posterity. Therefore, as we examine that fateful year that changed the course of history via three major battles – Turin, Verona, and the Mulvian Bridge outside Rome — we see mysterious and confusing antecedents. Historical scholarship taken as a whole gives us a puzzling picture as to where the leading actor, Constantine, was coming from spiritually. In short, we are left in a state of mystification and uncertainty as to the origins of what we celebrate this year – the most important political revolution in the history of the human race.

…in spite of the loud assertions of certainty, we are left in the end with the conjectures of individuals as to the inner life of another individual dead these sixteen hundred years.[6]

But we do, happily, know something about the way God works. It is usually through men in cooperation, not supermen acting autonomously, that the Great Helmsman of history steers events. Yes, superlative leaders are vital, but so are their followers. How effective is the head of the spear without the shaft? It was not just George Washington and his continental army, but all 55 signers of the Declaration of Independence, who inspired the document’s composition, and who put their lives, fortunes and sacred honor at risk.

Not even Jesus himself spread the Gospel exclusively by his own efforts. In fact he never traveled beyond Israel, and left it to his disciples to spread the Good News throughout the Roman Empire and the entire world.

It is now the 1700th year since the Christian revolution under Constantine got underway with a vengeance. And so, employing speculation informed by the tendencies of human nature, and taking into account historical manifestations of divine Providence, let us try to peek a little deeper into the genesis of this grand event.

______

I submit that the revolution was not all Constantine’s idea. A lot of the credit should go to less prominent Christians, many of them now nameless, who exhibited varying degrees of devotion and/or submission to Church authorities. The Catholics backing Constantine were people in diverse spiritual conditions with disparately formed consciences.

Today is no different. A recent Pew Research study found that on social issues like abortion and gay rights, 37% of practicing Catholics nationwide thought President Obama better reflected their views than did Mitt Romney; whereas 54% of the weekly attendees at Sunday Mass went with Romney on the social issues. This 10 to 7 ratio shows no consensus among churchgoing Catholic laymen on how to relate faith to citizenship.

It seems there was no consensus in the 3rd and 4th century either, as indicated by the dissension that surfaced as soon as the persecution ceased. Immediately, the Arian heresy reared its ugly head. So too the Donatist schism. The notion is, therefore, nonsense that Christian thinking under persecution was as uniform as indicated in the pertinent writings that have survived since antiquity. Christians must have entertained a great variety of more or less obscure ideas on how to deal with a government hell-bent on exterminating them.

We know, most illustriously, that some persecuted Christians resisted the pagan edicts and became martyrs. Infamously, others were scorned as traditores for caving in to the government and submitting to decrees requiring citizens to engage in idolatrous ritual sacrifices. Many Americans would do the same today if a new Diocletian were to impose a bloody persecution. Indeed under the pressure of politically correct norms, postmodern traditores abound, propelled by today’s media into greater prominence than accrued to the Christian renegades of antiquity.

Among the Roman traditores, some repented of their failure under pressure. Repentance counts for a lot, and some of the contrite “traitors” must have been taken aback by rigorous terms for full reintegration into the community of Christian believers.[7] If subjected to exclusions or penances they considered excessive or unfair, Christians short on docility felt, no doubt, a measure of resentment toward the Church.

Having to witness unspeakable horrors, some of the laity must have resented clerically imposed penalties with an intensity proportionate to the persecution to which they succumbed. Some of the more resentful traditores reacted, no doubt, by discounting other clerical guidelines, quite possibly including cautions or mandates against resorting to violence.[8] In fact it is debatable whether the 3rd and 4th century hierarchy was theologically justified for imposing any such limitation on laymen acting politically as citizens.[9]

Laymen in such a situation may have twice set fire to the imperial palace in Nicomedia, right under the noses of Diocletian and Galerius.[10] Others may have joined militant bands of insurgents, the “bagaudae.” If and to what extent they did so is impossible to know today, given the paucity of relevant ancient sources that survive. But it does appear that during the Third Century the Gallic bagaudae managed to win some short-term military victories.

Eusebius records the first hand account by St. Dionysius, bishop of Alexandria, describing his liberation from detention during the persecution of Decius (mid-3rd century). His rescue was the spontaneous work of attendees at an Egyptian wedding. Upon hearing that the bishop had been arrested and held in custody nearby; the guests rose, forcibly dispersed Dionysius’ military guard, and then compelled the bishop to flee rather than embrace martyrdom.

But spontaneous, bottom-up revolts rarely develop into successful revolutions unless combined with a top-down revolutionary effort.[11] The Rebellion of Spartacus (73-71 B.C.) boasted as many as 70,000 fighting men, more than the bagaudae ever mustered; more in fact than Constantine commanded at the Mulvian Bridge. But Spartacus lacked assistance from the upper strata of society, and so his forces were finally cornered and crushed by the Roman legions.

