Under pressure of opposition, Catholic doctrine has usually developed out of necessity. For example, much of the Nicene Creed (AD 325) was a response to the threat from Arianism. Similarly, the Protestant Revolution prompted the Council of Trent to reform Catholicism.

Under pressure of opposition, Catholic doctrine has usually developed out of necessity. For example, much of the Nicene Creed (AD 325) was a response to the threat from Arianism. Similarly, the Protestant Revolution prompted the Council of Trent to reform Catholicism.

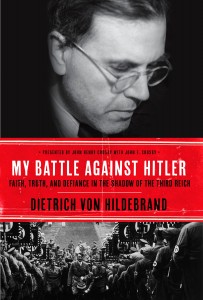

Likewise the pressures associated with a powerful regime of political oppression and overt evil may give rise to political / philosophical / theological thinkers like Dietrich von Hildebrand (1889-1977). His insights are relevant not just to the 1930s and ‘40s in Europe, but also to postmodern forms of oppression in the Western World today. Von Hildebrand’s book, My Battle Against Hitler (New York: Image, 2014) has now – ten years after the German language original – been translated into English.

Spurred by a government of criminals which had taken control of his German homeland in 1933, and imperiled by the infiltration of Nazism into neighboring Austria – the country of refuge for von Hildebrand and his family – he wrote essays and later composed memoirs about how Christian citizens can resist anti-Christian regimes. He worked tirelessly to bolster morale, urging his audiences and his readers to maintain an “absolute enmity” against the Antichrist in Bolshevism and in Nazism. Against the danger of being “morally blunted,” von Hildebrand warned about putting up “with the injustices of others and so accustom ourselves to a morally poisoned atmosphere;”[1] or of being paralyzed into inaction by the gaze which the serpent fixes upon its intended victims.[2]

Responding to Evil

Another Hildebrandian alert concerns clever tactics to deal with political setbacks; as distinguished from straightforward, soldierly resistance. Where the government is capable of exerting terrible pressure on believers, the temptation is toward wishful thinking or self-deception so as to avoid being confronted “with the alternative of either giving up everything or making compromises.”[3]

Similarly today, one hears artful proposals about escape routes, like defusing the confrontation over marriage by taking the state out of marriage entirely. The idea is to eliminate marriage licenses altogether, with only civil unions licensed. Supposedly this will let bakers and florists avoid the hard choices. The absurdity in this line of thinking is that the coalition which shoehorned same-sex-marriage into “the living Constitution” is not about to surrender the redefinition of marriage which they fought so hard to secure.

In Austria, especially after the Nazis assassinated the Chancellor, Engelbert Dollfuss (July 25, 1934), the policy of appeasing Hitler came to the fore, much to von Hildebrand’s chagrin. “One can only defend a fortress under siege by resisting any act of appeasement. The moment one begins coming to terms with an opponent,” insists von Hildebrand, “one has already begun to aid one’s enemy by throwing open the gates to the Trojan Horse.”[4]

What you never hear in von Hildebrand’s call to resistance are nuances ad nauseam about how we must love our enemies. All that is true enough, like the truism about hating the sin but loving the sinner. But during his five year exile to Vienna, with Austrian Nazis working feverishly for Anschuluss with Germany and submission of their national sovereignty to der Fuehrer; our soldier of Christ spent no time lacing his call for absolute enmity toward the Third Reich with hedging about how to demonstrate more love toward Nazi ideologues, and more charity toward anti-Semites. Everything in its season: “a time to love and a time to hate, a time for war and a time for peace.” (Ecclesiastes 3:8)

Von Hildebrand teaches us from philosophy and from experience how best to respond when the battle of worldviews goes terribly wrong, when even members of the clergy begin to flip flop under the influence of the Zeitgeist – of the intoxicating “spirit of the times.” Above all, says he, we must resist, and fight the good fight against a regime governed by Antichrist.[5]

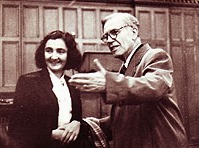

Such is our call in America today where concerted warfare is raging against God, against natural law, and against the written Constitution. It can be a very besieged feeling, a species of oppression, to be a cultural conservative in the USA. But von Hildebrand provides a kind of cross-chronological sense of solidarity, in that he and his wife endured worse trials; and yet in some ways their travails were similar to ours.

