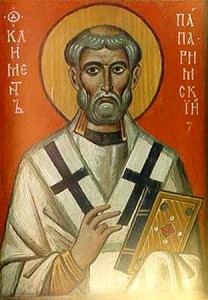

When beginning a consideration of the Church Fathers almost everyone will begin with Clement. Considered the second, third or fourth pope after Peter (depending on whose list you agree with), he marks the first post-apostolic writer whose text remains with the Church today.

When beginning a consideration of the Church Fathers almost everyone will begin with Clement. Considered the second, third or fourth pope after Peter (depending on whose list you agree with), he marks the first post-apostolic writer whose text remains with the Church today.

His identity is somewhat of a mystery running the range from the cousin of the emperor Domitian to a freed Jewish servant from a wealthy household. The only extant text we have of his is a letter to the Corinthians. There is a Second Letter to the Corinthians attributed to him but it has been widely discounted as his for many reasons, not the least of which is that it is neither a letter nor from Clement.

Clements first letter is an amazing read given this provenance. Clement was clearly a learned man and deeply immersed in the Old Testament as well as the surrounding culture. Most biographers will note his close connection to the apostles even finding that he was ordained by Peter himself to the office of Bishop. Others claim that he was the co-worker with Paul mentioned in Philippians 4. Whatever the case, when he writes, he is writes with authority and purpose reminiscent of Paul the Apostle and a Bishop of Rome.

The canonical letters from Paul to the Corinthians talk about troubles within the church at Corinth, factiousness and schism. Paul is trying to keep the Church together and not have it disintegrate into several small factions and rival churches. He stresses unity and simplicity as well as rallying around the teaching he has left them. Paul is being challenged by outsiders preaching a new gospel and he is quick to reprimand those in Corinth who abandon the faith he taught them. By the second letter to the Corinthians, Paul sees that persecution has befallen the church and some are struggling with the faith or abandoning it for old habits or safer practices.

Clement’s letter seems to pick right up where Paul left off although the situation has become considerably more grave. Young upstarts have overthrown the duly appointed Bishops and are taking control of the church consequently ripping it apart. “And so ‘the dishonored’ rose up ‘against those who were held in honor,’ those of no reputation against the notable, the stupid against the wise, ‘the young against their elders.’” (1Clem. 3.3, quoting Isaiah)

In response, Clements letter stresses unity and humility; the former being a product of the latter. The rebels need to humble themselves in the face of those who have been long in the faith. Each of the Bishops had been duly appointed and are deserving respect and obedience. This will bring about unity among the factions. “The humility and obedient submissiveness of so many and so famous heroes have improved not only us but our fathers before us, and all who have received His oracles in fear and sincerity.” (1Clem. 19.1)

Clement emphasizes how important it is for the flock to rally around the shepherd for the safety of both. The Church will fall if those appointed bishops are not held in high regard and obeyed. We do not get a complete idea of the grievances that lead to the overthrow but Clement knows that if he allows those who disagree with the Bishop to usurp that power, it will not stop with them. There will come along someone else who disagrees with what they say and split the church again. He will easily link their disobedience to the prideful disobedience of Adam and Eve.

He sees the overthrow of the local Bishop as on par with the murder of Abel by Cain and the hardness of heart of the Pharaoh in Egypt against Moses. He links their actions to the jealousy of Saul over David and the more recent persecutions of Peter and Paul by the jealous Roman authorities. He spends a great amount of effort demonstrating that the actions of a few in Corinth have grave consequences and the church must restore order.

Clements letter is a tour de force of Old Testament and non-Christian literature bringing in everything from the Genesis to the prophets as well as the story of the Phoenix rising out of the ashes. On this level alone it is worthy of study. On another level, though, we see the first post-Apostolic written evidence of the authority of the See of Rome. The very existence of the letter, the fact of it having ever been written, is significant; there is a certain underlying principle that allows the Church in Rome to admonish and advise the Church in Corinth. “So we too must intercede for any who have fallen into sin, that considerateness and humility may be granted to them and that they may submit, not to us, but to God’s will.” (1Clem. 56.1)

Only someone in the shoes of St. Peter would be so bold and then afterwards be held in such high regard. True, other letters have been written to other churches by those other than the successor of Peter but none have had the same authority as this letter enjoyed in the early Church. As late as the mid second century we still have some listing this letter, and not any other letter, among the canon of the New Testament.

Clements first letter is a fascinating transitional letter. It is not scripture but it is written at around the same time and shows how the early church began its post-Apostolic life. It gives us a glimpse of the troubles facing the early Church and the way in which those troubles were addressed. It plays upon the themes we find in many of the earliest writings, unity against schism, living the Christian life, and martyrdom. These are themes we will see in Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, and the letter to Diognetus. It is a great beginning to an age of apostolic zeal and humility in the face of persecution.

*Editor Note: Beginning today Catholic Lane will be launching a new series on the Church Fathers. Our goal is to help people gain not only a better understanding of these fathers, but to see if there is anything they can teach us about today’s problems.*