When discussing the Catholic priesthood, many questions need to be considered. First and foremost, we must ask ourselves where the idea of the priesthood comes from in the Scriptures. Contrary to the ideas of our Protestant brethren, the idea of the ministerial priesthood is clearly enunciated within the New Testament. Indeed, if there is no priesthood, there is no Christian faith.

When discussing the Catholic priesthood, many questions need to be considered. First and foremost, we must ask ourselves where the idea of the priesthood comes from in the Scriptures. Contrary to the ideas of our Protestant brethren, the idea of the ministerial priesthood is clearly enunciated within the New Testament. Indeed, if there is no priesthood, there is no Christian faith.

It will not suffice to simply say that only Christ is a priest. Christ is understood as our true high priest. On this, anyone deserving the name of Christian agrees. Equally unsatisfying is the statement that we are all priests. Now the Bible certainly teaches that all who call upon the name of the Lord are priests. First Israel, and then the New Testament community are referred to frequently as a “royal priesthood, a holy nation.” Yet the priesthood of Jesus Christ and the Catholic priesthood go far deeper. In the Epistle to the Hebrews, the author frequently makes reference to Christ being a priest “of the order of Melchizedek.”

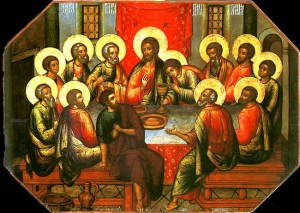

For all intents and purposes, Melchizedek is a very obscure figure in the Old Testament. He appears only once in the book of Genesis. He is viewed as the King Salem, and “without father or mother,” which is merely a literary device to signify his timelessness. His offering, rather than animals or the first fruits of ones labor (something going back to the very beginning of creation), were bread and wine. While the Israelites of the Old Testament had their priests of the Levitical law, they had nobody of the order of Melchizedek. Instead, they looked forward to the day of the Messiah, who the Psalmist makes clear will be a priest of the Order of Melchizedek. That Messiah came in the person of Jesus Christ. Yet we must ask ourselves: does anyone else belong to this priesthood? The Biblical evidence provides a resounding yes. To do that, one must simply look at what is popularly known as the “Last Supper.”

When considering the audience of the Last Supper, a few things come to mind. First and foremost is that not all of Christ’s followers were present. Only the Apostles were present in that room. The second consideration is that the text of the Last Supper is absolutely filled with sacrificial terminology. We see Christ “giving thanks” for the bread and wine.

This in and of itself denotes a sacrifice. Christ then says that the bread is His body, “given” for you. The word implies authority. When the Devil tempts Christ in Matthews Gospel (Matt 4:9), Satan states he will “give” all the Kingdoms of the Earth to Christ in exchange for His worship. Yet for Christ, His body is “given” for the sake of the Apostles. Who is it given to? Would it make sense for Christ to give the Apostles His body, as the purpose of the offering? No, the offering is given to God for their sake. Right in those words, we see a connotation of sacrifice.

The second aspect of sacrifice is present during the offering of the wine. Christ calls the wine “the cup of my blood, the new testament.” Another way of understanding testament is covenant. A covenant is an agreement between two parties. In the Bible, the covenant is the definition of a relationship between God and man. We have numerous examples of covenants in the Old Testament. In every instance, they are ratified by a sacrifice. The writer to the Hebrews makes this clear. (Hebrews 9:15-20.) Christ’s blood contained in the chalice (cup) is that which ratifies the New Covenant. Whereas before the blood of bulls and goats ratified the covenant, now Christ’s blood ratifies it. The blood of the New Covenant is described in many translations as being “shed” unto many.

The word “shed” does not really capture the entire significance of what is mentioned. Far better is the understanding that the blood is “poured out” upon something. When Cain shed the blood of Abel, his blood was poured out on the earth, When the sacrifices were offered in the law, the blood was poured out upon the altar, and sometimes even sprinkled upon the faithful. Blood is viewed as something with incredible power in the Bible. Blood can cleanse one from the sins, but the innocent blood shed serves as a constant reminder of the sin, as the blood of Abel demonstrates. If the blood is “poured out” it implies that this is not done voluntarily by the one being offered. Christ did not slash his wrist, and then His blood was sufficient. No, Christ’s blood was poured out upon the altar of the Cross in his crucifixion, just as the blood of bulls and goats was forcibly poured out upon the altar when they were killed.

