At the Abbey of Gethsemane in New Haven, Kentucky, the bell tower of the monastery chimed at three a.m. like Big Ben, shaking me from my bed.

At the Abbey of Gethsemane in New Haven, Kentucky, the bell tower of the monastery chimed at three a.m. like Big Ben, shaking me from my bed.

A seismic shift. What’s up with these monks? Why do they pray so early?

Because it’s their charism, the horarium of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, better known as the Trappists, a religious heritage that they have preserved for more than a thousand years.

The Trappists are one of the Church’s oldest religious communities and rarely felt the need for reform. They are who they are and that’s who and what they are: Trappists.

Change is good, a change that we can believe in, but it doesn’t come easy in a Trappist monastery. If you always do what you always did you’ll always get what you’ve always gotten.

That’s a good thing among any community of believers in the love, faith, hope, and mercy of Jesus Christ. More is never enough.

Recently I took my five-day canonical retreat at Gethsemane. Church law mandates that the cleric takes five days of retreat annually.

This is a good thing. Jesus said, “Come away by yourselves to a deserted place and rest awhile” (Mk 6:31).

The demands of priestly ministry during Lent and Easter deplete the body, mind, heart, and soul of the cleric.

Time to go.

So my spiritual director and I drove to Kentucky. Spring has sprung in the Bluegrass State but the rain pounded the region like buckshot on a copper roof.

My spiritual director and I drove through the buckle of the Bible belt where nearly every house in the region has a statue of the Virgin Mary on the porch or in the yard. I guess I was expecting to see lawn jockeys. After all, we were in Kentucky.

The whole state was gearing up for the Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs. I had other things in mind: spiritual renewal and a metanoia, a change of body, heart, soul, spirit, and

mind.

This wasn’t exactly a business trip however. I’m addition to time spent at the abbey we managed to visit local shrines. I delighted in the horse paddocks and the bourbon distilleries. When in Rome, right?

The Trappists know how to foster hospitality; community can be defined as a group of like-minded individuals who value core principles.

Is it so different with a parish? Saint Thomas Aquinas and Saint John Church and Student Center. Good music. Good preaching. Catholic education. Lenten fish fries even. This makes for a holy parish family.

In the Acts of the Apostles it is written:

“The community of believers was of one mind and heart, and no one claimed that any of his possessions was his own, but they had everything in common. With great power the Apostles bore witness to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and great favor was accorded them all” ( 4:32-33).

That sounds like us here and now in our gathering space. The imperative, however, is to take the Word of God into the world. Jesus said, “Go into the whole world and preach the gospel to every creature” (Mk 16:15).

This is love and mercy in its truest form.

This command that Jesus received from his Father he has passed on to us.

Mercy Sunday, celebrated on the Second Sunday of Easter, is a special day to acknowledge and profess God’s mercy. The right response to reception of said love is the proclamation of the gospel.

We are the community of believers of which Saint Luke writes and God’s mercy is still inexhaustible, like trying to drink from a fire hose.

The first disciples, Peter, James, John, Mary the mother of God, and Mary Magdalene, and Paul burned to preach about “Christ Jesus and him crucified” (1 Cor 2:2).

The love and mercy of God was so evident, so imperative, that the disciples couldn’t contain it. “It is impossible for us not to speak of what we have seen and heard,” Peter said (Acts 4:20).

For their faith they were imprisoned. When freed they preached the truth all the more. The community continued to grow. We hold these truths to be self evident: here we grow again in the modern church today.

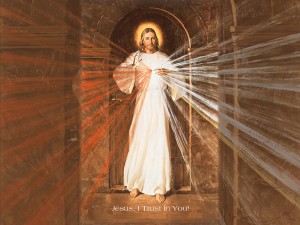

Mercy Sunday commemorates the gift of a young Polish nun named Faustina Kowalska.

In the 1930s Faustina received visions and locutions from Jesus who instructed her to record his words in her diary and share with the world the ocean of mercy flowing from the heart of our Savior.

