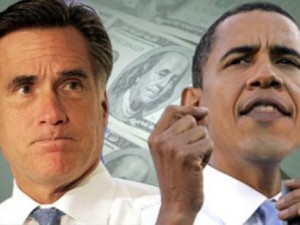

It was a fitting blunder for a candidate with authenticity issues. Asked last week on CNN if the protracted Republican primary season had eroded former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney’s ability to appeal to independents in the fall, Romney advisor Eric Fehrnstrom foolishly acknowledged a universal truth in presidential politics: the fact that candidates spend the primary season shoring up the base and the general election reaching beyond it.

It was a fitting blunder for a candidate with authenticity issues. Asked last week on CNN if the protracted Republican primary season had eroded former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney’s ability to appeal to independents in the fall, Romney advisor Eric Fehrnstrom foolishly acknowledged a universal truth in presidential politics: the fact that candidates spend the primary season shoring up the base and the general election reaching beyond it.

“It’s almost like an Etch-A-Sketch,” Ferhnstrom said. “You can kind of shake it up and restart all over again.”

The line was a gift to Romney’s critics on both the right and the left. For his primary season opponents, it underscored Romney’s rap as a conviction-challenged pragmatist whose history of changing his mind on social policy issues portends an insufficiently conservative future in the Oval Office. For supporters of President Barack Obama, Fehrnstrom’s ill-advised strategy dump paved the way for a Democratic National Committee ad that practically wrote itself. Using a red-rimmed Etch A Sketch drawing toy to frame grainy images from the Republican primary trail, the spot painted Romney as a candidate of shadowy positions that should spook voters.

And that would have been that — Romney camp takes the prize for political misstep of the month — were it not for an oddly similar blunder by his Democratic rival just days later. On Monday, while speaking to Russian President Dmitry Medvedev about U.S. plans for a missile defense system that Russia opposes, Obama offered what he thought was a private comment for Medvedev to relay to Prime Minister Vladimir Putin.

“On all these issues, but particularly missile defense, this, this can be solved but it’s important for him to give me space,” Obama confided, not realizing the microphones were on. “This is my last election. After my election I have more flexibility.”

Obama and his aides later dismissed the comment as inconsequential, a mere nod to the limits of diplomatic talks during an election year. But like Fehrnstrom’s Etch A Sketch goof, Obama’s slip highlighted a longstanding concern about the president in the center-right nation he governs: the suspicion that for all the controversy Obama has generated in his first term, his second one could bring far more unpleasant surprises.

In a sense, the Obama and Romney gaffes were strikingly similar. Both compounded concerns that the candidate who wins our votes in November will not be the one governing us come January.

In Obama’s case, Americans already have learned this lesson once. After selling himself in 2008 as a post-partisan problem-solver dedicated to healing America’s divisions and getting the economy back on track, Obama has proved surprisingly ineffectual on economic issues and alarmingly ideological on social ones.

Although first-term presidents typically temper their partisan excesses and authoritarian impulses until after they have cleared the hurdle of reelection, Obama has not. From his unprecedented public rebuke of the Supreme Court justices sitting before him at his 2010 State of the Union address to his ramrodding of Obamacare and his more recent refusal to brook any meaningful compromise on a contraceptive mandate greeted by nationwide protests, he has stoked fears about the “flexibility” he might exercise beginning in January 2013. It’s a flexibility that could extend far beyond the realm of foreign policy, manifesting in a push for exactly the sort of radical social policies and big-government power grabs that animate the most liberal fringe of his party — the hard-core activists who have kept faith with him because they believe he is, deep down, one of them.

Romney, of course, faces the opposite challenge: distrust from the conservative party faithful who fear he is not one of them. They worry that this former management consultant harbors more passion for data and consensus than conservative principles, that his true views are closer to those of the swing voters he would court in a general election than the Republican primary voters he is wooing now. They worry, in other words, that Romney actually is what Obama only claims to be: a pragmatist.

Assuming the delegate math continues its current trajectory, November’s presidential contest will be a match between a Republican who may not be as conservative as he claims and a Democrat who may be far more liberal than he lets on. It’s not an ideal situation for Republicans, who would rather see a riveting, rock-ribbed conservative stalwart championing their cause against Obama. Yet backlash against Obama’s policies surely will turn out the vote among committed conservatives, just as passionate allegiance to him will turn out liberal partisans.

As usual, independents will decide the election. And independents weighing the rap against these two flawed contenders must ask themselves: What’s the bigger gamble, a closet centrist or a closet radical?

If swing voters ask that question, and vote accordingly, Romney may find that his primary season Achilles heel has become his saving grace. And Obama may find that his presumptuous promises of second-term flexibility never come to pass.