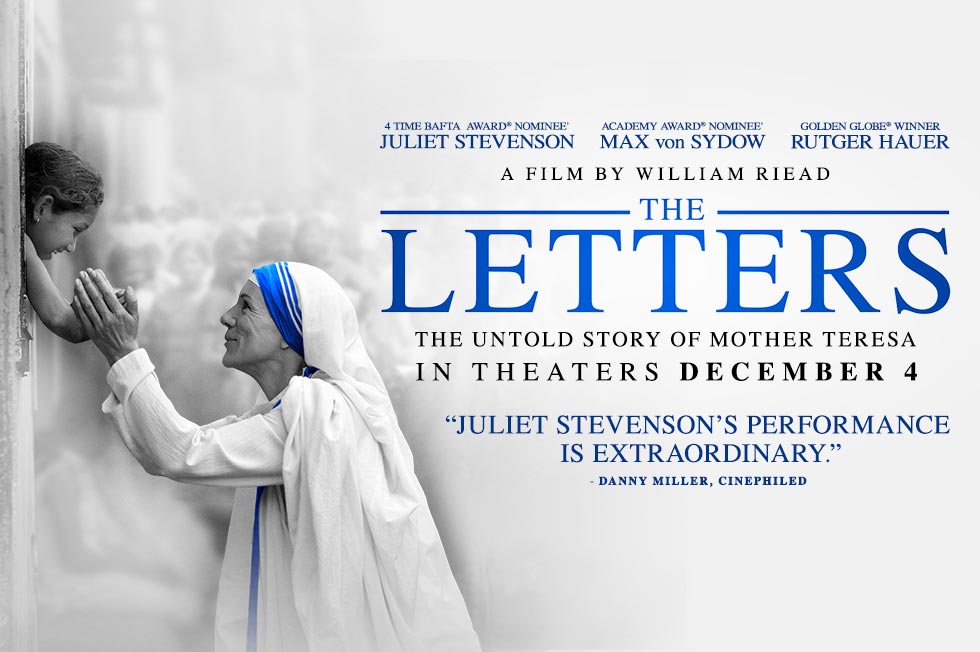

The Letters is another film about the life of Mother Teresa of Calcutta (acted with aplomb by Juliet Stevenson) — specifically that part of her life where, posthumously, personal letters that revealed her prolonged dark night of the soul surfaced. The stunning revelation is chronicled in the book Come Be My Light–The Private Writings of the Saint of Calcutta.

The Letters is another film about the life of Mother Teresa of Calcutta (acted with aplomb by Juliet Stevenson) — specifically that part of her life where, posthumously, personal letters that revealed her prolonged dark night of the soul surfaced. The stunning revelation is chronicled in the book Come Be My Light–The Private Writings of the Saint of Calcutta.

She had wanted these letters burned at her death, but, thankfully, her spiritual advisers did nothing of the sort. To know that the woman whose name is synonymous with acts of charity (“Who do you think you are? Mother Teresa?”) struggled with not just intermittent spiritual dryness but full-blown, persistent desolation, can give courage to even the most skeptical of believers and non-believers alike.

The question is: Does the film succeed in covering this omnipresent yet hidden aspect of Mother Teresa’s life? Is it actually the focus of the film? Not exactly.

Granted, it’s very difficult to externalize such a state of soul in film, especially when it’s also necessary to show her intense, concurrent missionary work and tell the story of her life. But could it have been done? Yes, and here’s how.

1. I would say that most people are familiar with the notable events of Mother Teresa’s life, so many details — although fascinating, and many never seen before in film — could have been left out.

2. It is not necessary to retell almost the entire life story of someone in a biopic. It’s better to focus on one part of their life and go deep.

3. The pace really needed to be stepped up. I felt that The Letters needed a lot of editing instead of the feel of everything unfolding in real time. Had the pace been snappier and the film unflinchingly edited, it could have accomplished much more and we would have a much better insight into who the private Mother Teresa was (perhaps even more quotes from her letters, more prayer times/work times where we could see/hear the devastation of her spirit manifested).

Otherwise? This is a well-made film, capturing the spirit and spirituality of Mother Teresa (not turning her into a secular social worker).