By contrast the Christian Revolution succeeded because the forces under Constantine were mobilized and organized at the top, were brilliantly led, and were willing to fight fiercely against the forces in the other three-fourths of the Tetrarchy. And superintending this equation was the interposition of divine Providence.

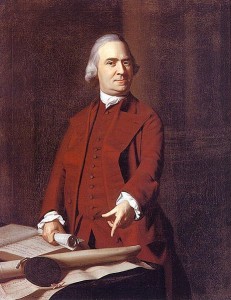

In 312, Christian soldiers within Constantine’s forces may have been comparatively few in number. In society at large Christians comprised about ten percent of the Empire’s population. But as Sam Adams, famed leader of the American Revolution said, “it does not take a majority to prevail, but rather an irate, tireless minority, keen on setting brush fires of freedom in the minds of men.”

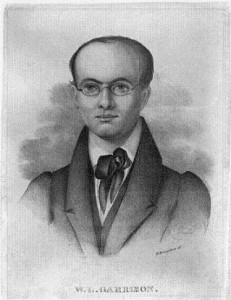

In the 19th century the abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, an anti-slavery periodical founded in 1831, was still below 400 in weekly circulation after almost two years of publication. Its founder, William Lloyd Garrison, insisted rightly that “the success of any great moral enterprise does not depend upon numbers.”

It may well be that a small minority from within the ranks of Christian intellectuals and propagandists (complemented perhaps by persuasive Christian officers in the emperor’s military retinue) kindled a spark in Constantius’ and/or Constantine’s thinking which ignited the ideological flame that inspired the war of liberation in 312. Any such crusaders wielding the sword of the Spirit in the imperial court (as per Ephesians 6:17, rather than swords of Roman steel), would have exerted a disproportionate impact in the political sphere relative to any political influence proceeding from the rest of the Church. In the 3rd century the majority of Churchmen were pacifists, but the minority could have carried the day within the highly militarized circles surrounding Constantine at Trier, his capitol since 306, or even at Nicomedia earlier.

Christian pacifism then took various forms. Many who resigned themselves to the inevitability of persecution in the short run still hoped somehow to escape the government’s notice, even as they risked attending secret masses in private homes. Some of the more eschatologically minded waited fatalistically for the final end, thinking their plight to be intertwined with the looming end of the world. Others, however, had less hope in an impending Rapture, and so they fled with their families to the Goths. By emigrating they helped spread the Gospel beyond the borders of the Empire.[12]

But more importantly for our purposes was the minority within a minority — the activists — Christian Romans on alert for a favorable opportunity to make the world safer (morally and physically) for their children. They must have looked for a slit or tear in the overarching pagan oppression. The more politically astute must have strategized on how to rip and expand the rift into a Christian revolution. They knew it might have taken place already if two of the friendly Emperors had exercised power more assertively and for a longer duration; or if 3rd century Christians had been better prepared to take advantage of political breaks in their favor.

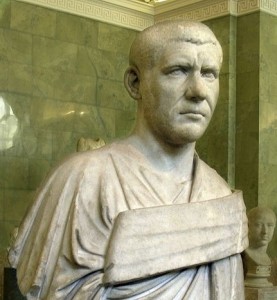

The tragic assassination of the Christian convert, Emperor Alexander Severus (222-235), had terminated the first really hopeful reign. Shortly afterwards, another hope had arisen in Philip the Arab, Emperor from 244-249, who converted to Christianity along with his wife, Severa. But he too died by the sword in a civil war against rebellious legions under the general, Decius. In a sign of those barbarous times, the Praetorian Guard murdered Philip’s eleven year old son and political heir, Philip the Younger. Then, going from bad to worse, the ousted imperial family’s affinity to Christianity was, “in some measure,” Decius’ motivation in renewing persecution on an Empire-wide scale.[13]

In the half-century after Alexander Severus — the era of the Barracks Emperors, 235-284 — the imperial government saw some twenty Emperors rise and fall, as well as various pretenders and local rulers. Events glaringly demonstrated the dysfunctional nature of a political system in which the main way to overthrow an autocrat was by assassination and/or by civil war.[14]

In such an unstable environment, some Christians must have perceived that radical change might be possible. Biding their time, they awaited another leader like Severus or Philip, who might, under God’s guidance, survive the political tumult. This kind of subversive thinking may well have reached young Constantine’s ear.

But unlike the Persian monarch who listened sympathetically to Esther during the fifth century, B.C., Constantine did, or eventually did, convert to his solicitor’s religion. One possible councilor was the Christian rhetorician, Lactantius, who would later tutor Constantine’s eldest son, Crispus. This Christian tutor worked in high imperial circles before the Great Persecution and young Constantine “probably was sitting in on some of the lectures of Lactantius at Nicomedia in the period (293-305).”[15]

Constantine was intelligent and ideologically curious. Well before 312 he not only encountered, but seems to have entertained, seditious ideas suggesting that a champion might change the Roman “constitution” (such as it was), and secure tolerance and/or primacy for Christianity.

