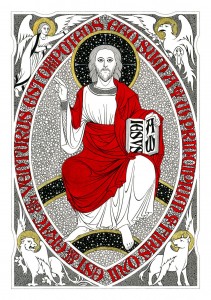

Intricate details and deep meaning characterize Daniel Mitsui’s religious art, which he renders by hand using ink on paper or vellum. Mitsui draws biblical subjects and saints according to the conventions of traditional iconography. More than being just representations of scenes and persons, Mitsui’s works are visual theological treatises. For example, his Pentecost shows not only tongues of fire on the heads of Mary and the apostles; it also shows seven doves representing the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, Old Testament prefigures, and the four Latin Fathers. More about Mitsui’s artistic philosophy can be read about here.

Mitsui embellishes his religious art with biological motifs, biological illustration being another specialty of his. There is a reason for this juxtaposition of biological and religious art, as Mitsui explains in this interview where he talks about his work.

—–

How did you get started in art?

I have been drawing for as long as I can remember.

What made you decide to focus on religious art and biological art in particular? Is there a special reason why you include biological motifs in your religious art?

From early childhood, I remember an attraction to anything resembling medieval art: Lego castles, Eyvind Earle’s painted backgrounds to the Sleeping Beauty animated motion picture and Trina Schart Hyman’s illustrations to St. George and the Dragon were particular favorites. At about the age of 14, I encountered reproductions of illuminated manuscripts for the first time, and was immediately fascinated. I imitated these in my own drawings, but the subjects were not yet religious. Although I had faith and thought of myself as a Catholic throughout my childhood, I was not baptized, and did not regularly attend Mass or receive formal catechesis.

I dabbled in other artistic idioms during late adolescence and in college: I drew, painted and made prints based on the Surrealist art of Max Ernst, and for several years I considered a career as a comic strip artist or film animator. At the age of 22, having been received formally into the Catholic Church and embracing its practice, I was ready to return to medieval art as well. This is when I began to concentrate on religious subjects.

My artistic specialty has always been detail; I like looking at intricately detailed things, and drawing them. This is what attracted me to biological illustration. I don’t draw many purely biological pictures anymore; not because I have lost interest, but because I do not receive many commissions for them.

Some of the biological imagery in my religious art is purely ornamental. However, I am more and more trying to adopt the theophanic worldview of medieval Christianity, in which everything is an image of God. Medieval authors produced books called bestiaries, herbals and lapidaries, in which the religious symbolism of the animal, vegetable and mineral kingdoms are explained. By studying these books, and by adopting a common worldview to their authors, I hope to make the natural decorations in my artwork more specifically meaningful.

What or who are your influences?

The short answer to that question is: medieval art. There is scarcely any work of art produced within Christendom during the Middle Ages that I do not like. Medieval art is traditional, linguistic, symbolic and mathematical; visually, it is defined by precision, ornament and horror vacui. There are many other kinds of art that I like as well, but they always share some of these characteristics.

I am most strongly influenced by Northern European art from the 14th and 15th centuries. This, I think, is due to my choice medium: drawing. Were I a metalsmith, or an ivory or hardstone carver, I would probably be focued on 11th and 12th century monastic workshops; were I an architect, a sculptor or a stained glazier, I would probably be most interested in 13th century cathedrals. But two-dimensional art, in the form of illuminated manuscripts, incunabula, tapestries and oil paintings, really flourished in the late Middle Ages.

Manuscript illumination is my favorite artistic medium. I have not yet completed an entire illuminated book, but this is my ambition; all of the single leaf drawings that I have made to date are preparation for this. I could name hundreds of manuscripts that have influenced me; particular favorites include the works of Jean Pucelle, theBooks of Hours produced under the patronage of the Valois Courts, and the Sherborne Missal.

Early printed books are another strong influence, especially for my black and white drawings. I am working to start a publishing imprint (Millefleur Press) to produce my own versions of 15th century devotional blockbooks, such as the Ars Moriendi and the Biblia Pauperum. I greatly admire the work of early Parisian printers, including Thielman Kerver and the partnership of Philippe Pigouchet and Simon Vostre.

Millefleur tapestries have strongly influenced the decorative and landscape elements in my paintings lately. For the main subjects of my drawings, I tend to refer to 15th century panel paintings. Obviously I love the greatest masters of that era: Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden. But I am just as likely to find inspiration is the works of lesser known painters such as Nikolaus Obilman or Johann Koerbecke.

I also like to work in the style of the Northumbro-Irish manuscripts of the 6-9th centuries, especially theLindisfarne Gospels with its lacertine animals, intricate knotwork and rune-like calligraphy.

The artists of the Gothic Revival and the Arts & Crafts Movement lived long after the Middle Ages but shared many of the same artistic principles. William Morris in particular has influenced on my own art.

Outside of medieval and medievalist art, I am fascinated by Japanese woodblock prints. To date, I have made three drawings that transpose traditional subjects from medieval religious art into their style. I hope to do more of these soon, and also to attempt something similar with Persian, Mughal or Rajastahni miniatures.

Recently, I have spent a lot of time studying the Golden Age illustrators, but their influence has not shown up in my own drawings yet.

What artwork are you proudest of?

The Chi-Rho Monogram that I drew in 2010 especially pleased me, because I had been trying to draw something like it, in the style of the Lindisfarne Gospels, for about 15 years.

I take satisfaction in two things more than any specific work of art. The first is that I am able to support a family as a professional artist. Art has been my sole livelihood for the past three years. I take commissions, sell original drawings and prints, license a few images and occasionally teach a lesson or give a talk. My wife is a classical singer; between us, we make a decent living. There is a conventional wisdom that this is impossible, and I am happy to disprove it.

The second is that my artwork is improving over time. Most of the drawings visible on my website were drawn in the past three years; older drawings I am now mildly embarrassed to display, so obvious are their flaws to my eyes. I want to maintain this pace of artistic development so that in three years, I will be making significantly better drawings than I am making today. The one compliment that I most like to receive is: You’ve really gotten better.

What are the most common reactions to your works?

When I exhibit my artwork, there are four things that I am asked or told so often that I have ready answers for them:

1) Do you use a magnifying glass when you draw? No.

2) Where did you learn to do this? I studied art at Dartmouth College, but at the time I was not working on religious subjects, or in a medieval style. Most of what I know about these I taught myself later.

3) You must be exceptionally patient. Well, you can talk to my wife and kids; they will dispute that.

4) How is your eyesight? It’s pretty bad.

This article is courtesy of Ignitum Today.