Personal Trials

Imagine being a native-born German, forced to see the advance of Hitler’s movement, the entrancement of fellow citizens, especially youth, infected by the excitement and contagion of it all. Envision his sense of helplessness as what he knew to be so wicked and wrong advanced inexorably from triumph to triumph. Imagine his fears in 1933 when forced to flee with his family, to leave behind his beautiful ancestral home in Munich, and to settle in a foreign country.

These traumas tempered by personal bravery are chronicled in “The Memoirs,” which comprise more than two-thirds of the Hildebrandian text. The remainder consists of contemporaneous essays written to resist the infiltration of Nazi paganism into Catholic Austria, combined with his less frequent references to the oppression of Soviet Communism, which was outside his personal experience. Of his some seventy essays devoted to ideological warfare against totalitarianism, fourteen are translated into English for this book. Seventeen pages of helpful biographical and historical information are provided by John Henry Crosby, the President of Hildebrand Project, headquartered at the Franciscan University of Steubenville in Ohio.

Five years after finding safe haven in Vienna, and working as professor of Philosophy at the University of Vienna, von Hildebrand and his wife, Gretchen, were forced to flee for their lives as the German military occupied Austria (March 1938). Barely escaping to safety in Switzerland and then to France, he had hardly settled into his teaching duties at the University of Toulouse when the Germans crossed the Maginot Line – like Attila and his Huns carrying all before them. Again on the run, with the Gestapo in hot pursuit (von Hildebrand was on Hitler’s short list for assassination) the family made it to Portugal, then to Brazil, and at last to New York City.

There at Fordham University – then still Catholic – he taught Philosophy from 1941-1960. Shortly after his retirement, von Hildebrand was compelled to see the coup d’etat against our Judeo-Christian Republic, as SCOTUS pushed religion out of the public square, beginning with public schools. And so the connection is not so distant after all, between us as witnesses to the overthrow of Christendom in the country of our birth, and to him as an émigré forced, as it were, to watch the Antichrist pursue him through Europe and across the Atlantic.

His passing in 1977 kept Dietrich from full realization of what would occur in his adopted homeland, including the “judicial putsch,” of 2015 (Justice Scalia’s phrase) seeking to mainstream hedonism into American culture by twisting the Constitution. Death spared Dietrich the scandal at Fordham, when Dr. Patrick Hornbeck, chair of the theology department, “married” his male partner in an Episcopalian liturgy.

But Alice von Hildebrand still lives, and by publishing the personal memoirs which her husband bequeathed to her, Alice has given beleaguered Western Civilization an invaluable reference point. The book provides many parallels to the challenges which confront us as Americans, or indeed threaten us as denizens of the formerly Christian West.

Soldier of Christ

Von Hildebrand writes as a soldier of Christ confronted by the two great tyrants of his time, Hitler and Stalin. Well before the Allied armies would confront Hitler’s forces during WW II, von Hildebrand waged war as an “intellectual officer” in the struggle of worldviews. As co-founder and editor-in-chief of Der Christliche Ständestaat (The Christian Corporative State) a weekly periodical published in Vienna, he was given, says von Hildebrand,

the chance to do battle with the Antichrist in Nazism and Bolshevism and to fight for an independent and Catholic Austria. As far as my task was concerned, I felt I was approaching a new and deeply meaningful life.[6]

The mixed results of his effort – it took outside military conquest to bring down Nazism – recalls Mother Teresa of Calcutta’s maxim that “what the Lord expects is not victory but fidelity.” Even if resistance within Germany, like Rev. Dietrich Bonheoffer’s, like the students in the White Rose Society, and like the dissenters in the Kreisau Circle, seem to have been fruitless; nonetheless their witness to future generations is redemptive, just as von Hildebrand’s memoirs and essays from the Nazi era show that not all Germans went with the flow of the Zeitgeist, or chose to remain quiescent.

His witness is not only redemptive as regards Germany’s past, but instructive as to possible courses of action today. As Mary Ann Glendon[7] puts it:

At this moment in history, no memoir could be more timely than Dietrich von Hildebrand’s account of how and why he risked everything to witness against the spreading evil of National Socialism. With much of today’s world silent as Christians face increasing persecution, many good men and women are asking themselves what they can do. This remarkable book will challenge and inspire them.

