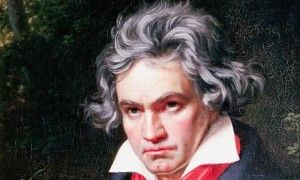

I keep a bust of Ludwig van Beethoven on the fireplace mantle in my home. It reminds me of the human capacity to overcome adversity to achieve great things. When I doubt myself in my own acquired disability of multiple sclerosis, I listen to Beethoven — particularly his 9th symphony — written in total deafness, but at the peak of his creative prowess.

I keep a bust of Ludwig van Beethoven on the fireplace mantle in my home. It reminds me of the human capacity to overcome adversity to achieve great things. When I doubt myself in my own acquired disability of multiple sclerosis, I listen to Beethoven — particularly his 9th symphony — written in total deafness, but at the peak of his creative prowess.

In his 9th symphony I detect a triumph of human spirit over adversity, sustained by a spark of God’s love in a silent world. Although Beethoven used Schiller’s Ode to Joy, there is a spirituality or mystical quality to Beethoven’s 9thSymphony. It carries a note of authentic life experience. It contains great energy yet a peace and acceptance won by strife, and a wisdom only suffering can teach. To me, it illustrates how our loving God can reach into the silent world of a deaf genius and touch us even 190 years later.

Most people are aware that Beethoven was deaf when he wrote his 9th Symphony; it was his crowning achievement. But I want to bring your attention to the fact that Beethoven was going deaf when he wrote his 1st symphony. It was detectable when he began composing it in 1798, and when it was completed in 1800, Beethoven had become quite anxious about his malady. By his own words, Beethoven had noticed his hearing loss beginning in 1796 at the age of 26. By 1801 his physicians began various therapies, to no avail. His deafness increased to become near total, yet his creative prowess never faltered.

All nine symphonies were composed with some level of deafness! His mind was so muscular. How could it be that the standard bearer of the Romantic era was a deaf composer? Despite this, Beethoven rose above his predicament to reach unequalled human achievement. His beloved Moon Light Sonata was composed in serious deafness. The same is true for his opera Fidelio, and Creatures of Prometheus. It is doubtful he heard much of his 5th Symphony, his concerto for violin and orchestra or his Masses.

In Beethoven’s life story, we read about his inner and outer grief, his disappointment with life, his isolation and emptiness brought on by his disability.

Beethoven addressed this isolation himself in a letter he wrote to his brother Karl in 1802.

“[F]orgive me when you see me draw back….for me there is no relaxation with my fellow man, no refined conversations, no mutual exchange of ideas. I must live almost alone, like one who has been banished. …But what a humiliation for me when someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone standing next to me heard a shepherd singing and again I heard nothing. Such incidents drove me almost to despair; a little more of that and I would have ended my life – it was only my art that held me back.”

In that same letter, Beethoven prayed, “O Divine One, thou seest my inmost soul thou knowest that therein dwells the love of mankind and a desire to do good.” At the end of his letter to Karl he wrote in his despair, “Farewell and do not wholly forget me when I am dead.”

These words were written at a crisis point for Beethoven about his increasing disability. Happily for us, his crisis passed and the great man rose above his deafness to eventually write his 9th and final symphony at his height of creative power.

Throughout more than 30 years with degenerative MS, I have observed and studied grief – both my own and others. It is my experience that grief is diverse yet distinct. People grieve in various ways. They grieve visually, in sound and abstract ways. Perhaps grief rises at the sight of a lake, a flower or a certain café that reminds the griever of happier days before sickness or disability. A particular song may transport the griever to another time or place.

Grief is distinct in that it is focused on an object. Grief is often dynamic because it still interacts to its surroundings and stimulus. Healthy grieving is expressive. Grief can express a multitude of emotions through music, writing, drama or even dance. This is good. It indicates grief that is fluid and moving. As long as grief is moving and expressive the griever is likely to emerge spiritually matured. If it ceases to move, it may stagnate and settle into depression. (Depression tends to turns in on itself focusing of the darkness of the griever’s soul.)

Grief will come to every life. Surrender your anguish to God’s love to use as a vehicle for spiritual growth. The 17th Century Christian Poet, John Donne, wrote: “No man hath affliction enough that is not matured, and ripened by it, and made fit for God by that affliction.” Having said this, Donne also recognized that some people may suffer and their suffering be no use to them.

Which will you be when grief comes?