“At once, the Spirit drove him into the wilderness, and he remained in the desert for forty days, tempted by Satan. He was among wild beasts, and angels ministered to him” (Mark 1:12-13).

“At once, the Spirit drove him into the wilderness, and he remained in the desert for forty days, tempted by Satan. He was among wild beasts, and angels ministered to him” (Mark 1:12-13).

These are the words written by Saint Mark that begin the story of Jesus’s works following his baptism in the Jordan River by John the Baptist (Mark 1:9-11). Forty days is a significant number, spiritually if not numerically, and it’s doubtful that the Spirit was a slave to the clock and calendar as we are today. Those forty days that Jesus spent in the wilderness were a special and focused time spent in solitude to prepare for his ministry. He was following the Old Testament traditional purification period. Israel wandered in the desert for forty years (Numbers 10—22) to be purified and receive its promised inheritance. Moses spent forty days and forty nights fasting and in prayer atop Mount Sinai as he received the Law. Elijah hiked to Mount Horeb to resign his commission as a prophet only to hear the voice of God so still as a whisper amid the natural disaster of a mountain tumbling down. And Jesus, who sets the standard for obedience and worship, followed his heart for forty days to prepare himself to save the world.

Then there was Saint Paul.

The revelation of Jesus Christ to Paul at Damascus is one of the most famous stories in the New Testament (Acts 9:1-9). But what took place in the months immediately after Paul saw Jesus is one of the great mysteries of the Church. This most fascinating chapter of the Apostle’s life remains unknown, lost to the world of the Spirit and within Paul’s own august heart, as deep as the abyss, as high as the sky.

This period, short as it was, is one of the most important in the history of the world, in the history of salvation, since it encompasses the event on which, humanly speaking, the conversion of the entire civilized world to Christianity depended, vis-à-vis the conversion of the Apostle. [1]

The story of Paul’s apostolate began in eternity. Paul received a divine calling from God to preach to “gentiles, kings, and Jews” (Acts 9:15b). He discerned his commission during a forty-day desert journey in imitation of Christ (see 1 Cor 11:1). At baptism, Paul’s eyes, blinded by the light of Christ, were opened and “things like scales fell from his eyes” (Acts 9:18). He stayed “some days” with the disciples in Damascus and then was led by the Spirit into the desert to pray and to discern as had Israel, Moses, Elijah, and the Lord. The biblical tradition of purification in the wilderness was a part of Israel’s heritage and a tradition with which Paul would have been very familiar. When the time came for him to make his next move, he did what Moses, Elijah, the Israelites, and Jesus did: he opened his mind and his heart to the Spirit and allowed himself to be led into the desert and to be tested, amid the howling winds, the scorching heat, the wild ass, the adder, the vulture. He had no idea where he would end up, or when he would return, or whether he would ever again see Jerusalem.

For Israel, the Spirit was the manifestation of the saving power of God. From the beginning, the Spirit created the world and had been with God’s people throughout the millennia. The Spirit spurred the judges to action and saved the Israelites from its enemies by forming a confederacy of the twelve tribes. The Logos provided what the kings needed to consolidate the tribes into a powerful nation. The prophet Samuel, horn in hand, anointed David in the midst of his brothers. “And from that day the Spirit rushed upon David” (1 Samuel 16:13). The Light of the Lord led Moses and the Israelites through the wilderness after they escaped Egypt and the Holy Spirit prompted Jesus to take up his calling to bring the good news to all people from the moment he returned from the desert.

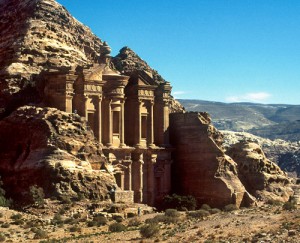

The Bible frequently mentions “Arabia,” but of his time there Paul wrote little—“I went into Arabia” (Galatians 1:17b). Arabia is identified as the enormous tract of desert southeast of Damascus, the realm of the Nabataeans, ancient Arabs who lived in the city of Petra, hewn from the rock so red like blood. Most of the central region of the Arabian peninsula is wasteland, with scattered oases, the most fertile parts of the area lying along the fringes and the coast of the Red Sea. [2] Arabia as a location is as much a spiritual destination as it is a place on the map. Paul let the Holy Spirit be his guide, to direct his steps toward the places to which God wanted him to see.

What took place during Paul’s visit there is as much of a mystery as where he went. Scholars and Church Fathers, most notably Jerome, believed that Paul most certainly attempted to evangelize the Nabataeans and any Jews living there. The purpose of his trip was manifold: to think about his calling, to pray with the Scriptures he carried around inside his head from so many years in diligent study, and to see the face of Jesus again, whose radiance captured Paul forever. The visions he experienced in Arabia were beyond his ability to put into words. In his Second Letter to the Corinthians, he mentions having been caught up into the “third heaven” (12:2), writing of his experience in the third person so as to deemphasize any claim to a personal religious experience outside his apostolic mandate. As a prophet he felt forbidden to express the unutterable visions of the individual so he adhered to the convention of sealed revelation like Daniel or John the Divine. These revelations and locutions he experienced in the wilderness and upon the mountain shaped Paul’s thoughts on his life, his minister, the world, and God. Even if he could not adequately describe them through speech or writing—trained as he was in Greek rhetoric—he could not forget them because the Lord had embossed his seal on the soul of the apostle and written his legend upon Paul’s heart.

Paul walked on through the wilderness to cleanse himself and ascend the summit of revelation and to see the face of the Lord once more, like Moses, who said, “Show me your glory!” (Exodus 33:7-23). These holy visions so pure and profound that the mystic could not express them even in prayer and so he continued to yield to and appeal to the Spirit (Romans 8:26).

Returning to Damascus, where he remained for “three years” (Galatians 1: 18) Paul affirmed the calling and promised to be faithful to God for the rest of his life. During this time he labored underground because the men who had betrayed him and forced him to flee after his baptism remained at large and now they had an added incentive to turn him in: Aretas had put a price on his head. Was it something Paul said when he preached to the king? When Paula arrived in Petra, Aretas was embroiled in a feud over land with Herod Antipas, who also angered Aretas by divorcing his daughter to marry Herodias (Mark 6:17-18). A cryptic entry in the second Corinthians letter matches with what Saint Luke wrote about Paul in Damascus in the Acts of the Apostles: “At Damascus the governor of Aretas guarded the city in order to seize me, but I was lowered in a basket through a window in the wall and escaped his hands” (cf Acts 9:25). Had Aretas dispatched soldiers to apprehend Paul in Damascus because he wanted him dead or because he felt a calling to the faith and wanted to finish listening to what Paul had had to say?

Instead of returning to Petra, Paul went to Jerusalem where he joined Peter and the other apostles and began his life’s work as a tireless evangelizer who helped build the Church and changed the world.

_____________________________

[1] The Heathen World and Saint Paul, or, Saint Paul in Damascus and Arabia. Rev. George Rawlinson, MA, 19th-century canon of Canterbury and Camden professor of Ancient History, Oxford.

[2] Illustrated Dictionary and Concordance of the Bible.