Everyone knows that religion is noble, and since no one in his right mind would possibly argue that liberty is not a precious right, it only stands to reason that “religious liberty,” as it is so often invoked these days, must be especially good!

Everyone knows that religion is noble, and since no one in his right mind would possibly argue that liberty is not a precious right, it only stands to reason that “religious liberty,” as it is so often invoked these days, must be especially good!

Now, it’s just a hunch mind you, but I suspect that this unspoken logical progression, or one close to it, is subliminally at play in tranquilizing the vast majority of otherwise inquisitive Catholics to the point where very few feel compelled to ask the critically important question, Was John Courtney Murray right?

Of course, it would help to know a little bit about who he is first.

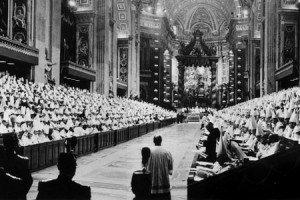

Once censured in the 1950’s by the Holy Office (as the “Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith” was known at the time) for his controversial writings on the subject of Church-State relations, the late American-born theologian, Fr. John Courtney Murray, S.J., is widely credited with being the primary author of the Second Vatican Council’s Declaration on Religious Liberty, Dignitatis Humanae.

This document is perhaps the single most controversial of all the conciliar texts for the simple reason that it represents what both critics and proponents alike consider a stark departure from the Church’s centuries old teaching that true religious freedom is the exclusive and Divinely instituted right of the Catholic Church alone, because only she has been commissioned by Christ, the very Word of God, to proclaim the fullness of truth.

Theologian Gregory Baum – a Council peritus who participated in the drafting of Dignitatis Humanae – pulled no punches in articulating the tremendous implications of this apparent doctrinal about-face in a 2005 interview with CNS.

“The Catholic Church had condemned religious freedom [as conceived by the Council]in the 19th century,” Baum stated, speculating that those bishops and theologians who resisted the Murray-inspired text did so because they “didn’t want to admit that the Church was wrong.”

He went on to portray the traditional teaching as maintaining, “Truth has all the rights and error has no rights.”

Summing up the contrasting opinion put forth by Murray, the same that prevailed at Vatican II, Baum concluded, “But, this is nonsense; truth is an abstract concept. People have rights.”

Already one may sense a fundamental flaw as “truth” is far more than just a concept; rather, it is the Person of Jesus Christ! But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Baum continued by pointing out, and accurately so, that the traditional teaching held that those who profess a non-Catholic creed (or what Pope Pius XI plainly identified as a “false religion”) could at best be tolerated in society.

At this point, it would helpful to take a closer look at religious liberty according to Tradition.

The Church has long held that man enjoys certain religious liberty on the individual level. This liberty is properly understood not as a “right to err” (which is entirely irreconcilable with the conviction that all rights come from the God who is truth; in whom no darkness dwells); but rather as a freedom from coercion.

This “right” brings with it, however, the solemn obligation to seek the “true religion” – that which Pope Leo XIII said “cannot be difficult to find if only it be sought with an earnest and unbiased mind; namely, the Catholic faith, the one established by Jesus Christ Himself, and which He committed to His Church to protect and to propagate” (cf. Immortale Dei 7).

The Church has long recognized that man, despite his best efforts, often does err in his quest for truth. Nonetheless, man’s ability to fall into error is no reason to defend the license to propagate religious falsehoods in the public arena, which not only represents an obstacle to others seeking the truth, but also an affront to Christ the King who reigns over all things and wills to draw all men to Himself through His Church.

It must also be noted that traditional Catholic doctrine has always made clear that it is the obligation of those who govern to exercise their authority in service to the one true King of all, Jesus Christ.

“No society can hold together unless some one be over all, directing all to strive earnestly for the common good, every body politic must have a ruling authority, and this authority, no less than society itself, has its source in nature, and has, consequently, God for its Author. Hence, it follows that all public power must proceed from God. Everything, without exception, must be subject to Him, and must serve Him, so that whosoever holds the right to govern holds it from one sole and single source, namely, God, the sovereign Ruler of all. ‘There is no power but from God’” (Immortale Dei 3).

Does this mean that government is absolutely required by Divine law to suppress false religions? No. Even as rulers of nations have consistently been called upon by the Church to exercise their governance in service to Christ the King in all things (at least prior to 1960 or so), she has also traditionally held that it is within the rights of rulers to tolerate false religious practices in public when a greater evil can thereby be averted in service to the common good.

This teaching does not go so far, however, as to give rulers free reign to adopt the tragic and demented attitude that all religions are essentially equals and should be treated thusly. Pope Leo XIII summed up the traditional doctrine as follows:

“The Church, indeed, deems it unlawful to place the various forms of divine worship on the same footing as the true religion, but does not, on that account, condemn those rulers who, for the sake of securing some great good or of hindering some great evil, allow patiently custom or usage to be a kind of sanction for each kind of religion having its place in the State. And, in fact, the Church is wont to take earnest heed that no one shall be forced to embrace the Catholic faith against his will, for, as St. Augustine wisely reminds us, ‘Man cannot believe otherwise than of his own will’” (Immortale Dei 36).

Having briefly considered the tradition of the Church on this matter, we will proceed in Part 2 to examine John Courtney Murray’s writings.