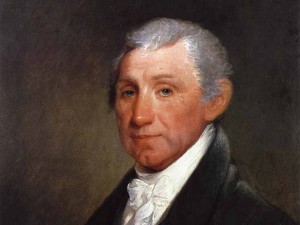

Sunday, April 28, marks the 255th anniversary of President James Monroe’s birth in 1758.

Recently, I had the pleasure of reading one of Harlow Giles Unger’s thorough biographies of key figures in the era of America’s founding. In reading “The Last Founding Father: James Monroe and a Nation’s Call to Greatness,” I found myself wondering: How have we let this great patriot become a forgotten man?

Monroe’s military service alone made him a hero. When he was 18 and newly matriculated at William and Mary College, and the Second Continental Congress proclaimed the Declaration of Independence, he suspended his education to enlist in the Virginia infantry.

He arrived in New York to find that the British army had just decimated Washington’s army at Harlem Heights—having killed 1,500 out of 5,000 troops. Two days later, Monroe and his fellow Virginia sharpshooters repelled a British advance, marking the first time in the War for Independence that Americans had whooped the British, forcing the redcoats to turn tail and run for their lives.

Monroe played a key role in Washington’s famous 1776 Christmas night sortie across the Delaware River. The teenaged Monroe was the co-leader, with one of Washington’s cousins, of an advance party of 50 that had crossed the river ahead of the rest of Washington’s troops, and then captured the two strategically placed cannons that defended the Hessian military camp outside of Trenton. Though seriously wounded by a musket shot, Monroe stood his ground, repelling repeated Hessian attempts to recapture the big guns, thereby saving many American lives (including, possibly, Washington’s), and thereby making that indispensable, resounding victory possible.

During the War of 1812, 38 years later, Monroe was in his mid-50s. At that time, he was serving in the Madison administration as both Secretary of State and (after a disastrous performance of his predecessor had almost resulted in total defeat) as Secretary of War. Inheriting a dire military situation in 1814, Monroe virtually single-handedly altered the course of the war. He rallied the country’s disorganized military forces, developed a country-saving military strategy, and personally led American troops from horseback from dawn until dusk—which prevented the total collapse of American resistance to the British by dint of his courage, inspirational leadership, and military genius.

Monroe’s marriage was one of the great love stories in presidential history. He and Elizabeth—who might have been the only First Lady more beautiful and glamorous than Jackie Kennedy, and who displayed heroic courage by intervening in the nick of time to save Lafayette’s wife, Adrienne, from the guillotine—shared a decades-long tender and devoted mutual love.

James Monroe may hold the record for the highest number of offices held during his career in public service. He was either elected or appointed to the following offices: 1782, Virginia legislature; 1790, U.S. Senate; 1794, Minister to France; 1803, Minister to France and Spain whose initiative resulted in the Louisiana Purchase; 1803, Minister to England; 1810, elected to the Virginia legislature a third time; 1811, elected governor of Virginia a fourth time; 1811 becomes U.S. Secretary of State; 1812-13, named acting Secretary of War and in 1814, actual Secretary of War while also remaining Secretary of State; 1816, elected president; 1820, re-elected without opposition—the only American other than George Washington to stand unopposed for the presidency.

It is that last accomplishment—being elected without opposition to the presidency—that is most remarkable. After the bruising election campaign we recently passed through, we may wonder how it was possible that nobody bothered to run against Monroe. Yes, he was an exceptional man, but even great men have enemies.

I think the reason Monroe ran unopposed was that nobody at that time felt threatened by the federal government. In 1820, Uncle Sam was still confined to original duties of keeping Americans safe and upholding contracts and property rights. In other words, in the minds of free Americans, there was neither a handout to be gained from the federal government nor the threat of confiscation of a portion of one’s property for redistribution to special interests. In short, the government was limited, unobtrusive, and benign.

Today, by contrast, the federal government is a predatory aggressor against property rights, and myriad special interests engage in an angry, perpetual battle to see who can take what from whom. Monroe had the good fortune to be president when America was America and not this sorry variation of a demoralized European welfare state.

The amazing life story of James Monroe, the fifth president of the United States, would not be complete without mentioning that he passed from this world on the Fourth of July, 1831 — five years to the day after his fellow presidents Adams and Jefferson. What a fitting conclusion to the life of a principled patriot who gave his whole adult life to serving his country and upholding our most noble ideals.

[Editor’s note: a version of this article first appeared at Forbes.com.]