His writings also carry theological authority, as testified to by Popes who knew him, including his friend, Pius XII, who lauded him as “the 20th Century Doctor of the Church.” St. John Paul II called von Hildebrand, “one of the great ethicists of the twentieth century;” and Pope Benedict XVI said this:

the intellectual history of the Catholic Church in the twentieth century is written, the name of Dietrich von Hildebrand will be most prominent among the figures of our time.

Anti-Anschuluss

Another aspect of Von Hildebrand’s thought is his negation of nationalism, which he critiques both directly (as will be seen), and obliquely in the context of disunion. For four reasons, von Hildebrand opposes Anschuluss – the union of Austria with its larger German speaking neighbor. First, Austria “embodies the noblest and most authentic development of the German spirit.” Second, Austria was called in 1933-1938 to a great mission, “to be an outright repudiation of nationalism.” Third, Austria “is not a mere branch of the German nation, nor a mere portion of the German cultural sphere.” It “constitutes a cultural space all its own, a totally unique form of German character that differs as greatly from Germany as America does from England.”

And fourth, the more general principle: “a national bond of unity is not the only factor that contributes to the formation of a thriving state.” On the contrary, “in order to be able to develop fully, it may make sense for certain nations to be present in several states.”[8]

So too in America today: disunion may make a lot more sense than national borders enclosing a people polarized on a host of issues – from the sacredness of marriage, to secularism, to the meaning of “truth,” to the sanctity of life, to whether or not religious liberty should trump sexual freedoms. National divorce may well be preferable to prolonging the 50 State Union of two camps: enemies of Christian Western culture and those who still hold fast (in greatly varying degrees) “to the foundations of the Christian West in a moral, legal, sociological, and cultural sense.” When, as von Hildebrand puts it, “the question of truth as such is suppressed in favor of a purely subjective factor,” when “the truth or falsity of a worldview … is deposed from its seat of judgment,” [9] then with St. Paul we can ask (2 Corinthians 6:15), “what concord hath Christ with Belial? or what part hath he that believeth with an infidel?”

“Moderatation”

Another theme in von Hildebrand’s thought is his sense that so called “moderate elements” within National Socialism were “the most dangerous,” as compared to the influence of militant Nazis. In a private audience with Cardinal Pacelli – then Secretary of State in the Vatican, later Pope Pius XII – von Hildebrand convinced the Cardinal that no bridge was possible between Christianity and anti-semitism which was not only theologically and morally wrong, but utterly contrary to nature.[10] They agreed that Alfred Rosenberg, the Nazis’ major theoretician, did less harm than moderates who confuse Catholics by concealing their true dispositions, who secretly or inadvertently side with the Antichrist. Compared to the more reasonable sounding moderates, there is less danger from the militants who “drop their masks and openly reveal the absolute incompatibility of Nazism with Christian faith.”[11]

Likewise in America during an earlier era, Thomas Paine contended against those who would rather reconcile with King George than fight the Redcoats, and he singled out moderates as most likely to bring calamity upon the American cause (Common Sense 1776). So too today, where our radical problems call for radical solutions: “moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.”[12]

Von Hildebrand was also pained by the tepid response of the Catholic clergy. (In a perverse sort of way it is reassuring that this phenomenon within the Church is not unique to our own age). The Concordat of July 1933 between the Vatican and Hitler’s then half-year old government, “as well as the stance of the German bishops and also of some German theologians, contributed to concealing the abyss that separates National Socialism and Christendom.” Von Hildebrand lamented that the Church failed to seize the opportunity, “a moment in which millions of Protestants and Socialists would have converted had the bishops in Germany spoken a completely uncompromising ‘non possumus’ toward National Socialism, … had they called its crimes by name, had they uttered a total anathema.”[13]

Likewise today; if the USCCB would withdraw the Catholic Church from secular marriage altogether, and confine the clergy to Matrimony as a sacrament, and if the Bishops would excommunicate the likes of Nancy Pelosi, Joe Biden, Anthony Kennedy and other “Catholic” politicians / judges who promote the culture of death. Such radical responses might hearten loyal Catholics, and draw into the Church many Americans who are looking for tough resistance to resurgent paganism.

