Eve Tushnet is among the most promising young Catholic intellectuals in America. She is a student of art and culture whose writing touches on sexuality, personhood, and faith. Published in journals secular and religious, she was profiled in the New York Times as a “gay Catholic voice against same-sex marriage.” This is the first of four essays on friendship as a Christian vocation.

Every form of love between humans must eventually reconcile itself to death. More than erotic love, spousal love, filial love, or love of neighbor, the love between friends in Western art and culture has been stalked by the shadow of death. The death of the friend has spurred poetry, theology, painting, history, even schools of spirituality. It is striking that almost all of the greatest art and writing about friendship was created to remember kindred souls departed for the world beyond our own.

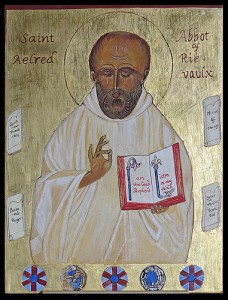

Andrew Sullivan’s flawed but valuable essay “If Love Were All” explains: “One of the greatest poetic expressions of friendship, perhaps, is Tennyson’s ‘In Memoriam.’ The deepest essay, Montaigne’s, was written about a friend who had been wrenched bitterly away from the author at an early age. Cicero’s classic dialogue on the subject was written in honor of a dead friend; so was the most luminescent medieval work, Aelred of Rielvaux’s De Spirituali Amicitia. Augustine’s spasms of grief at the death of a friend is the first time he ever really expressed the friendship he once felt, rather than simply feeling it.”

Along with memorials on paper come memorials in stone; along with memorials in poetry come memorials in prayer. As Alan Bray writes in the introduction to The Friend, his 2003 study of friendship in England from about the year 1000 through the death of Cardinal John Henry Newman, “Nearly twenty years ago, I visited Cambridge to give a lecture. As I was finishing breakfast in college the morning after my lecture, I was joined by my host Jonathan Walters, then a graduate student in the university. We walked to the chapel of Christ’s College, where we looked at the seventeenth-century monument by the communion table that marks the burial in the same tomb of John Finch and Thomas Baines. ‘What,’ I was asked, ‘do you make of this?’ This book is a long-delayed reply to that question.” The Friend reveals the strong and often curious ties that hold together kindred souls even after death: shared crypts; bittersweet ballads; memorial Masses; the adoption of orphaned children. In these ways and more, friendship persists beyond the grave, for “love is strong as death” (Song of Solomon 8:6).

Exploring the connection between death and friendship can give a greater sense of what the relationship means: its depth and its characteristic joys and crosses. The Catholic writer Mark Shea has called friendship “the forgotten love.” Perhaps by looking at its memorial art we can rediscover and remember not only the friends themselves, but the nature of their love.

Friendship does not produce offspring. If the next generation is in some way a sign of hope or a protest in the teeth of death, friends must find other ways to express hope and protest. A bereaved parent can see strange reflections of a spouse’s countenance in the face of a child. The result of their love is as obvious as a soiled diaper, as subtle as the quirk of an eyebrow.

And so friends must find other ways to make evident the fact that their love also triumphs over death, and that the project of that love does not end with burial. Marsden Hartley’s anguished painting memorializing Hart Crane makes their friendship tangible, sends it out into the world to have effects beyond the emotions he kept to himself. For St. Aelred, who described the practice of true Christian friendship as a project of spiritual transformation, making both partners more Christlike as they together seek to imitate Jesus’ sacrificial love, the project of a friendship is not complete until it has brought both friends to Heaven and into full communion with God. This kind of love is more than a two-person matter. There is no room for folie a deux. When love is a vocation, not merely an emotion or a season of the heart, it flows outward and transforms not only those who love and are loved, but those around them. The Holy Spirit proceeds from the love between the Father and the Son; children, typically, result from the love of husband and wife; what flows forth from the love between friends? Perhaps the art, theology, and memorials of friendship are one answer. Aelred used the memory of his late beloved Ivo to instruct the living monks who sought his counsel. He honored Ivo through this teaching and through his writing. It is as if the monks—and the readers of De Spirituali Amicitia down the centuries—have become spiritual children of these two men, taught and shaped by them, honoring them and bringing their love forward into the future.

Sullivan’s aforementioned essay offers other possible explanations, some more persuasive than others. He notes the consistent link between friendship and grief. I am not really persuaded by his idea that “there’s something about friendship that lends itself to reticence,” so that the silence in which the acts of friendship are naturally performed is only broken by the cry of the mourner. This seems like, for one thing, an overly masculine take on friendship. Women friends are not typically shy about claiming one another: describing, naming, discussing, even dissecting their bonds. Moreover, the friends whose relationships are described in Bray’s study did make their friendships public, often taking public vows of friendship and creating kin networks based on those bonds. A public vow, though it may serve as a modest veil for the tenderest emotions of the heart, is more or less the opposite of reticence.

More persuasive is Sullivan’s analysis of friendship as a relationship between equals. “It is only, perhaps, when you absorb the notion that someone is truly your equal, truly interchangeable with you, that the death of another makes mortality real,” he writes. Equality and similarity are elements of friendship that are absent from filial love (which stems from and adorns inherently unequal and hierarchical relationships) and erotic love (which is fueled by dissimilarity, and may even be defined as the desire for union with one who nonetheless remains irreducibly different). The natural equality of friendship might explain why the death of a friend is so shocking: it serves as clear foreshadowing of one’s own death. The friend shares our way of life—our interests, our social position, our addictions, our vocation. We are yoked side-by-side and our role in love is the same, unlike such pairs as parents-and-child or husband-and-wife. And so both the fact of the friend’s death and the manner of that death makes it glaringly obvious that, since we similarly lived, we will also similarly die.

Modernity added a few new elements to the connection between death and friendship. Sullivan writes about friendship as a possible solace for the loneliness of modern life. Certainly modern life has exalted erotic and familial love, narrowing our focus so that these are almost the only kinds of love we can still understand or long for. This has made it much harder to acknowledge the love and grief of friends. Perhaps one reason for the intertwining of friendship, mourning, and homosexuality in modern art is that both gay partners and devoted friends have so often been treated as strangers at the sickbed or the graveside. They have been the undesignated mourners. A mourner needs a voice, some way of making his anguish public, and many of these unacknowledged mourners have found outlets in art, music, and literature — compensation for the public voice they were denied at funerals, wakes, and burials.

There are many other reasons for the insistent historical connection between death and friendship. Over the next few months, I will explore different manifestations of the death-haunted art of friendship, from medieval monks to California punks, from Ivy League preps to meth lab freaks, always with an eye toward recovering an understanding of friendship as a Christian vocation.