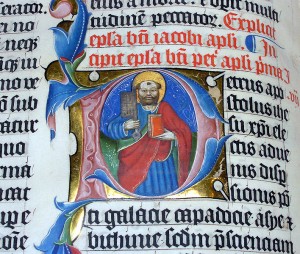

The First Epistle of Peter is the second of the seven “catholic” or universal epistles written and circulated to the faithful throughout the world during the first century following the birth of Jesus Christ. The Apostle Simon Peter wrote this short letter, in just 105 verses. Or the letter might have been dictated to Silvanus, a faithful scribe who also was a companion of Paul. That First Peter is authentic teaching from the prince of the apostles is hardly disputed. First Peter is ALL Peter, and it is grounded in the saint’s own recollection of the days he spent with the Savior before the Ascension. I do not think that it would be a stretch to say that those were the happiest days of Peter’s life. Which is not to say that Peter was unhappy after Christ’s death, but only that those days that followed the Resurrection were decidedly different. How could they not have been? The days before Peter spent wondering how such a reality as the Word Made Flesh could be true. The days between the Resurrection and the Ascension he prayed with the community and wondered whether things would ever be the same, how they could survive without Jesus as they then understood him. And there ever after Peter lived in the excitement and joy of proclaiming the Word until he met Christ anew in the kingdom of heaven to which he had been entrusted with the keys.

The First Epistle of Peter is the second of the seven “catholic” or universal epistles written and circulated to the faithful throughout the world during the first century following the birth of Jesus Christ. The Apostle Simon Peter wrote this short letter, in just 105 verses. Or the letter might have been dictated to Silvanus, a faithful scribe who also was a companion of Paul. That First Peter is authentic teaching from the prince of the apostles is hardly disputed. First Peter is ALL Peter, and it is grounded in the saint’s own recollection of the days he spent with the Savior before the Ascension. I do not think that it would be a stretch to say that those were the happiest days of Peter’s life. Which is not to say that Peter was unhappy after Christ’s death, but only that those days that followed the Resurrection were decidedly different. How could they not have been? The days before Peter spent wondering how such a reality as the Word Made Flesh could be true. The days between the Resurrection and the Ascension he prayed with the community and wondered whether things would ever be the same, how they could survive without Jesus as they then understood him. And there ever after Peter lived in the excitement and joy of proclaiming the Word until he met Christ anew in the kingdom of heaven to which he had been entrusted with the keys.

Peter is one of the most compelling, challenging, and best-loved characters in the New Testament. To Peter no small amount of ink and paper has been devoted. He even put a little of his own ink onto paper in the form of two letters that bear his signature. Peter is featured prominently in all four gospels (with varying characterizations from each evangelist) and nearly half of the narrative of the Acts of the Apostles. Saint Paul mentions Peter in his First Epistle to the Corinthians (15:5) and also in his Epistle to the Galatians (2:11-14), additional canonical writings that give further insight into his persona. In Peter’s two extant letters, First and Second Peter, he writes to Christians living amid temptation and persecution, days very much like our own. As with the other catholic epistles (James, 2 Peter, 1, 2,3 John, and Jude), First Peter exists to explain Christian doctrine and to support early believers by encouraging them to keep the faith. These universal letters are vital to understanding the story of God as expressed in saving Scripture and must be read, prayed with, reread, annotated, memorized, cherished, and loved. First Peter is a first-person viewpoint on the entirety of salvation written by the one man in human history who knew Jesus better than anybody: the apostle Simon Peter, the fisherman from Galilee.

That First Peter was placed toward the end of the New Testament attests to its importance in the fulfillment of the prophecy of a New and Eternal Jerusalem. The work gives us pause for consideration before we reach the end of the story of God, Revelation, which is really the beginning. “In the beginning” (Genesis 1:1) marks the end of darkness. “Come Lord Jesus” (Revelation 22:20) calls upon the world’s only Light. The Christian is a missionary in a decidedly anti-Christian world. The “chosen sojourners” to whom Peter writes are the followers, who, seeking to live as God’s people, feel alienated from their previous religiosity (they are mostly pagans and Jews) and from society. This revelation is not a spot occurrence. It does not happen once and then stop. Revelation, either personal or communal, is the acknowledgement that God is real, that he is actively and personally involved in human events, and this knowledge is worth accepting and pursuing because what we do can encourage greater spiritual growth and devotion to God, the source of revelation, and Jesus, the fulfillment of Divine Revelation.