Another instance of the sacrificial terminology comes from a simple command. After the offering of the cup (or in some cases the offering of the bread), Christ issues the command that the Apostles are to “do this in remembrance of me.” We find this in Genesis 22, where the angel commands Abraham not to “do” the thing Abraham had planned to do to Isaac. What was he to do? He was to sacrifice his son as an offering to God. In Exodus 22:29-30, the commanding of offering of oxen in sacrifice is given, and we are told that they should “do” likewise as was mentioned in verse 29. Verse 29 talks of offering sacrifice. Through the offering of that sacrifice, the individual is made holy unto God, and a certain code of conduct is expected of him. When the prohibition against idolatry is given, the Israelite is warned not to “do” the works of the false gods. This is clearly an understanding that one is not to offer sacrifice to an idol. When discussing the activities of Aaron in his priesthood atoning for sin, the Jews are told to “do” likewise for the tabernacle. (Leviticus 16:16.) The context demands an understanding of sacrifice. (Also Leviticus 21:6.) Numbers 8:19 confirms this, when the successors of Aaron are made priests to “do the service of the children of Israel.” The service they are doing is clearly that of a sacrifice.

From these words, it is clear that Christ is telling his Apostles to offer sacrifice. Yet what kind of sacrifice? The sacrifice is to be a “remembrance” of Christ. Now when we hear “remember”, we simply think of “recalling.” To the ears of the Hebrew, the word means something much more. When they celebrated the Passover, it was indeed a “memorial” sacrifice. Yet in every step of the Passover, they entered into the Exodus from Egypt. That Exodus from Egypt likewise symbolized their own Exodus from the world to be with God for eternity. When God passes judgment on Amalek, he does so in the term of “remembrance.” Is this a mere memory of a past event? The Hebrew word for “remembrance” is zeker. The Greek word for zeker is anamnesis, the same word used in the New Testament. Exodus 17 states:

And the Lord said to Moses: Write this for a memorial in a book, and deliver it to the ears of Joshua: for I will destroy the memory (zeker) of Amalek from under heaven. And Moses built an altar: and called the name thereof, The Lord my exaltation, saying: Because the hand of the throne of the Lord, and the war of the Lord shall be against Amalek, from generation to generation.

When the memory of the act is recalled, the judgement of God is renewed. There would always be war with Amalek. When they passed by the altar established, they were to remember that because of Amalek’s wickedness, the Lord would always be against him. When the woman of Zaperath lost her son, she cried out to Elijah that his presence would cause a “remembrance” of her sins, and cause the death of her son. Clearly, in the Old Testament, the act of “remembrance” has an immediate effect: as a result of the remembrance, something happens.

Now that we have these things established, we can better understand the words of Christ. When he says “do this in remembrance” of me, he tells the Apostles “Offer this sacrifice of bread and wine, which is my body and blood. Every time you offer this in remembrance, the body and blood is offered for your sake.” It is for precisely this reason that Christ is portrayed in Revelation as a lamb “standing as if slain.” The offering of bread and wine brings to mind the sacrifice of Melchizedek. Yet Christ’s sacrifice, though like Melchizedek, goes beyond it in being the fulfillment of that sacrifice. We also know that while this offering occurred once for all on the cross, it happens throughout the world. The prophet Malachi speaks of how life will be under the New Covenant:

For from the rising of the sun even unto the going down of the same my name [shall be]great among the Gentiles; and in every place incense [shall be]offered unto my name, and a pure offering: for my name [shall be]great among the heathen, saith the LORD of hosts.

Malachi speaks of the Gentiles offering a pure offering which is accepted by God, and that offering happening continually. Yet in the New Testament, only the offering of Christ is accepted. Only the offering of Christ is pure. Yet we know that the Gentiles will offer this pure offering in the New Covenant. Only through the Eucharist is this accomplished. Yet how is this a “remembrance?” When Christ spoke in the Last Supper, the offering was clearly to cleanse the sins of mankind. When we offer the Mass in memorial of that offering, we not only recall the offering Christ offered in that room, but the very effect of that offering comes about. Just as Christ made the bread and wine His body and blood, so does the priest during Mass. Just as the original sacrifice cleansed the world from the sins committed, every offering of the Mass cleanses the faithful from their sins committed. The biblical evidence is overwhelming. Those who wish to believe the Bible must believe what the Catholic Church teaches about the priesthood.