Likewise, the American Civil War originated long before the firing at Fr. Sumter in ideological warfare, conducted by abolitionist agitators like Garrison, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Composed by Stowe in 1852, her novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, helped set the stage for the war to emancipate the slaves. A decade later, upon meeting Abraham Lincoln, the President is said to have exclaimed, “so you’re the little woman who started this big war!”

Similarly, the war of liberation conducted by Constantine did not originate when his legions began their march early in 312, but rather in the ideas and conceptual forces that antedated the military campaign. As the biographer, Henry James, put it in 1930, “ideas are, in truth, forces.”

When the Great Persecution commenced in earnest, A.D. 303, many Christians looked hopefully, even desperately, to Constantius (Constantine’s father), the tolerant tetrarch of three jurisdictions in Gaulia and Britannia. Christian political thinkers throughout the Roman Empire must have discussed plans for a revolution, even agitated for one, within the limits of what the pagan constitution allowed, i.e. using well precedented military/political means to transform the imperial government into a favorable autocracy. The key would have been to bring Rome itself – and not just Constantius’ domains in the northwest – under his lasting sway.

But two years into the Great Persecution, Constantius was suffering from poor health and advanced years; while his eldest son, Constantine, had yet to attempt his long ride to freedom from his position as “virtual hostage” at the imperial court in Asia Minor. Given that political change was accomplished so lawlessly and erratically, Christians desirous of improving the constitution (if “constitution” it can be called) faced a daunting task. But the times were not without possibilities if Christians could recruit, convince, or otherwise persuade a leading military man to spearhead the revolution.

Contrasting our present situation in the United States today, we can more easily conceive political aims, and more peaceful means, insofar as the US Constitution is a written document, quite unlike imperial Rome’s. Most notably the fifth Article in our Constitution demarcates non-violent means for citizen democracy, including An Article V Convention for proposing Amendments. Such a Constitutional Convention has often been attempted, but so far never convened. Earlier this year it was proposed by retired five-term Congressman, Tom Tancredo.

Alas for the Romans, given the primitive constitution they had to work with, no comparable option was conceivable. And yet in every circumstance, including the unfavorable situation posed by Roman politics, there arises the optimism immortalized by Alexander Pope: “Hope springs eternal in the human breast.” Consider Ireland, occupied for centuries under the British. The Irish undertook one failed insurrection after another. Finally, after generations of political disappointments, success came in the Irish Revolution of 1919-1921.

Similarly, Orthodox Russians prayed and waited for seven decades after the “Whites” failed to overthrow the Bolsheviks or “Reds” in the Civil War of 1918-1920. Halleluiah, the blessed deliverance of Christmas Day, 1991, brought the demolition of the Soviet Union. Ronald Reagan, Pope John Paul, and Boris Yeltsin lived to see their inspired dreams come true of bringing down the “evil empire.”

As for the Christians in ancient Rome, afflicted by persecution, we might speculate on a range of prayers offered with varying degrees of hope during the seven decades from Emperor Alexander Severus’ assassination until Constantine’s accession to the tetrarchy. From 235 to 306 AD, petitions sent up to heaven may well have included these:

- Lord, take me home without delay.

- Oh blessed Savior help me embrace the cross of persecution, that I might imitate your own docile and lamb-like submission to crucifixion.

- Please, Lord, protect me and my family. From the persecutors, hide us in the shadow of your wings. Guide us safely toward refuge in the Gothic lands.

- Lord, please raise up for us another imperial protector, like Alexander Severus and his mother, Julia Mamaea, or like Philip the Arab and his wife, Severa.

- St. Michael the Archangel defend in battle our brethren who defy, disrupt, or actively resist the oppressor.

- Please, Lord, give us the wisdom of serpents in learning from our history and in dealing with our political oppressors. Help us temper zeal with prudence lest we bring worse persecutions down upon our heads.

- Lord show us how to “fight the good fight.” Help us “drive the dragon from the administration of public affairs.”[16] Teach us ways whereby to defeat the pride of the pagan, and submit the imperial throne to the service of the altar.

Christians back then were a various and sundry people, and so we remain. We have divergent ways of praying, and of expressing hope. Many were the inconsistencies then (as today) among confreres in submitting to ecclesiastical authority. Yet despite lack of consensus on how to deal with political oppression, our spiritual forebears’ hopes were realized during the 2nd half of Constantine’s lifetime in ways that must have seemed like a pipe dream to the practical minded.

