A writer who practices his art at home does not want to turn his place of residence into a library warehouse. And so, every so often, in order to maintain a dynamic equilibrium between acquisitions and dispersals, he must sift through his material and separate the transitory from the enduring. It is a practice akin to gardening in which one separates the weeds from the perennials. Some material remains stubbornly attached to time, while other material becomes the stuff of history. Or so one believes. It is not an exact science.

A writer who practices his art at home does not want to turn his place of residence into a library warehouse. And so, every so often, in order to maintain a dynamic equilibrium between acquisitions and dispersals, he must sift through his material and separate the transitory from the enduring. It is a practice akin to gardening in which one separates the weeds from the perennials. Some material remains stubbornly attached to time, while other material becomes the stuff of history. Or so one believes. It is not an exact science.

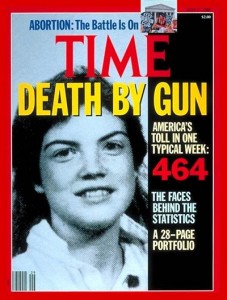

I was engaged in such sifting recently and enjoyed the serendipitous feeling of discovering literary items that seemed to improve with time. One item, however, arrested my attention in a jarring manner. It was the cover feature for the July 17, 1989 issue of Time: “Death By Gun: America’s Toll in One Typical Week.” Why would I hold onto this issue for more than two decades? I surmise that it was to remind me of the many mature souls who die violently before their time, their lives coming to an end in great numbers, like falling leaves. The words “before their time,” convey a piercing sadness: what could be, will not be. There can be no turning back.

Time dedicated a 28-page portfolio in this issue to memorialize the deaths of 464 Americans who were killed by gunfire over the course of a single week. In order to further humanize this harrowing statistic, it provided the faces of most of these casualties. Re-visiting this issue is like walking through a cemetery, but even more poignant because one knows that all these deaths were unnecessary. Each face evoked a shudder. The old Roman, Terence, was right: “I am man, I consider nothing human alien to me” (Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto). It is the nature of any genuine pro-life sensibility to moved by the death of anyone.

Time dedicated a 28-page portfolio in this issue to memorialize the deaths of 464 Americans who were killed by gunfire over the course of a single week. In order to further humanize this harrowing statistic, it provided the faces of most of these casualties. Re-visiting this issue is like walking through a cemetery, but even more poignant because one knows that all these deaths were unnecessary. Each face evoked a shudder. The old Roman, Terence, was right: “I am man, I consider nothing human alien to me” (Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto). It is the nature of any genuine pro-life sensibility to moved by the death of anyone.

The more I studied the specific causes of these deaths, however, the more I realized that these tragedies were not so much the result of guns, but from a loss of the will to live and the inability of people to get along with each other. A large proportion of the deaths were by suicide. How many suicides took place that week, I wondered, in which the gun was not the instrument of death? The real enemy of life lurked deeper than the gun.

On page 18 I saw a face that I recognized. It belonged to Thomas Stallcup who, at age 67, turned a shotgun on himself. In his heyday he played shortstop for the Cincinnati Reds under the name Virgil Stallcup (what a great name!). I was once the proud owner of his baseball card. He was No. 108 in the 1951 Playball series. His portrait displayed the epitome of joy and confidence. The fact that his career stats were indeed modest (his lifetime batting average is .241) did not matter. To young baseball card collectors, he was an icon, a success story, a hero larger than life. And now, Time informs me, this erstwhile role model is now a grim statistic who has been absorbed by an even grimmer statistic — 464. The fact that the photo that Time selected was the same one that appeared on his card, made the pictorial announcement of his death morbidly ironic. Icons are not supposed to fall!

Hollywood stars are also regarded as larger than life, though the disparity between their image and their behavior is the embarrassing grist for tabloid journalism. We believed in Virgil Stallcup, we youthful, naïve baseball card collectors. It is shocking to learn that there came a time in his life when he may not have believed in himself.

Life, as the poet John Keats describes it, is “A fragile dew-drop on its perilous way from a tree’s summit” (Sleep and Poetry). The great paradox is that our greatest value, life, travels with fragility as its constant companion. Hence, the profound poignancy of human existence. “We are all in the same boat in a stormy sea,” wrote G. K. Chesterton, “and we owe each other a terrible loyalty.”

Why, we may ask, does society view those who try to prevent suicide as humanitarians, and those who try to prevent abortion as fanatics? Both these cohorts are defending life. No “seamless garment” here. It is fair to conclude that our society is ambivalent about life. The fragility can be fearful, and the storms can be startling. And that’s the core of the problem. Life demands courage, support, faith and hope. It does not arrive without its challenges. And who amongst us can meet these challenges alone?

We have detached “choice” from community and are now paying a heavy price on a community level. We have been duped by the myth of autonomy. Yet, not even Major League baseball players are autonomous, though they may appear to be when looking invincible on their bubblegum cards. None of us is larger than life. Nonetheless, each of us is larger than being a mere individual. We are communal beings called to love each other. That’s not how we get ourselves on baseball cards, but that may be the best way to avoid being part of the kind of grim statistic that Time assembled more than two decades ago.

This article courtesy of Human Life International.