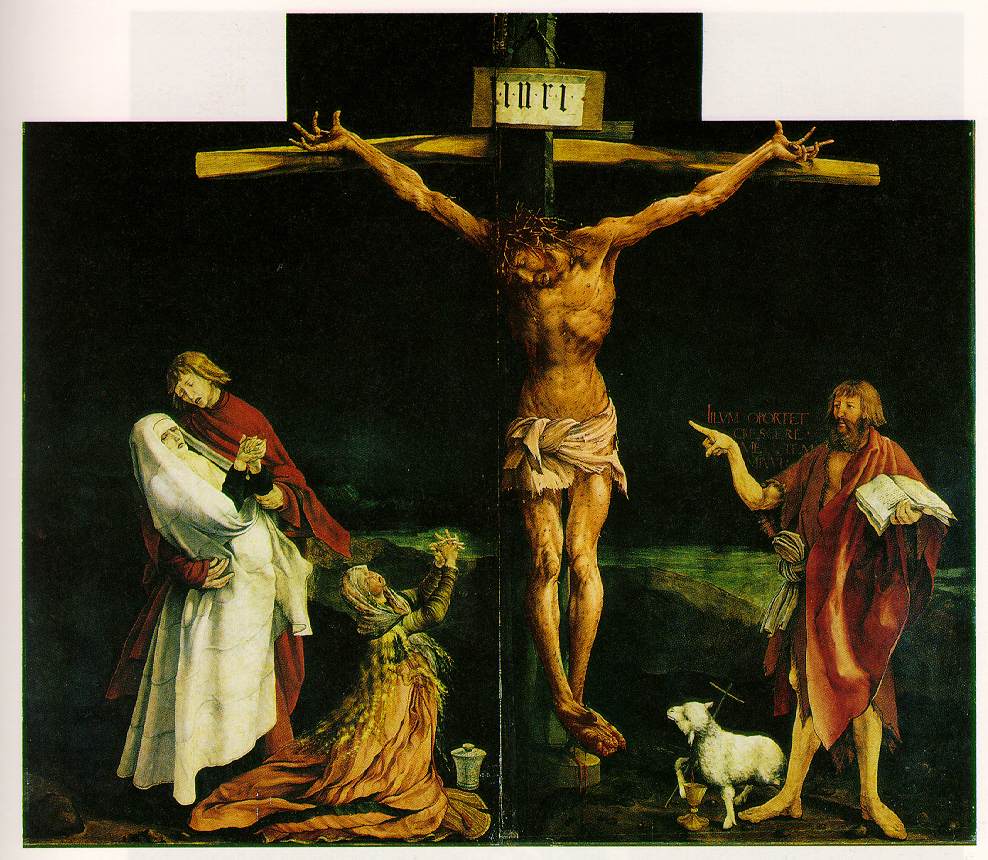

Over the centuries, Christian artists have produced innumerable portrayals of the Lord’s crucifixion, but none so terrible as Matthias Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, a work at once transfixing and repulsive.

The middle panel of the Isenheim triptych features Christ, pallid and emaciated and thorn-pierced, pinned to the tree. It is truly a garish scene, torn from some medieval nightmare: His limbs are gaunt and stretched; His veins taut, fat and dark like wet cord; His lips cracked and flecked with spittle; His nose swollen from fist and lash. There is no polish or sentiment, which is unusual for liturgical art.

Most intriguing are the Lord’s hands and feet, which Grunewald depicts as deformed, contorted. The feet in particular are elongated and misshapen: indeed, they are rather claw-like. Why does Grunewald depict the Lamb in such a frightening way? Why is there a hint of the demonic about the dying God-Man?

The mind flies immediately to the words of Saint Paul: “For He hath made Him to be sin for us, who knew no sin; that we might be made the righteousness of God in Him” (II Corinthians 5:21). On the cross, Jesus took upon His scourged and pummeled shoulders the sins of the world. He assumed all the evil and wickedness of mankind unto Himself, as the scapegoat assumed the wrongdoings of Israel. Yea, the Word gathered up the sins of humanity and destroyed them in the purifying fire of His divinity!

Is Christ’s beastly appearance an expression of this dimension of the atonement? In Grunewald’s imagination, the Lord’s unsightly and contorted body might just declare the Calvary event, by which mankind was ransomed from the darkness of the Devil and spared the just wrath of God.