When I came back to the Roman Catholic Church, around 1975, Liberation Theology was very popular in my native Argentina. Even the elite Catholic high schools were using the Latin American Bible for their classes. This Bible, produced by Liberation Theologians, had pictures of Cuba as the “promised land” and guerrillas as the new evangelists. I covered my ears during most of the sermons to avoid listening to the politicized comments. At the time, Pope Francis was a respected 40-year-old Jesuit known as Jorge Mario Bergoglio. He never embraced the Marxist version, but he did accept some aspects of Liberation Theology.

Like Pope John Paul II, he recognized that the Christian message is about liberation. Rocco Buttiglione, John Paul’s philosopher friend, stated in an interview that Pope Francis and the late John Paul II share the belief that the Christian message comes to life “in the history of the people” and local cultures are essential to spread the good word. John Paul’s Polish culture played a major role in the way he expressed the Christian message. Can we argue then that the Argentine culture, so impregnated with Peronism, is playing a major role in Pope Francis’ message?

We can get some insights into the Pope’s thinking by reading Father Lucio Gera, who had a great influence on Francis as a theologian and teacher. Father Gera, who was born in Italy but spent most of his life in Argentina, argued that as a teacher the hierarchy needed to be careful with words and doctrine. Gera wrote that as pastors the hierarchy needed to embrace, and have a preferential option for, the poor. In his words, “there are today many profound ‘technical’ elements in economics which are not easy to perceive and those who do not understand need to be careful not to make a misstep, and use words where they do not belong.” Gera continued, “The bishops are not economic experts but they have to respond from the needs of a specific people: what the Church presents are the aspirations of the people. How to structure and make room for that is another issue.”

In several passages of Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis focused on the excluded. He states, “It is no longer simply about exploitation and oppression, but something new. Exclusion ultimately has to do with what it means to be a part of the society in which we live; those excluded are no longer society’s underside or its fringes or its disenfranchised – they are no longer even a part of it. The excluded are not the ‘exploited’ but the outcast, the ‘leftovers.’” Jean-Ives Naudet, the director of the Center for Economic Ethics and Research, and president of the Association of Catholic Economists, wrote that it falls to the economists, “to explain that the market economy is the one that includes and the Welfare State the one that excludes, especially given its bureaucratic character: ‘it is better to get your job from the market, than to receive an impersonal assistance that marginalizes.’”

The language of inclusion explains part of the popularity of Peronism. It recognized the existence of large segments of the population which were, or could be, convinced that they were being excluded from their society. Peron flirted with class struggle and blamed the exclusion on oligarchs and capitalism. He created a space for these large segments of the population. Some of us see it as a space bounded by the “slavery” of government dependency. Yet, those who felt empowered by this opening and the government handouts have remained faithful to Peronism for almost 70 years.

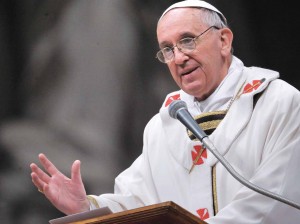

Pope Francis will not engage in class struggle, and will not endorse an “irresponsible populism.” The tone of his message seems directed to Christians around the globe who also feel that they have been excluded. Finally, they have their man at the top, someone who understands their plight. The mystical charisma of John Paul II, honed through decades of spiritual and pastoral life under the dark dominance of communism, and the intellectual and disciplined gifts of Benedict, the great German essayist and theologian, contributed to a new, extremely rich intellectual period in the Catholic Church. Pope Francis’ charisma comes from his identification with a culture in crisis, like the one he experienced in Argentina, with a weak rule of law, with pervasive corruption, crony capitalism and infatuated with populism. He knew and despised the hypocrisy of politicians, but despite his surrounding he was able to remain honest, clean, and principled. Pope Francis is hopeful, not only for the “people,” but for politicians and governments as well.

The Pope, who is prone to improvise in the use of language, is bringing a new style and strategy to the Vatican. Lucio Gera’s analysis might describe how Pope Francis will develop his agenda. Gera wrote, “We must take care not wanting to be extremely picky and plan and schedule everything. We need to leave room for improvisation, freedom. I think that Argentines sometimes prefer to leave too much to improvisation. They have perennial debates about soccer, not wanting to rely much on the coach and leave the initiative to the players.”

Over 95 percent of Evangelii Gaudium is devoted to spiritual liberation. The Roman Catholic Church will continue to be a much-admired teacher in this realm. However, on issues of economic liberation, the recent statements by the Pope, in addition to his determination to give more voice to the Vatican commissions and the episcopal conferences, will likely expand and democratize the debate about how to build a Christian and humane economy. As the Church is not an economic academy, the role of the laity will be crucial, and divergent opinions will not only be tolerated but welcomed by the Vatican.

Carlos Martinez, of Chile, founder and former editor of Communio magazine in Latin America, contributed to this piece.

[Editor’s note: This article first appeared at Forbes.com.]