Similarly centuries later when, miraculously, the continental army defeated the mighty British Empire: divine Providence intervened. In 18th century America as in 4th century Rome, the good Lord favored our cause – “Annuit Coeptis.”

Endnotes

[1] Digression on celebration: The Annunciation (announcing the virgin conception of Jesus) is celebrated on March 25th. This beautiful feast day is, however, subordinate to the solemnity of Holy Week. Next year, in fact, it will be moved to April to make way for Holy Week of 2013, which supersedes any other feast in March. The virgin birth was pure gift from God, with the exception of Mary’s fiat; whereas Holy Week celebrates an heroic fight by Christ in his capacity as both God and man, culminating in his victory over death on Easter Sunday. Thus, Holy Week is the greater celebration.

[2] Eusebius, Life of Constantine 2.28; T.G. Elliott, The Christianity of Constantine the Great (Scranton PA: The University of Scranton Press, 1996), pp. 45-47.

[3] Charles Odahl, Constantine and the Christian Empire (New York: Routledge, 2004), p. 94-95. Email to RS dated 8/1/2012: Constantine “had not become a Christian until 312 — he was worshiping as a pagan and building pagan temples all over Gaul (templa pulcherissima) on the Italian campaign and with what he believed was a personal revelation from God.”

[4] Odahl, ibid., p. 56; Elliott, supra, p. 23 contends that propaganda promulgated by rulers (coins and panegyrics) says “nothing whatsoever about their personal religious belief.”

[5] Odahl, ibid., p. 90.

[6] Alfred A. Bellinger, “The Age of Constantine: Tradition and Innovation. Report on the Dumbarton Oaks Symposium of 1966,” in Dumbarton Oaks Papers, no. 21 (Washington, D.C.: Center for Byzantine Studies for Harvard Univ., 1967), p. 287. Hereafter cited Dumbarton Oaks Papers.

[7] Elliott, supra., p. 214, postulates that Constantine delayed his Baptism until AD 337, not in order to delay the Sacrament’s cleansing power against sins until the last possible moment, but rather because being baptized earlier would have required that he incur clerically imposed penances deemed impolitic in terms of the stability of his regime. (One thinks, however, of King Henry II in 1174 running a gauntlet of 80 monks striking him with rods).

[8] Arguably all the preconditions for armed insurrection, as would later be delineated in just war doctrine, and in paragraph 2243 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, had been met by the time Constantine succeeded his father, Constantius. In hindsight, and applying retroactively another latter-day doctrine [the preeminence of the laity in political affairs (see below, next endnote)]we might say that the early 4th century Church overstepped its bounds by setting parameters for laymen acting politically against despotic imperial persecutors like Diocletian.

After Constantine dispersed the persecutors and emerged as sole Emperor, and also as the chief authority within the laity, this imperial layman even went so far as to declare himself the equivalent of a bishop in mediating interaction between the sacred and secular spheres of Roman society: Johannes A. Straub, “Constantine as Koinos Episkopos: Tradition and Innovation in the Representation of the First Christian Emperor’s Majesty,” in Dumbarton Oaks Papers, p. 51.

[9] John-Paul II, Sollicitudo Rei Socialis 47 (1987): “It is appropriate to emphasize the preeminent role that belongs to the laity, both men and women, as was reaffirmed in the recent Assembly of the Synod. It is their task to animate temporal realities with Christian commitment, by which they show that they are witnesses and agents of peace and justice.” (Emphasis mine)

[10] Unwilling to believe that real Christians could resort to such tactics, Constantine’s advisor, Lactantius, explained the arson as a false flag operation designed to blame the Christians. He claimed the plot was concocted by Galerius, much like Nero burning Rome in the 1st century, or like Hitler burning the Reichstag in the 20th. Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum 14.

[11] On the violent rescue of Dionysius see Eusebius, Historia Ecclesia 6.40. On “combined seizure” of power see, Feliks Gross, The Seizure of Political Power in a Century of Revolutions (New York: Philosophical Library, 1958), pp. 52-53, 114-117.

[12] Santo Mazarino, The End of the Ancient World, (NY: Alfred A Knopf, 1966), pp. 46-47.

[13] Massey H. Shepherd, Jr., “Liturgical expressions of the Constantinian Triumph,” in Dumbarton Oaks Papers, no. 21, p. 65 — citing Eusebius, Historia Ecclesia 6.39.

[14]Chester G. Starr, A History of the Ancient World (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1983), p. 660.

[15] Odahl, supra, 9, 54, 56, 125, and email to RS dated 8/4/2012; Charles Odahl, “Constantine the Great and Christian Imperial Theocracy,” Connections: European Studies Annual Review 3 (2007): 91

[16] So phrased later by Constantine, 324; Odahl, Constantine and the Christian Empire, p. 186, quoting Eusebius’ copy of the imperial missive of 324; Eusebius, Life of Constantine 2.46.