Nationalism versus Patriotism

Particularly applicable to apostate America with all its pride and militarism is von Hildebrand’s distinction between genuine patriotism and nationalism. Nationalism is, in his view, the deification of a nation, rendering it an idol. Nationalism is as different from patriotism “as the true, divinely ordained love of self is from egoistic self-love.” Patriotism loves the “divine idea” which one’s particular country represents, and to the extent that one’s government contradicts that ideam divinam, it betrays what is “great and noble” in the national heritage.[14] Furthermore, insofar as the people themselves demonstrate “collective egoism” they are in reality “incapable of truly loving” their own country; they show “an inferior and impure love.”[15]

No amount of sacrifices made on behalf of the nation in a time of war can in any way change this. The nationalist is incapable of genuine love, for love of a good is always genuine only to the extent that it participates in the love with which God loves it.[16]

Thus von Hildebrand was able in good conscience to root for the Allies to win both World Wars, (doing so secretly as a German soldier in WW I).[17] “The heresy of nationalism” constitutes a “ terrible error,” making natural love of country into a “perversion.” It culminates, says von Hildebrand, “when the nation is ranked above the highest community of them all, namely the supernatural community of the Church understood as the mystical body of Christ.”[18]

Along these lines, I would argue that by disavowing “the laws of nature and of nature’s God” – expressely stated in the Declaration of Independence – SCOTUS has, in the 2015 same-sex-marriage decision, undermined an original principle of the United States dating from its founding, and has forfeited the nation’s right to a place “among the powers of the earth.” Thus the true patriot has deeper and potentially opposing loyalties relative to postmodern America than are held by strident nationalists.

Von Hildebrand continues:

Nationalists never see the true values of their nation, its cultural nobility, or the deeper significance of its national genius. All they see is its power, its gloire, its political influence. The decisive point, which makes the nationalist’s breast swell with pride, is not the sublimity of his culture, but the number of square kilometers in his country and the size of its army.

Such a citizen loves the American empire of the 21st century. And the rainbow nationalists among us are delighted to see this same empire use military, economic, and cultural superpower to pressure Third World countries, pushing them toward the anti-Christian values of the West.

___

In conclusion, Dietrich von Hildebrand’s opposition to the Nazi regime should boost morale among cultural conservatives in the apostate West. His personal sense of isolation in fighting the Antichrist, compared with his nationalistic contemporaries in Germany and Austria,[19] reassures us that we who resist postmodern values boldly are not so isolated after all. For we have a noble and articulate soul mate from a not so distant era. Furthermore, von Hildebrand’s bravery against a regime hell-bent to murder him, should strengthen our own resolve to be Christ-like in relation to the postmodern West, i.e. to stand forth regardless of the risk, as a “sign of contradiction.”[20]

_______

[1] Dietrich von Hildebrand, My Battle Against Hitler: Faith, Truth, and Defiance in the Shadow of the Third Reich, tr. & ed. by John Henry Crosby with John F. Crosby (New York: Image, 2014), p. 260.

[2] “There is a moment when intimidation and paralysis set in to such a degree that one becomes passive in the face of something harmful,…” Ibid., p. 51.

[3]Ibid, pp. 78-79.

[4] Ibid, p. 213.

[5] Ibid. p. 83.

[6] Ibid, pp. 108-09.

[7] Mary Ann Glendon, Harvard Law Professor; US Ambassador to the Vatican, 2008-09.

[8] Von Hildebrand, My Battle Against Hitler, pp. 250-51.

[9] Ibid, pp., 294-95

[10] Ibid, p. 278. Von Hildebrand (who was not himself Jewish) describes anti-Jewish edicts by the government as “an attack on human nature… a direct attack against the incarnate God, against human nature sanctified by the Incarnation.”

[11] Ibid, p. 184.

[12] “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” Barry Goldwater, Presidential nomination acceptance speech, July 16, 1964.

[13] Von Hildebrand, My Battle Against Hitler, pp 169, 183; cf. 79.

[14] Ibid. pp. 93-94.

[15] Ibid, pp. 248-49.

[16] Ibid, p. 251.

[17] Ibid, p. 11.

[18] Ibid, pp 249-50.

[19] Ibid, pp. 76-77.

[20] The Gospel According to St. Luke 2:34.