In one of his typically simple, direct, and forceful homilies, Pope Francis warned recently against idols and idolatry. “We have to empty ourselves of the many small or great idols that we have and in which we take refuge, on which we often seek to base our security,” he told a congregation in Rome.

In one of his typically simple, direct, and forceful homilies, Pope Francis warned recently against idols and idolatry. “We have to empty ourselves of the many small or great idols that we have and in which we take refuge, on which we often seek to base our security,” he told a congregation in Rome.

The chances of people today bowing to Baal or burning incense to Diana of the Ephesians are probably not great. It’s a minor worry compared to everything else there is to worry about. But the Pope’s words become highly relevant when you realize he meant “idols” in a broader sense.

Just how broad became clear when, greeting new ambassadors to the Holy See in mid-May, Francis saw a form of idolatry at the root of the global financial crisis. In place of the “primacy of human beings,” he said, “we have created new idols. The worship of the golden calf of old has found a new and heartless image in the cult of money and the dictatorship of an economy which is faceless and lacking any truly humane goal.”

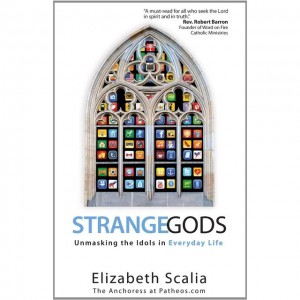

Pope Francis isn’t the only one to make the case against idolatry lately. His remarks coincide with the appearance of a book called Strange Gods (Ave Maria Press) that takes a close-up look at some varieties of idol worship in everyday life.

It’s the work of Elizabeth Scalia, well known to the blogosphere as The Anchoress. She also manages the Catholic channel of the popular Patheos website. Faithful readers know her as a thoughtful writer with a gift for down to earth eloquence. Her book is fresh evidence of both.

Scalia describes idolatry like this: “To place anything–be it another deity or something more commonplace like romantic love, anger, ambition, or fear–before the Almighty is to give it preeminence in its regard. To become too attached to a thought or feeling or thing is to place it between God and ourselves.”

The problem with doing this is–or should be–obvious. “When we attach ourselves to something other than God, God’s presence is blocked, unseen, and disconnected from our awareness.” Something else has taken the place of God, and that something is an idol.

But, you say, in no way am I tempted to do that.

Don’t be too sure. Idols can and do take many forms, wear many different disguises suited to our individual tastes and weaknesses. For one person, idolatry is all wrapped up in the satisfaction that comes with doing terribly hard work. For someone else, it’s the different set of gratifications involved in relaxing and taking it easy (including taking it easy on the job).

Scalia suggests the scope of this diversity in organizing her bestiary in chapters bearing titles like “The Idol of I,” “The Idol of Coolness and Sex,” and so on. There’s even a chapter on “super idols”–those personalized composites of one’s very own favorite ideologies that, taken together, “give us permission to hate and tell us our hate is not just reasonable but pure.”

As one might expect, the temptation to idolatry is both seductive and deceptive. Other people’s idols are usually obvious, but our own tend to be invisible–to us, that is. Seeing them clearly so as to resist them and root them out requires help–the help that comes from rigorous, regular self-examination, reception of the sacrament of penance, and spiritual counsel from a reliable guide. For beginners and those farther along, one such guide is Elizabeth Scalia’s Strange Gods.