Pope Saint John Paul the Great, another holy Pole, canonized Sister Faustina in 2000, less than seventy years after she died from tuberculosis when she was thirty-three years old.

Faustina didn’t just leave us with her sublime diary: she introduced to the world a new theology, Divine Mercy in my Soul, which makes her eligible to be declared a doctor of the church.

How I long to see that day when Faustina is declared to be a doctor of the church.

Today our community has retained the faith of the Apostles, who devoted themselves to prayer, the Word of God, and the Eucharist.

The Body and Blood of Christ is the source of love and mercy that unites the faithful to the saints. Read the writings of Faustina and you will understand real divine mercy.

The young Polish saint wrote of the love that Christ has for sinners: “The greater the sinner, the greater their right to God’s mercy.”

To Faustina Jesus said: “I am sending you with my mercy to the people of the whole world. I do not want to punish aching mankind; rather, I desire to heal it, pressing it to my merciful heart.”

Think about it.

That’s what I did for a week. In silence I meditated on these great truths of our faith. A silent retreat is not for the chatty and loquacious. Not everybody is capable of spending several days inside their own head. I’m not but I did it anyway.

The first day is getting used to the solitude. Fortunately for me, I can go days without speaking to myself, like catty spouses giving one another the silent treatment because one left salt on the kitchen counter and the other left the squeegee in the sink.

Simple, silly infractions that break up the tranquility of the domestic community.

Why can’t we all just get along?

By day two in the monastery you start believing that you could live this way forever, like the monks in the abbey. (Actually, they’re quite talkative, but who wouldn’t be after being shut up in a monastery for fifty years?)

On the third day you find yourself steeped in introspection, talking to yourself in the mirror to maintain your grip on reality and to recognize the sound of your own voice. An alarming sound when emitted in the silence.

The Abbey of Gethsemane is a popular location, thick with pilgrims who pretend they don’t see you. Eating in the refectory emphasizes the weirdness, with no sounds but that of mastication and the clinking of silverware against the plates.

Many visit Gethsemane to atone for days of wine and roses, the sixties, so there is a penitential quotient to silent retreats.

A just form of penance is to listen to yourself inside your own head for days on end. Other voices crowd the mind but those turn out to be the pilgrim next door who cheats by talking all day on their cell phone all day. False prophets.

I walked the grounds as much as my broken hip allowed. Jesus was a power-walker, a pilgrim on foot throughout the Holy Land. He made great strides.

On a hill overlooking the cloister is the grave of the great spiritual author Thomas Merton, who entered religious life in the forties in atonement for his sins but also to offer his literary talents for the good of the Church.

Merton was no different from or better than his brother monks, although he thought so.

“He was neurotic,” a Philipino monk told me. “Cloistered in his hermitage and rattling off page after page on his typewriter for the sake of posterity.

Ha! Merton’s writings pay the bills at Gethsemane in addition to the bourbon-laced fudge they set out in the refectory.

They buried him alongside many others with only a bare white cross with his name on it (“Father Louis Merton”) to mark his grave near the apse of the church.

Throughout the week I meditated on Mercy Sunday 2011, a particularly bright spot along my spiritual journey. Real days of wine and roses. I was a transitional deacon and two months out from priestly ordination.

The National Shrine of the Divine Mercy is in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, my home turf, and is a site dedicated to the school of prayer given to Faustina by Jesus.

Anticipation was high and the countdown was on. Eight more weeks to priesthood.

At the shrine I stayed with members of the Congregation of the Marians of the Immaculate Conception (they actually rejected my application; their loss), headquartered at Franciscan University in that little Vatican, known as Steubenville, Ohio.

Rock stars in the realm of Mother Angelica’s catholic media empire. That fact was not lost on them.

Mercy Sunday at the shrine is their biggest shopping day of the year. Ground crews erected tents for the bookstore and the adoration chapel and pitched the porta-potties.

