When God created Adam and Eve, he placed them in a garden and blessed them. He told them, “Be fertile and multiply; fill the earth and subdue it. Have dominion over the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, and all living things that move on the earth” (Gen 1:28). The Catholic Church has long understood this passage both as a reference to man’s unique stewardship over nature and a justification for the pursuits of science.

When God created Adam and Eve, he placed them in a garden and blessed them. He told them, “Be fertile and multiply; fill the earth and subdue it. Have dominion over the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, and all living things that move on the earth” (Gen 1:28). The Catholic Church has long understood this passage both as a reference to man’s unique stewardship over nature and a justification for the pursuits of science.

The Church is not nor has it ever been antagonistic to scientific and medical progress per se. Indeed, more and more historians are analyzing the unique contribution that the Christian emphasis on human reason has made to the development of the arts and sciences in Western culture. Even the stereotypical blight on that record — the Galileo controversy — is now recognized to be much more complicated than what most of us learned in high school.

Though the Church is not against scientific and biomedical advancement, she nonetheless routinely challenges scientists and doctors with her teaching, which is itself grounded in faith and reason. The reason the Church’s teaching role is important in bioethics is that science is not morally neutral. This news may come as a surprise to many since science and medicine purport to be objective disciplines.

In his encyclical, Saved in Hope, Pope Benedict XVI recounts the history of the scientific movement, tracing it back to Francis Bacon and the seventeenth century. With the excitement of New World and a spate of scientific discoveries, a new era emerged. The basis of this new era was “the new correlation of experiment and method that enables man to arrive at an interpretation of nature in conformity with its laws and thus fully to achieve ‘the triumph of art over nature’” (no. 16). But like any other human endeavor, the presuppositions of science and medicine carry the moral baggage of their practitioners. For all the progress and advancement we have achieved in the subsequent centuries, we have also seen our fair share of the destruction of human life in the name of that progress. No matter the promises offered, science cannot employ any means whatsoever to achieve its desired goals.

Pope Benedict, like Pope John Paul II before him, recognizes the incipient temptation of science to reduce the human person to yet another material object to be analyzed, experimented upon, and manipulated according to the empirical method. Science cannot offer us the meaning of life and it cannot reveal to us the dignity of the human person. Human reason is always confronted by its limitations when faced with these questions. In our zeal for scientific accomplishment and medical progress, we can be blind to this fact.

In the Catholic tradition, faith heals reason, purifies it, and reinforces it. There is no opposition between the two. Pope Benedict spoke eloquently of this in God is Love, his first encyclical. He wrote, “Faith by its specific nature is an encounter with the living God-an encounter opening up new horizons extending beyond the sphere of reason. But it is also a purifying force for reason itself. From God’s standpoint, faith liberates reason from its blind spots and therefore helps it to be ever more fully itself” (no. 28).

This, then, is the role that Church teaching plays in bioethics. The teaching of the Church, grounded in the revelation of Jesus Christ, testifies to the dignity of the human person against any and all procedures that treat men, women, and children as mere means to human progress. When the Church addresses bioethical issues, she is guided by a few basic principles

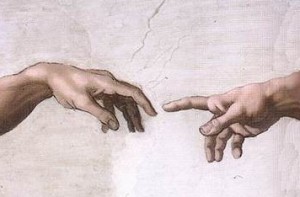

First, man has a unique dignity above all other creatures on earth. As the Second Vatican Council taught, man is the only creature created by God “for its own sake” (Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, no. 24). Man’s unique status is the result of his being created in the image and likeness of God (Gen 1:27), on the one hand, and called to communion with him, on the other.

Second, God is the Lord and author of life. He alone gives the gift of life. Every person has the right to accept that gift. Every man, woman, and child has a fundamental right to life.

Finally, contrary to popular opinion, the human body is no mere shell or collection of cells and organs to use as we please. Neither is the human person reducible to the outward appearance of the body. Rather, Catholics believe that the human person is a holistic composite of body and soul. Both are intricate principles of the human being. What happens to either affects the person in some way — whether it be sin in the soul or genetic modification of the body. Try as we might, we are not indifferent to either.

The Church always works to remind men and women of their inherent dignity and moral responsibility as children of God. While applauding the advancement of science and medicine at the service of the human person, she does not remain silent when that dignity is forgotten. While she respects the authority scientists and doctors have in their own field, the Church will always warn against research that dismisses human dignity. As promising as stem cell therapies are, for example, we cannot tolerate those forms of research that destroy human life in its earliest stages to acquire those stem cells. It would be contrary to the dignity of the human person to do so.

In Saved in Hope, the pope cautioned, “If technical progress is not matched by corresponding progress in man’s ethical formation, in man’s inner growth, then it is not progress at all, but a threat for man and the world” (no. 22). The Church’s mission in bioethics is thus no different than her mission to the world, which is the spread the Gospel-the message of who we are and who we are called to be in Christ.

(© Fr. Thomas Petri O.P.)