The Guttmacher Institute released a brief report titled Unintended Pregnancy and Abortion in Uganda in which they make their case for why increased contraception and access to “safe” abortion will reduce maternal mortality. Briefly, their argument is that unintended pregnancy in Uganda is high, and this is because women don’t have access to contraceptives. Because of these unintended pregnancies, women seek abortions, which Guttmacher claims are often “unsafe” due to a combination of confusing laws, lack of knowledge regarding one’s options, and stigma due to a pervasive negative attitude toward abortion.

The Guttmacher Institute released a brief report titled Unintended Pregnancy and Abortion in Uganda in which they make their case for why increased contraception and access to “safe” abortion will reduce maternal mortality. Briefly, their argument is that unintended pregnancy in Uganda is high, and this is because women don’t have access to contraceptives. Because of these unintended pregnancies, women seek abortions, which Guttmacher claims are often “unsafe” due to a combination of confusing laws, lack of knowledge regarding one’s options, and stigma due to a pervasive negative attitude toward abortion.

The Guttmacher Institute, founded as a research division of Planned Parenthood, predictably offer their boilerplate recommendations: more contraceptives to reduce the “need” for abortions, and more access to “safe” and “legal” abortions for when contraceptives fail or a pregnancy turns from “wanted” to “unwanted”, if the unborn child is diagnosed as ill, disabled, or, in some cases, female.

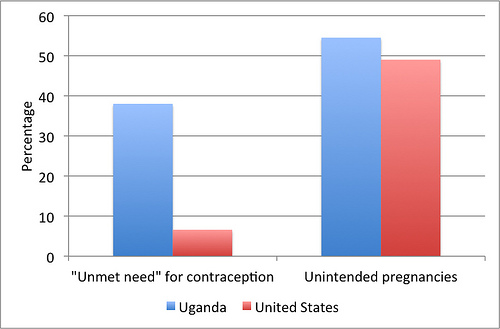

Guttmacher estimates that just over 54% of pregnancies in Uganda are unintended, and state that “The high level of unintended pregnancy and the gap between actual and desired fertility in Uganda can be attributed largely to insufficient contraceptive use.” According to the latest numbers from the United Nations Statistics Division, “unmet need” for contraception in Uganda was 38% in 2006.

Just for the sake of comparison, let’s look at the numbers from the United States: Guttmacher claims that 49% of pregnancies in the US are unintended, yet the UN Statistics Division puts “unmet need” for contraceptives in the US at only 6.6%, as of 2008.

As illustrated by this graph, the Guttmacher Institute’s assumption that more contraception will reduce unintended pregnancy rates in Uganda could stand a bit more scrutiny:

Relationship between “unmet need” for contraceptives and unplanned pregnancies in Uganda and the United States

Multiple conclusions can be drawn from this: first, the concept of “unmet need” is highly flawed (which experts have demonstrated), yet it is continually being used by organizations like UNFPA to demand funding – most recently 8.1 billion dollars a year to saturate the world with contraceptives.

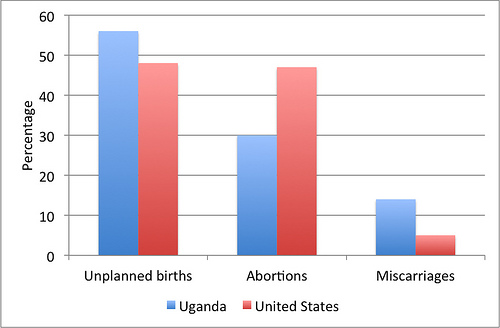

Second, access to modern contraceptive methods isn’t enough to stop unintended pregnancy, as the United States numbers clearly indicate. So what happens to those babies conceived unintentionally?

Outcomes of Unintended Pregnancies (United States vs. Uganda)

It should be noted that the Guttmacher report pays no attention whatsoever to the alarmingly high rate of miscarriage, which is almost three times higher than that of the comparable group in the United States. Instead, the report “highlights steps that can be taken to reduce levels of unintended pregnancy and unsafe abortion, and, in turn, the high level of maternal mortality.”

Since the Guttmacher Institute’s strategy on unintended pregnancy seems unlikely to work, their strategy for reducing maternal mortality would seem to hinge on dealing with unsafe abortion. The exact percentage of maternal mortality in Uganda attributable to abortion is hard to pin down: Guttmacher cites an unpublished report from the 1990s claiming a rate of 21% and a statement by the Minister of Health in 2008 claiming 26%. However, when Uganda’s Ministry of Health issued its annual report for 2011-2012, they attributed 13% of maternal deaths to abortion, which is consistent with global estimates, and, in fact, lower than the 18% rate the World Health Organization (WHO) cites for the East African region, which includes Uganda.

In addition to the Guttmacher Institute, the Center for Reproductive Rights also relies on the highest available estimate of maternal mortality due to abortion. Once again, their goal is explicit: “increasing access to safe abortion services.”

It seems that Uganda does not share their priorities. Uganda’s health ministry has been clear in defining the interventions that will improve maternal mortality. From their Strategic Plan for 2010/11-2014-15 (PDF):

“The main factors responsible for maternal deaths relate to the three delays – delay to seek care, delay to reach facilities and intra-institutional delay to provide timely and appropriate care. Slow progress in addressing maternal health problems in Uganda is due to lack of HR, medicines and supplies and appropriate buildings and equipment including transport and communication equipment for referral.”

In other words, general improvements in medical infrastructure and transportation, the same things that have reduced maternal mortality or kept it low in many countries with laws restricting or prohibiting abortion, such as Ireland, Malta, and Sri Lanka. WHO researchers point out that in Latin America, good healthcare infrastructure “has kept the mortality relatively low in Latin America, and the unsafe abortion case fatality rate is just about equal to that in Europe,” despite the lack of liberal abortion laws in the region.

If the Guttmacher Institute or the Center for Reproductive Rights were truly serious about saving women’s lives in Uganda, they would not rely on relatively unsubstantiated (and certainly debatable) numbers on abortion-related maternal mortality simply because they are the highest available estimates. To do so would be to risk underestimating the rates at which other complications occur, like hemorrhage or infection or underlying health problems caused by poor nutrition, such as anemia. Furthermore, promoting access to abortion would do nothing to improve the overall status of health care in Uganda, to say nothing of ensuring access to good roads and bridges that are crucial in ensuring prompt medical attention for everyone, including expectant mothers.

Ultimately, the focus on Uganda from these pro-abortion groups comes down to one very important fact. As the Guttmacher report helpfully points out in its opening sentence:

“Uganda, a country of nearly 35 million (including 8 million women of reproductive age), has one of the highest rates of population growth in the world.”

And, what’s more, the Ugandan people don’t seem to share Guttmacher’s view that this is a bad thing:

“Although desired fertility is declining, many Ugandans still want large families and do not approve of abortion.”

The Guttmacher Institute is using questionable data to push a flawed agenda on a country that does not require its help to establish sound health priorities.