*Editors Note: Over the next few weeks William Bornhoft and myself will be in a dialogue over the role of traditionalists within the Church today.*

*Editors Note: Over the next few weeks William Bornhoft and myself will be in a dialogue over the role of traditionalists within the Church today.*

Mr. Bornhoft,

I read your article “The Latin Mass is Not the Key to the New Evangelization” with interest, and it must also be admitted, with a bit of bewilderment. With interest because a lot of people, even some mainstream voices, were talking about traditionalism and the Latin Mass, something I hold dear to my heart. Bewilderment because I believe that many of the complaints you use against traditionalists (or “TLM Millennials” as you call them) showcase an unfamiliarity with a lot of traditionalist thought, but also because I think these complaints , when examined closely, probably end up having a greater danger for your own article.

I think this statement is the one I’d like to begin our focus on:

Anyone interested in seeing the Catholic faith thrive in the world, rather than be ignored, should be concerned about a generation of Catholics who oppose reforms that the vast majority of Cardinals supported 50 years ago.

While I hardly speak for all traditionalists (don’t believe what the internet tells you, we are a pretty diverse group who take a wide variety of positions), I suppose I would object to such a statement with the following:

A Majority of Cardinals?

Why is it significant that “a majority of cardinals 50 years ago backed something”, ergo we should back it as well? At the end of the day, the title of Cardinal is an honorific. It doesn’t have inherently more authority than a bishop. Even then, there were several cardinals who were far more in agreement with traditionalists believing that many of the liturgical reforms following the Second Vatican Council were misguided. This was especially the case during the pontificate of St. John Paul II. Even if many preferred the Ordinary Form, they were increasingly critical of saying mass versus populum, began to advocate receiving communion on the tongue, took a very negative view towards altar girls, etc. Are we forbidden from taking this position because “a majority” of a certain timeframe believed otherwise?

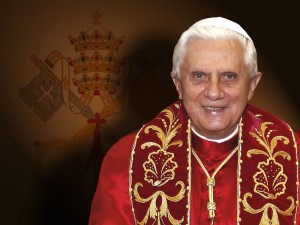

I suppose what I find most troubling about this view is that it cannot appeal to Church teaching. The nature of the Church necessitates that there will be differing schools of thought and opinion about matters that are not settled doctrine. This is because these points surround how to apply doctrine, and by its very nature, these points are sometimes more or less relevant depending on the time. As a result, they are also by their nature subjective. While you might dismiss the importance of a priest saying Mass ad orientem, then Cardinal Ratzinger viewed such a dismissal as one of the key problems behind the collapse of liturgical catechesis. There is no eternally “right” answer on these questions, so debates can and must take place. Your position seems to discourage them, and that is not the position of the Church. Benedict XV outlined the nature of these debates in Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum:

Again, let no private individual, whether in books or in the press, or in public speeches, take upon himself the position of an authoritative teacher in the Church. All know to whom the teaching authority of the Church has been given by God: he, then, possesses a perfect right to speak as he wishes and when he thinks it opportune. The duty of others is to hearken to him reverently when he speaks and to carry out what he says.

As regards matters in which without harm to faith or discipline-in the absence of any authoritative intervention of the Apostolic See- there is room for divergent opinions, it is clearly the right of everyone to express and defend his own opinion. But in such discussions no expressions should be used which might constitute serious breaches of charity; let each one freely defend his own opinion, but let it be done with due moderation, so that no one should consider himself entitled to affix on those who merely do not agree with his ideas the stigma of disloyalty to faith or to discipline.

I think this should be the framework from which we operate throughout this dialogue. You believe that in calling for many of these changes to be reversed, traditionalists are “at odds with the teaching of the Catholic Church” and that this action makes us “skeptical of Vatican II.” I believe we arrive here at the crux of the matter. Are we really opposing the Magesterium and the Second Vatican Council in these acts?

Can you show us where in the Second Vatican Council the topic of saying Mass versus populum is discussed? Where is communion in the hand or altar girls treated in Sacrosanctum Concillium? While they do speak of a vernacular liturgy, do they not also speak of the Latin language being retained and having a special place in the life of the Church?

When we examine this question, there is only one acceptable answer: Vatican II mandates none of the things talked about. To look at Sacrosanctum Concillium as a list of change/retain is to misunderstand the entire purpose of the document: it is a dogmatic constitution; therefore it is speaking on something of a timeless nature. It is speaking about the nature of liturgical reform first and foremost. While it does offer certain liturgical prescriptions (such as suppressing the hour of prime in the Divine Office), a future council could just as easily change that in applying the principles Sacosanctum Concillium talks about. If traditionalists can (and we can!) base our critique of the liturgical reform around why our position is consistent with the principles of the Constitution, then I would suggest your statements are found wanting.

The way to do this is not rocket science, and it is something that traditionalists have increasingly understood and embraced. The pontificate of Benedict XVI mostly settled the way to understand the Council, and it is in a way traditionalists can (and must) live with: that the Council must be presented within the greater framework of Catholic tradition. When looked at from the framework of the hermeneutic of continuity, we would argue that while these things being innovations does not disqualify them outright, one can be skeptical of the results the change would achieve, and continue to advocate that before changing these disciplines, we should seek to change ourselves as much as possible. This is entirely consistent with Vatican II, and hence I’m not really sure on which foundation you can continue to base your objections.

Regards,

Kevin