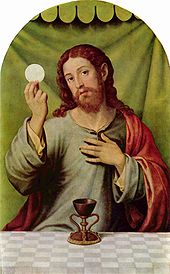

The Catholic Church teaches that in the Eucharist, the wafer and the wine really become the body and blood of Jesus Christ. Have you ever met anyone who finds this a bit hard to take?

The Catholic Church teaches that in the Eucharist, the wafer and the wine really become the body and blood of Jesus Christ. Have you ever met anyone who finds this a bit hard to take?

If so, you shouldn’t be surprised. When Jesus spoke about eating his flesh and drinking his blood in John 6, the response was less than enthusiastic. “How can this man give us his flesh to eat? (V 52). “This is a hard saying who can listen to it?” (V60). In fact so many of his disciples abandoned him that Jesus asked the twelve if they also planned to quit. Note that Jesus did not run after the deserters saying, “Come back! – I was just speaking metaphorically!”

It’s intriguing that one charge the pagan Romans lodged against Christians was that of cannibalism. Why? They heard that this sect met weekly to eat flesh and drink human blood. Did the early Christians say: “wait a minute, it’s only a symbol!”? Not at all. When explaining the Eucharist to the Emperor around 155AD, St. Justin did not mince his words: “For we do not receive these things as common bread or common drink; but as Jesus Christ our Savior being incarnate by God’s word took flesh and blood for our salvation, so also we have been taught that the food consecrated by the word of prayer which comes from him . . . is the flesh and blood of that incarnate Jesus.”

Not till the Middle Ages did theologians really try to explain how Christ’s body and blood became present in the Eucharist. After a few theologians got it wrong, St. Thomas Aquinas came along and offered an explanation that became classic. In all change that we normally observe, he teaches, appearances change, but deep down, the essence of a thing stays the same. Example: if, in a fit of mid-life crisis, I traded my mini-van for a Ferrari, abandoned my wife and kids to be a tanned beach bum, bleached and spiked my hair, buffed up at the gym, and made a trip to the plastic surgeon, I’d look a lot different. But for all my trouble, deep down I’d still substantially be the same confused, middle-aged dude as when I started.

St. Thomas said the Eucharist is the one change we encounter that is exactly the opposite. The appearances of bread and wine stay the same, but the very essence of these realities, which can’t be viewed by a microscope, is totally transformed. What starts as bread and wine becomes Christ’s body and blood. A handy word was coined to describe this unique change. Transformation of the “sub-stance”, what “stands-under” the surface, came to be called “transubstantiation.”

What makes this happen? The Spirit and the Word. After praying for the Holy Spirit to come (epiklesis), the priest, who stands in the place of Christ, repeats the words of the God-man: “This is my Body, This is my Blood.” Sounds like Genesis 1 to me: the mighty wind (read “Spirit”) whips over the surface of the water and God’s Word resounds. “Let there be light” and there was light. It is no harder to believe in the Eucharist than to believe in Creation.

But why did Jesus arrange for this transformation of bread and wine? Because he intended another kind of transformation. The bread and wine are transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ which are, in turn, meant to transform us. Ever hear the phrase: “you are what you eat?” The Lord desires us to be transformed from a motley crew of imperfect individuals into the Body of Christ, come to full stature.

Our evangelical brethren speak often of an intimate, personal relationship with Jesus. But I ask you, how much more personal and intimate than the Eucharist can you get? We receive the Lord’s body into our physical body that we may become him whom we receive!

Such an awesome gift deserves its own feast. And that’s why, back in the days of Thomas Aquinas and St. Francis of Assisi, the Pope decided to institute the Feast of Corpus Christi.