EWTN set up monitors and satellite dishes. Not unlike Jerome, pundits commentated and analyzed the grace, power, and beauty of the occasion. To see them sitting on the overhang of the shrine reminded me of the press wizards covering the Master’s Tournament in Augusta or the gear heads at the Indy 500.

I tried to keep a low profile but eventually emerged from the guest house in my cassock and military haircut, which put me in violation of canon law—like Anthony Strouse.

Immediately pilgrims cornered me and refused to let me go until I blessed them. Then they begged me to autograph their books. “Autograph your books?” I asked. “I haven’t published any books. Don’t rub salt in my wounds.”

O, I see. They mistook me for one of the pundits, Father Donald Calloway, the Marian vocation director and a prolific author, who like Merton, and me, led an Augustinian lifestyle prior to priesthood.

Father Don was a surfer from San Diego, but unlike him I never got banned from the nation of Japan. I didn’t want to turn down the pilgrims so I affixed my signature to their books. Forgery?

What would you have don? They begged me. Sorry, Don. I later signed a statement relinquishing all claims to royalties.

Mercy Sunday at the shrine is huge.

Tens of thousands converge on the little church in the shire. Each year they celebrate a multilingual Mass: English, Spanish, Tagalog, German, Polish, Portuguese, Vietnamese, French, and Italian.

The gospel is proclaimed in English and Spanish but the Marian’s deacon, Hector Rodriguez, got stuck behind all the buses headed for festival from throughout the Midwest and along the eastern seaboard.

The Marians were strapped. In a panic the provincial of the order turned to me.

“Do you know any bilingual deacons in the area?” he asked me moments before the Mass.

“You’re looking at him,” I said.

“You’re hired,” he said and our handshake sealed the deal.

So they threw a dalmatic on me and I joined the forty-minute procession. The outdoor sanctuary was beautiful, bedecked with lilies and roses—and bees.

On live TV and before 25,000 pilgrims on Eden Hill before me I proclaimed the gospel in English and in Spanish (I was barely conversant back then) while the bees made honey in the lion’s head, that is, swarms of bees circled my head.

To incense the book of the gospel I poured several spoonfuls of costly incense into the thurible, hoping it would drive away the bees but it only made them angrier.

Nevertheless everything went off without a hitch. My fifteen minutes of fame at last. A great day of rejoicing.

Jesus said, “mercy triumphs over justice,” provided we choose to accept the love of God for humanity in Christ Jesus.

What did we at the shrine value that day? The same thing that the apostles held sacrosanct: the proclamation of the gospel, a word that means solidarity, faith, hope, love, and family. Truth.

It wasn’t all rosaries and incense for Faustina. For her community life was difficult. Treacherous. Spurned by her sisters, she nonetheless wrote the message of mercy that the Lord Jesus commanded her to write.

Such is the lot of many great saints. For every moment of triumph, for every instance of beauty, many souls must be trampled.

But there was great grace in the loving heart of this courageous woman. John Paul the Great recognized this. “True love and mercy,” one of our newest saints wrote, “sets no conditions; it does not calculate the costs, but simply loves.”

Don’t forget that Pope Francis canonized John Paul the Great and Pope Saint John XXIII on Mercy Sunday one year ago today.

That’s the thing with mercy: there is more than enough to go around. Double-dip if you care to. You’ll never have your fill; too much of it is never enough.

The more we immerse ourselves in the ocean of God’s mercy the thirstier we become for holiness and the true love and friendship that is community.

We become worldwide followers of Christ who is love and mercy himself.

Thomas the Apostle believed in God’s mercy because he saw the wounds in Jesus’s hands, feet, and side.

Although we have never seen the Christ the way that the first community of believers did, we love and give thanks to the Lord for we know that he is good.

As such, the psalmist writes: Give thanks to the Lord for he is good, for his mercy endures forever.

Drink it up.