In Handle with Care, Picoult refers to a “language of loss” that parents and children endure in the most intimate family relationships. Within adoptive families, these losses can be especially complex — if for no other reason, because of the number of people involved in the family bond.

In Handle with Care, Picoult refers to a “language of loss” that parents and children endure in the most intimate family relationships. Within adoptive families, these losses can be especially complex — if for no other reason, because of the number of people involved in the family bond.

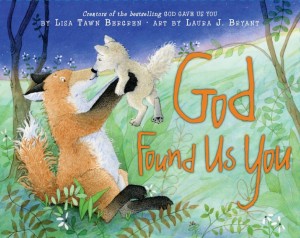

As parents, however, we must be willing to see – and help them articulate – the pain of our children as it surfaces. Sometimes the expressions of grief will surface at unexpected times. For example, the other day I was reading my children a book entitled God Found Us You,by Lisa Bergren and Laura Bryant (HarperCollins).

This happy, gentle story about a mother fox and her adopted baby fox, who asks her to tell him the story of how he came to be with her. The kind of books adoptive parents love, because it ties up the future in a lovely, reassuring bow. We read it to our children, hoping it will give them the feelings of love and security we so much want them to have.

The first I read this book to my kids, however, their reaction was mixed. While they want — and need — the reassurance of my love for them (just as Mama Fox reassures her little one), the book also brought some unsettling feelings to the surface.

“It is those who have been most deeply wounded by grief that have the greatest capacity for joy.” I can’t recall where I heard this bit of wisdom, but it seems to fit here. We cannot “fix” or wipe away the pain, cannot silence this language of loss. But if we are doing our job as parents, our children will find in us the compassion they need to make sense of their world.