Go into the world and preach the gospel to every creature. Whoever believes and is baptized will be saved; whoever does not believe will be condemned. These signs will accompany those who believe: in my name they will drive out demons, they will speak new languages. They will pick up serpents, and if they drink anything deadly it will not harm them. They will lay hands on the sick and they will recover. (Mark 16:15-18)

Peter had one ambition: to be a disciple. Unlike James or John, the sons of Zebedee, “The Sons of Thunder” or Boanerges, Peter did not actively pursue a leadership role among the college of apostles, and yet he became known as the “spokesman.” By his own assessment he was that “sinful man” who felt unworthy to be a disciple after witnessing the cure of his mother in-law (Luke 4:38-39) and hauling in the miraculous catch of fish (Luke 5:1-11). Seeing was believing because it affirmed his burgeoning faith—but it wasn’t enough. Peter had to hang in with Jesus until the very end, at least, until he denied him, which is part of what makes the story of Jesus and Peter such a heartbreaking contradiction, that the Rock of faith should crumble when Jesus needed him most. And how was Peter rewarded for caving in?—Jesus made him “pope.”*

Christ was a mystery that Peter wanted to spend the rest of his life trying to unravel while knowing full well that it was impossible. For three years Peter followed Jesus during his ministry; he listened to the Lord preach, tell his parables, and witnessed his healings, raising the dead, and driving out demons. These happenings led to Peter’s confession of faith at Caesarea-Philippi, when knowledge that Jesus was the Messiah came to Peter through divine revelation. “You are the Christ, the Son of the Living God.” … “Blessed are you, Simon, son of John, for flesh and blood has not revealed this to you but my heavenly Father” (Matthew 16:13-20). Peter could not have figured this out on his own but he certainly had a hunch that Jesus was who he claimed to be and this also Peter confirmed: “Now we know, and are convinced, that you are the Holy One who has come from God” (John 6:69).

There are multiple dimensions to understanding this greatest of saints. There is the Peter of history and biography, the fisherman born at Bethsaida who became the leader of a band of followers that grew into a worldwide organization known as the Roman Catholic Church. There is the theological Peter, that “rock”. Ultimately the Peter we want to know and to learn from and to love is the Peter of Faith, that one who received from Jesus the keys to the kingdom and continues to lead others to the redemption he himself graciously received.

And the Lord turned and looked at Peter. And Peter remembered the words of the Lord, how he had said, ‘Before the cock crows today you will deny three times that you know me.’ And he went out and wept bitterly. (Luke 22:61)

It would seem that Peter’s denial of Jesus disturbed Peter more than it hurt Jesus, who already had forgiven Peter even as he uttered his prophecy. The denial followed by the look and the mercy of God urged the apostle to lead the Church as recorded by Peter’s contemporary Luke in Acts of the Apostles. Peter knew that he owed a debt to the Lord and it motivated him to take action, much the same way that the vision of Jesus that Paul received at Damascus impelled Paul to recount it for the rest of his life. Both men suffered blessed martyrdom—both deaths prophesied by Jesus—cementing their legacies as twin pillars of the Church. This is not to say that Peter was motivated by guilt any more than Paul was running scared. Love is a greater motivator than self-reproach or fear because love is of God that has been wrought in eternity (1 John 4:16b). Peter knew that he had been rescued from his fears and this kept him moving all the days of his life. In Acts he steps into his breakout role, from follower to leader, a miracle worker like Jesus, who cures the sick, raises the dead, and casts out demons, a holy man whose grace others received as his shadow passed across them. Peter was as much a zealot of Christ as was Paul and every bit as much of a fool. And it was all for love, all for the sake of the name. And what a name! the very Word of God that created us all. “There is no other name under heaven nor on earth by which we may be saved” (Acts 4:12).

Reliable tradition reports that Peter arrived at Rome on his third and final mission circa AD 64. On Vatican Hill near the Necropolis he was crucified upside down at his insistence because he felt himself unworthy to die as did his merciful Lord. Instead of looking down on earth he looked straight into heaven and he it was who held the keys. This happened to fulfill the prophecy spoken by Jesus to Peter prior to the Ascension.

Amen, amen, I say to you, when you were younger you used to dress yourself and go where you wanted; but when you grow old, you will stretch out your hands and someone will lead you where you do not want to go. He said this signifying by what kind of death he would glorify God. And when he had said this, he said to him, “Follow me.” (John 21:18-19

Follow me. These are the words that reminded Peter of the call he first received that day on the shore of the Sea of Galilee when his brother Andrew ran up to him and said, “We have found the Messiah.” Was it possible for them not to tell somebody else?

*Peter as “pope” would not have been quite how we understand the papacy today, for like so much of the Church the Holy See has developed over the course of the centuries. Regardless, Peter’s primacy has always been upheld and maintained.