If you are divorced and civilly remarried, you are not excommunicated.

If you are divorced and civilly remarried, you are not excommunicated.

But if you are in such “irregular” situation, you cannot receive Communion.

Last but not least: excommunication is good.

Take a deep breath and repeat!

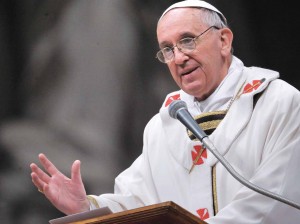

At his first General Audience after his summer break this year, Pope Francis told us that “it is necessary to have a fraternal and attentive welcome, in love and in truth, of the baptized who have established a new relationship of cohabitation after the failure” of their licit marriages. The Pope exhorted, “these persons are by no means excommunicated — they are not excommunicated! — and they should absolutely not be treated as such: they are still a part of the Church.”

With his customary aplomb, Pope Francis waded into a bit of a minefield. It may do us some good to follow—but in slow motion.

First, it may have been necessary for Francis to set the record straight, because there have been changes regarding excommunication in the circumstances the Pope described. Up until 1884, excommunication was the penalty for American Catholics who got a divorce. And, up till 1977, excommunication did apply to Catholics who divorced and remarried outside the Church.

Second, people in these “irregular” situations are no longer excommunicated, but they are still forbidden to receive the Sacrament of Communion. They are not excommunicated because they are still in the community—in fact, they have the same usual obligation to attend Mass. And they can go up to a priest or deacon to be blessed or to receive a “spiritual communion” in the pew.

Third—and this is the part we want to get to—this allows us to take a step back and look at how membership in this “community” (the Church) relates to the opposite of that, exclusion from the community, and the necessity of excommunication for the spiritual health and well-being of the community and its members, including those who may be subject of such censure.

Christ authorized the church’s exercise of the prerogative to exclude disobedient members when he instructed his disciples to confront a heretic “and if he will not even listen to the church, then count him all one with the heathen and the publican” (Matthew 18:17).

At one level, this is all elementary. The Church is a society, and every society has a right to exclude those who would undermine that society’s mission. Of course, excommunication is much more than getting kicked out of a nightclub. The Church is a special kind of “club,” we call it an ecclesiastical society. It exists for the spiritual care and guidance of its constituent members.

St. Paul puts exercises the power of excommunication with great pastoral fortitude, ordering that a man who was in an incestual relationship be cast out of the Church, “for the overthrow of his corrupt nature, so that his spirit may find salvation in the day of our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Corinthians 5:5).

Therefore, the exercise of this “penalty” is not to write-off a person and to seek to exclude them from salvation, much less is it a power play to allow one group to impose its will upon another. Instead, it is one more tool in the set of implements the church can use to extend her mission of salvation to all.

As Pope Francis expressed it, “her gaze as a teacher always draws from a mother’s heart; a heart which, enlivened by the Holy Spirit, always seeks the good and the salvation of the people.”