All that being said: 1) We can’t have too many movies about Mother Teresa. 2) A new generation wants new films and doesn’t want to have to watch old films. 3) The film succeeds as a lovely depiction of a call from God in the life of one of the 20th century’s greatest luminaries. (Mother Teresa’s vocation was a “call within a call” since she was already a professed Sister with the teaching order of Loretto.)

The film captures well her simplicity, her clever and unconquerable spirit, her seeing the face of God in the poor, and her delight in loving and serving Christ in the poor, her poor.

The film strongly brings out the moments of opposition to this “white Christian woman teacher” who lived among and almost exclusively cared for Hindus. She did not hide Jesus from them, and yet she had no ulterior motives of wanting to ultimately convert them (something Christians criticized her for!).

But there’s a difference between not wanting people to come to Christ (or being indifferent about it) and not being called to be the one to make that happen. Certainly, she would have been delighted if she sparked mass conversions to Christianity, but she was simply obeying Christ in taking care of these people. She stressed: “I am here to help.”

The work of “development” is often seen as pre-evangelization by the Catholic Church. And what greater actual evangelization could there be than putting faith, hope and love into action in the name of Christ?

These utterly destitute “untouchables” had no one but her to help them. Little by little, she won over everyone, including the Vatican (for permission to begin her new congregation) and the government of India, locally and nationally–to the point that she was given a State burial.

It may be hard for us to imagine now, but in her day, Mother Teresa was a controversial figure to some people. Catholic social justice aficionados accused her of not attacking systemic problems of poverty, not getting to the root cause of it all (thereby presuming to tell her what her vocation was/should be). A particular “progressive” Catholic periodical even calumniated her by saying she zipped around the world in a “Lear jet” with a “dishrag wrapped around her head.”

Mother, of course, always had the perfect answer for her detractors: “While we are discussing systemic causes of poverty, this man is going to die in the gutter. May I take care of him first?” She would often refuse large sums of money as “checkbook charity,” and instead invite the prospective donor to “come, experience the joy of loving.” She cared about the rich as much as the poor.

The film’s slow, reflective pace and truly lovely soundtrack makes it suitable as a retreat film or for viewing when one is in a contemplative mood. The start of the film is especially laid back as the priest-postulator of her cause for canonization (Rutger Hauer!) speaks with her spiritual director (Max von Sydow!) about the secret that Mother Teresa hid from the world: her trial of darkness.

Both priests are clearly used as devices to give us information in the baldest of ways (postulator calmly and blandly questioning spiritual director). But it gets interesting once we jump to the heart of the story, and whenever Mother Teresa (the adroit and utterly believable Stevenson nails Mother’s Albanian accent) is onscreen, it’s good.

Mother’s dark night of the soul lasted for approximately fifty years — beginning when her work with the poorest of the poor began. No wonder she famously said: “Sometimes it’s hard for me to smile at Jesus.” Yet she was ever faithful to her prayer time, her religious life, her apostolic duties, and grew her congregation, the “Missionaries of Charity” to about three thousand while she was still alive.

I remember when Mother Teresa’s spiritual struggle was made public, atheists rejoiced. Yes. Let me say that again. Atheists rejoiced that she understood them, that she was almost one of them. In fact, there was even some confusion (quickly cleared up, however) that Mother was an atheist herself!

Mother’s objective belief in God never wavered, she simply didn’t feel Him at all, and she even felt a persistent negativity that she was unacceptable to God, that He didn’t love her somehow, even though she acknowledged intellectually that God loves everyone. She experienced only God’s absence–the “via negativa”–which makes her a very postmodern saint, doesn’t it?

“If I ever become a Saint–I will surely be one of ‘darkness.’ I will continually be absent from Heaven–to light the light of those in darkness on earth.” –Mother Teresa of Calcutta

Mother Teresa had a succinct way with words, similar to Pope Francis. Her manner of speaking is well-portrayed in the film: Young nun: “I’m afraid this man is dying, Mother!” “Yes, well, we can just give him a little bit of God’s love. That’s all.” “The greatest suffering is to feel alone, unwanted, unloved.”