I am one of the apparently few people who have seen There Be Dragons, Roland Joffe’s film about St. Josemaria Escriva, founder of Opus Dei. Only it isn’t really about Josemaria at all. It’s about Spain.

I am one of the apparently few people who have seen There Be Dragons, Roland Joffe’s film about St. Josemaria Escriva, founder of Opus Dei. Only it isn’t really about Josemaria at all. It’s about Spain.

The photography is beautiful and the settings are wonderful (so good that they made me homesick for Spain, where I lived in the 60’s and 70’s, in Pamplona and Madrid). Each individual piece is painstakingly well directed, and the actors do a good job with their one-dimensional characters (Derek Jacobi, Rodrigo Santoro, and Olga Kurylenko are standouts, and Charlie Cox does as well as can be expected with his Hallmark card lines). The problem is that there are too many pieces to this movie, each one is too lengthily and lovingly set up, and they are forced together artificially. The director really wanted not to tell a story about people, but to say something about history.

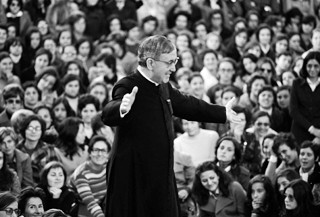

Opening with his death, the movie purports to be about Escriva, but his character is a talking holy card. It is structured around the relationship between him and childhood playmate Manolo, but there can be no relationship between a talking holy card and an antagonist with no position. It appears to be about the Civil War, but it is a poster-version of the war, with hackneyed and sanitized images of both sides, especially the left.

For a poster version hero, Rodrigo Santoro is superb as revolutionary leader Oriol, and Dougray Scott is good as the contemporary Robert, childless son of dying judge Manolo. Wes Bently fails to give reason or depth to his portrayal of Manolo, which makes sense, because Manolo makes no sense. He represents the evil secrets of the Civil War, the truth between the holy cards and the Communist posters. He is both sides, and no side. He is the Spain that, in the Franco era, became “the Judge” of what to say and when, keeping the war tightly under wraps. His repression and silence has made his son hate him.

The son, Robert, is modern Spain, cut off from its past and seeing no future (Spain has the lowest birthrate in Europe). The movie reveals New Spain to be the child of revolutionaries on both sides, while Manolo/Franco, the putative father, was simply a caretaker. The only continuity possible now between old and new Spain lies in finding and accepting the evil of the war, and realizing that your foster father’s only virtue was that he kept you alive so that you could do that.

Robert does not forgive his father for his evil; he simply accepts him for the good he did. Manolo submits to confessing his crimes, “kisses a–“, and is accepted by the spirit of Escriva as he dies. The movie can not work unless Manolo, the judge (Franco’s Spain), dies. That Spain, the one who betrayed the “real” Spain during the war, has no place in the future, a future toward which Robert is guided by his non-Western wife, who can peacefully absorb all conflict and transcend religions.

You might say that a movie can’t be such a simplistic allegory, and I would agree. That’s why this isn’t so much a movie, a story, as a thought piece using posters, holy cards, and scenery, with the action moved along by little bits of religiosity and coincidence. The character Josemaria was a convenient way to tie it all together. His Catholicism is on everybody’s side.

The truth is that Escriva was close to the Franco regime, and Opus Dei was at the heart of the Franco modernization of Spain. Perhaps the movie was Opus Dei’s attempt to distance itself from that past and re-brand itself for a new world. In any case, the movie was scared to scratch the surface of the war on either side. It is still a deadly topic in Spain. That, I think, is the code meaning of the title. There Be Dragons indeed, dragons which Spain still has not faced. And this movie doesn’t either.

(© 2011 Mary Ann Parks)