For the past several weeks, Catholics around the Internet have been talking about a scandal, and, surprisingly, they’re more or less in agreement. It is a real-life scandal of a bishop who forgave a criminal for robbing from him. It is a fictional scandal of a criminal who broke parole, became a successful businessman and mayor, then spent the rest of his life as a fugitive, then illegally adopted the orphaned daughter of a prostitute. And it is the real life “scandal” that a movie based upon a musical based upon a novel that was once on the “Index of Forbidden Books” is now being discussed across the Internet as one of the greatest Catholic works of fiction of all time.

I have over 1400 Facebook “friends”–over 90% of them Catholics, mostly of the “conservative” sort, some more moderate or even liberal, and many are on various aspects of the spectrum-within-a-spectrum-within-a-spectrum that is known as traditionalism or radical traditionalism. Nearly everyone who has discussed the Les Miserables movie directed by Tom Hooper are agreeing with the sentiment in the first paragraph. A few think the musical is too “maudlin”, or just don’t care for sung-through musicals or musical dramas. Some have criticized some or all of the singing (I’m not a particular fan of Russell Crowe’s performance, but I don’t think he’s really bad, either, and I think Hugh Jackman does a great job, although he lacks the etherial quality of Colm Wilkinson’s legendary performances). Only one, person, however — a longtime Internet friend who is a member of the Society of St. Pius X — besides me raised the issue that the novel was on the Index, and my friend insisted that since Paul VI said the Index still retained its “moral force,” that means no Catholic should be involved with the novel, the musical, or any movie adaptation of either

Now, there is a common misconception about the Index. The Index was not, as many surmise, a list of “banned” books. The notion was not that under no circumstances should a Catholic read those books, but rather that they should only be read under guidance from a spiritual director or in an academic setting. Sometimes, throughout history, works that were on the Index at one point were later removed. (Les Miserables was apparently removed from the Index in 1959.) Works that were on the Index were often taught in colleges but banned for the average layperson merely for reasons of confusion. One critique of the Index, and one of the reasons for its elimination, was that so much secular literature had been published that the Church could not keep up with it all.

Pascal’s Pensees was on the Index (at least an edition annotated by Voltaire). St. Faustina’s Divine Mercy in My Soul was on the Index (although many “RadTrads” argue that it should still be banned, and that she should not have been canonized).

Just about every name in modern philosophy was on the Index, including Renes Descartes, whose devout Catholicism was attested by the fact that he converted the Queen of Sweden back to Catholicism from Protestantism. Maimonides, a necessary stepping-stone to Scholasticism, was on the Index.

Officially, the Index included books that were heretical or immoral, yet many authors who published during the Index’s tenure (Marx and Hitler, on the one hand, or Joyce and Lawrence on the other), were somehow able to escape its eye. Some have said that the Index focused on anti-clericalism, blasphemy or heresy. Recent scholarship into the Vatican’s much-discussed “Secret Archives” suggests that what was or was not included seems to be a matter of who the reviewer was. For example, the first reviewer to consider Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin worried it was a call to revolution, and almost banned it, but a second reviewer overturned the decision.

Today, if a Cardinal in charge of a Vatican Congregation issues an opinion, the general Catholic response pretty much boils down to whether one is inclined to agree with that opinion. Otherwise, people will say, “that’s just his opinion, and he’s not the pope.” This is especially true of decisions by lower level Pontifical Councils and other organizations within the Vatican. This is essentially what the Index amounted to: not the opinion, directly speaking, of the Holy Father, or even of one of the chief Cardinals of the Vatican, but the opinions of the reviewers who worked for the subdivision of the Inquisition/Holy Office/Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith that was in charge of the Index.

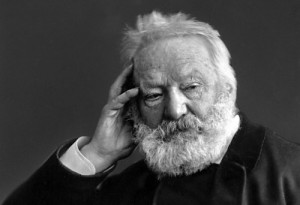

Now, why might Les Miserables have been included? There are several reasons. First, Victor Hugo was a Republican, in the 19th Century French sense of the word. He supported the French Revolution, had mixed feelings for Napoleon, and generally favored that liberty/fraternity/equality business. There’s an expression one often hears in old cartoons and westerns: “them’s fightin words”. In the 19th Century, “liberty, fraternity and equality” were literally “fighting words”, and the Church was distrustful of overturning political status quos. That’s why the Church initially opposed democratization, but it’s also one of the reasons why, in the late 19th Century, the Church began putting the brakes on Catholic monarchical movements that wanted to have counter-revolutions.

