Have you ever considered what might have happened if Jesus had come to earth not as God, but merely as a man, whose sole purpose was to heal suffering people from their infirmities? If so, you might be intrigued by Sympathy for Delicious. Its premise is simple: a young musician, who has lost his career and his hope after an accident leaves him paralyzed, discovers that he has the ability to heal others by laying his hands on them. However, he cannot heal himself.

Have you ever considered what might have happened if Jesus had come to earth not as God, but merely as a man, whose sole purpose was to heal suffering people from their infirmities? If so, you might be intrigued by Sympathy for Delicious. Its premise is simple: a young musician, who has lost his career and his hope after an accident leaves him paralyzed, discovers that he has the ability to heal others by laying his hands on them. However, he cannot heal himself.

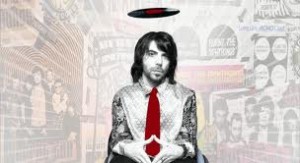

Writer Christopher Thornton and director Mark Ruffalo invite viewers to imagine what might happen to such a man and the people around him. Thornton portrays Dean O’Dwyer, an up-and-coming DJ on the underground music scene in Los Angeles, whose paralysis renders him unable to spin turntables, thereby ending his promising career. Homeless and depressed, sleeping in his car, Dean meets Father Joe Roselli (Ruffalo), a priest who works with down-and-outers on skid row.

When Dean inadvertently heals a homeless man and a blind woman, he immediately lays hands upon himself, to no avail. Word gets around, and Father Joe persuades the reluctant Dean to lay hands on the hundreds of supplicants who crowd skid row in hopes of a miraculous release from suffering. Upon discovering that Father Joe is getting some very generous donations for the work, of which he shares only the smallest amount, Dean angrily decides he will use the healing gift to gain him entrée into a promising band. They have a brief, successful stint as “Healapalooza,” (cut to montage of debauchery scenes). Money, women, drugs, adulation, heavy eyeliner… Dean has it all. First Father Joe has prostituted Dean’s gift, and now Dean is prostituting his own gift. Of course, nobody is happy. And when disaster occurs and Dean lands in jail, no one in the audience is surprised. We knew it was only a matter of time.

What happens afterward is more adventures in “what if.” What if Dean decides to take responsibility for all the bad choices he’s made? What if Joe, no longer Father Joe, just Joe, decides to apologize? What if Dean is offered a second chance to exercise his gift on someone he doesn’t like?

Here’s where the film gets interesting. Instead of writing a morality tale railing against the evils of hypocritical religious people, Thornton simply focuses on one man just like us, who hasn’t got what he wanted in life, but instead got something everyone else wants and is trying to take from him.

Sympathy for Delicious is no mere fanciful intellectual exercise. Thornton was paralyzed from the waist down in a rock climbing accident at age 25. Ruffalo’s brother Scott was shot and killed in 2008. Indeed, the film is dedicated to his memory. Says Ruffalo, “A lot of that struggle had to do with ‘Why?’ Where does this come from and how do I place it in the mythology of my life? How do I make sense of this?” Sympathy for Delicious was obviously the result of much pain and many sleepless nights. Does Thornton’s answer square with biblical teaching on the subject of suffering?

Clearly the doctrine of resurrection assures all believers that they will eventually live eternally in perfect bodies. There are those who believe that all bodily infirmities are the direct result of sin, and that repentance and prayer will result in perfect physical restoration in the present. This position leads to much grief and abuse, not a little disappointment, and even entire loss of faith when requests for healing are denied. In Dean’s case, this denial is made worse by the fact that those around him are being healed. It’s like your parents taking your brother to Disneyland and leaving you at home to do the chores.

And yet, biblical accounts suggest that sometimes God allows or even causes a physical malady in order to deliver a person from a spiritual malady. Our Heavenly Father wants the ideal for His children (perfect wholeness in all respects) and yet is dealing with fallen individuals in a fallen world. Sure, God could wave His hand over every sickness, broken bone and tumor, and make everyone 100% well. Yet we don’t see that often, even in cases where the victim is an innocent child, or a person who has great faith. Why not?

God does want the ideal for everyone. However, His offer of salvation is not immediately completed in those who accept it. Look around you. Presently, no one has a new body and a completely renewed mind. Hence the New Testament promises of future “perfection” to believers, and countless exhortations to obedience and growth.

Healing is tied to obedience, which is tied to belief in Christ. They are all of a piece. And it takes time. The Bible portrays God as a Heavenly Father whose priority is our spiritual/mental/emotional wholeness. Physical wholeness is something on which we tend to place top priority, but not so with God. “The things which are seen are temporal,” explains the Apostle Paul in 2 Cor 2:18, “but the things which are not seen are eternal.”

“Anything is possible with God. But He may not give you what you want,” explains Father Bill (James Karen) to Dean. There is no Jesus in this film. The Catholic faith is represented by the well-meaning but compromised Father Joe, who only finds redemption after taking a leave of absence from the priesthood. The [evangelical]Christian faith is represented by the buoyant and vaguely creepy Rene Faubacher (Noah Emmerich), a wheelchair-bound believer who takes Dean to healing services and exhorts him to believe. His clean-shaven, smiling face and penchant for brightly colored sweaters marks him immediately as an evangelical Christian, even before he utters a word.

Sympathy For Delicious has a small cast of principles, including such noteworthies as Juliette Lewis portraying the band’s emotionally unstable, pill-popping bassist, Orlando Bloom as its lead vocalist, and Laura Linney as its saccharine/sleazy manager. Ruffalo’s pacing is steady. His camera lingers often on Thornton’s scruffy/pretty face. While the majority of the film dwells in dark and wretched spaces, there are a few moments of grace to counterbalance this ugliness.

Viewers with sensitive ears should be warned that the film contains more f-words than you can shake a drum stick at. There is also some frontal nudity. The creators have spared no trouble to create a convincingly sleazy atmosphere, whether in the depths of skid row or the heights of stardom. Clearly, film’s target audience is not people of faith, but suffering people seeking answers for the age-old questions of pain and injustice. Thornton’s answer echoes the Rolling Stones:

You can’t always get what you want

But if you try sometimes you might find

You get what you need