Prizing social order and peace, the Church was wary of political revolution, and notions of promoting non-law-abiding (criminal) behavior. Even though Catholic morality teaches that a law which does not conform to Natural Law is invalid, the Church was not comfortable at the time with telling people they could go around breaking the law—that’s still true today. This was a time of what Dietrich von Hildebrand called “ossification” in the Church. A few centuries before Victor Hugo, the great Mystic Doctors Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross were under the watchful eye of the Inquisition, to the extent that some of Teresa’s works were lost to history while being “reviewed.”

Prior to Vatican II, and even today in many circles, religious were warned against reading the Mystical Doctors. Carmelite nuns and friars have gone their entire lives without reading Teresa or John because their superiors told them, “That’s not for you. You’re not holy enough.”

A strange phenomenon of pre-Vatican II Catholicism was that the average layperson was taught a very narrow and “safe” version of the Church’s moral teaching. They were unlikely to comprehend what Catholic film critic Steven Greydanus pointed out in his appearance on The World Over Live: that the story of Jean Valjean perfectly exemplifies Catholic Social Teaching. St. Thomas Aquinas famously states that it is not theft for a starving person to take what is necessary for survival from someone else. Thus, when Valjean notoriously steals his loaf of bread in 1796 to feed his sister’s starving children, he does nothing wrong according to Catholic teaching (except maybe the parts about breaking the glass and holding the baker at gunpoint). Arguably, he does nothing wrong when he “steals” from the Bishop of Digne, either, since he is in desperate need, and the Bishop explicitly tells him, upon welcoming him in, “everything that is in this house is yours.” Valjean just took the Bishop at his word.

Nevertheless, to a Church deeply concerned about a replay of the Protestant Reformation, deeply concerned about revolutions fomenting around Europe, deeply concerned about preserving social order, these were dangerous sentiments.

Then there’s that bit about morality: Les Miserables depicts the fact that, yes, people do bad things, and sometimes moral decisions are very complex. The fact that the novel depicts prostitution has been a major reason for its banning by various secular authorities over the past 150 years. Once again, a very basic principle of Catholic moral teaching is that a person is only guilty of something if he or she chooses it freely. Victor Hugo shows again and again how people commit sins out of desperation, and he illustrates very vividly the Catholic teaching that when an individual commits a sin out of desperation, the guilt lies largely, if not wholly, with society, rather than merely with the individual. However, to the practical governing authorities of the Church, it is problematic to spread around these notions.

My daughters know the musical very well, since their mother and I are huge fans, and when I was talking about this topic at home, I said, “No one really knows why it was on the Index.” My eldest daughter, without missing a beat, suggested, “Fantine?” She was probably right. In countries and schools that have banned it, depiction of prostitution is the most cited reason.

One can see how the Church might be uncomfortable with some of these notions, but also how they are important illustrations of authentic Catholic moral and spiritual teaching. The real problem with the book, however, comes back to Victor Hugo’s politics. While he praises authentic spirituality and morality, Hugo was extremely critical of the Church as an institution. While some of his criticism was well deserved, this was exactly the kind of thing that the Index frowned upon (and why the Index needed to be abolished, given some of the problems we’ve started to clean up since Vatican II—indeed, it is quite ironic that traditionalists’ own critiques of the Church hierarchy would have landed their writings of the Index if it still existed).

There are sections of the novel where Hugo engages more in philosophizing than in narration, and this is where some of his problematic ideas come out. In one section, for example, he seeks to respond to complaints that convents and monasteries reflect a backward view of human society and should be abolished. While he ultimately comes out in favor of convents and monasteries, so long as their members are there by choice (noting how often people were confined to convents and monasteries for the wrong reasons), it is unclear sometimes whether Hugo is merely recounting, or agreeing with, the modernist attacks on Religious Life.

Ultimately, Les Miserables can be seen as an anticipation of Vatican II. It is almost a book-end to Francis Cardinal George’s famous speech to the Commonweal conference about liberal Catholicism having been an exhausted project. Hugo finds himself as both an admirer of authentic Catholicism and of the good ideas in modernity. He critiques the monarchy, but he often critiques the pre-Revolution monarchy precisely for being un-Christian. He condemns the Revolution for being godless. He praises the Restoration Monarchy for restoring what was good about the monarchy while maintaining the ideals of liberty and social reform promoted by the Revolution.