“Do you fast? Then feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, visit the sick, do not forget the imprisoned, have pity on the tortured, comfort those who grieve and who weep, be merciful, humble, kind, calm, patient, sympathetic, forgiving, reverent, truthful and pious, so that God might accept your fasting and might plentifully grant you the fruits of repentance. Fasting of the body is food for the soul.” —St. Basil the Great, 329-379 A.D.

“Do you fast? Then feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, visit the sick, do not forget the imprisoned, have pity on the tortured, comfort those who grieve and who weep, be merciful, humble, kind, calm, patient, sympathetic, forgiving, reverent, truthful and pious, so that God might accept your fasting and might plentifully grant you the fruits of repentance. Fasting of the body is food for the soul.” —St. Basil the Great, 329-379 A.D.

“Prayer, fasting, vigils, and all other Christian practices, however good they are in themselves, do not constitute the goal of our Christian life, although they serve as a necessary means to its attainment. The true goal of our Christian life consists in the acquisition of the Holy Spirit of God. Fasting, vigils, prayers, alms-giving and all good deeds done for the sake of Christ are but means for the acquisition of the Holy Spirit of God. But note, my son, that only a good deed done for the sake of Christ brings us the fruits of the Holy Spirit. All that is done, if it is not for Christ’s sake, although it may be good, brings us no reward in the life to come, nor does it give us God’s grace in the present life.” —St. Seraphim of Sarov (a famous and highly revered Russian Orthodox saint, 1754-1833 A.D.)

Today Pope Francis took the first, dramatic public action of his pontificate.

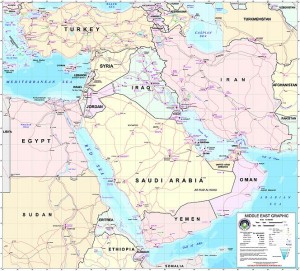

During his Sunday Angelus message, he called upon Catholics everywhere — and also all Christians and all men and women of good will — to join him in a day of prayer and fasting for peace in Syria, where civil war has left thousands dead, and the involvement of other powers threatens a still wider war, this coming Saturday, September 7, the vigil of the Feast of the Birth of Mary, the Mother of God.

He asked Catholics everywhere to fast on Saturday along with him, and also to gather in their various parish churches to participate with him as he prays in Rome.

So the world will see something dramatic this Saturday: Pope Francis himself will be in St. Peter’s Square on Saturday evening from 7 p.m. until midnight, praying and fasting with the faithful of Rome and of the whole world, for peace in Syria and in the whole world.

(Some of the logistics are yet clear. Those Saturday evening hours in Rome would correspond to Saturday afternoon from 1 p.m. to 6 p.m. in the eastern United States; it would seem that those hours would be the ones to pray along with the Pope. It is not clear whether the Pope will be present throughout the evening in St. Peter’s Square. Nor is it clear whether he will be praying out loud or in silence during those five hours, or in some combination of the two. Such details have not yet been released.)

This decision to call for a day of prayer and fasting reveals much about the man who is Pope Francis, and about the pontificate he is now truly beginning.

His action is marked by a fusion of the “traditional” and the “modern.”

His action draws upon 2,000 years of Catholic ascetical tradition, and in this sense is a highly traditional act.

Catholic tradition speaks of the “divinization” of fallen mankind through spiritual practices like prayer and fasting, and Pope Francis is asking all Catholics to join him in these traditional spiritual practices.

But his action also reflects the modern vision which, in the post-conciliar period, in response to (sometimes unjust) criticisms of traditional spirituality as too “inward-looking” and “self-referential” in the midst of a suffering world, has challenged Christians to work to relieve concrete human suffering in this present time.

And since few things cause as much suffering to men as the violence of war, with all of its “collateral damage” — wounded and dying children, the ruin of villages and towns, the destruction of churches, mosques, temples, schools, the pollution of air and water and earth with things like the depleted uranium used in modern bullets to make them harder, able to penetrate armor (a radioactive substance which remains harmful, causing genetic defects in embryos, for decades) — Pope Francis has called on Catholics, and others of good will, to join him in many hours of prayer, and of abstention from food, for the end to the civil war in Syria, for the avoidance of a wider war there, and for peace generally throughout the world.

So his call for a day of prayer and fasting — drawing close to God by withdrawing from the things of this world, entering into the silence of prayer to escape the noise and distraction of this life, abstaining from food to recognize the fragility and dependency of man’s existence — is traditional.

And his call for peace in Syria is modern, as modern as the headlines of this moment.

“Those terrible images from recent days are burned into my mind and heart”

Pope Francis’s call is urgent.

He is not asking for us to prepare for something six months or 12 months from now, but for something six days from now.

In his talk today, the Pope spoke with great urgency and passion.

He said openly that he was concerned about the use of chemical weapons last week in Syria.

“With utmost firmness I condemn the use of chemical weapons,” the Pope said. “I tell you that those terrible images from recent days are burned into my mind and heart.”

But he also said, in an evident reference to the possible widening of the war by strikes from America, and a possible reaction from the Russians (who support the Assad regime), or others, including Iran (Syria’s ally) and Israel (which might wish to launch a preemptive strike if it feared others might be preparing to launch a strike against Israel), that he is “anguished by the dramatic developments which are looming.”

The Pope is clearly worried that events could spin badly out of control.

This is not the place to discuss all the ambiguities surrounding the events in Syria, which make any final judgment on the situation there extremely problematic. (The ambiguity of the situation is shown by the very close vote three days ago in the British Parliament not to join in a possible US-led cruise missile strike against the Assad regime, which had been expected perhaps even during this weekend, and was only postponed at the last minute by President Obama, who now says he will seek Congressional approval for such an action; there was no unanimous, or nearly unanimous, vote in Britain. Opinion was almost evenly divided. So it is clear that the decision is not an evident one.)

We can limit our reflection to two ambiguities. The first concerns the use of chemical weapons; the second concerns US law in regard to support for the so-called “Al Qaeda” militant Islamic organization.

Regarding the first point, there are various reports that it was the rebels in Syria, not the Syrian government, which made use of Sarin gas in killing 200, and perhaps as many as 1,000, civilians, then casting blame on the government (this is referred to as a “false flag” event, in which a deceptive action is carried out by one power to cast blame on another power). This means that it is not clear whether it would be in any way “just” to retaliate against the Assad regime for this terrible gas attack.

Regarding the second point, there are reports that these rebels are primarily from outside Syria and represent “Al Qaeda” forces (if “Al Qaeda” may be said to be so well-organized as to even have a defined membership). But “Al Qaeda” is described in the 2001 Patriot Act of the United States as a force inimical to the US, so much so that any support of Al Qaeda by Americans is envisioned in that Act as treason against America; so it would seem that, if it is true that the rebels are part of “Al Qaeda,” any action in support of them would be an act of treason against America under US law.

But the precise details of this situation concern Pope Francis less than the general principle: that the resolution of disputes by violence, by war, inevitably brings about “collateral damage” and great suffering. He makes that clear in his remarks.

Pope Francis wishes to be a peace-maker, and to help others find possible ways to make peace.

And he is willing to make this dramatic gesture of abstaining from food for a day — fasting — and praying for a day, in order to seek God’s assistance in this very dangerous and not only potentially but already tragic situation.

It would be remarkable if other religious leaders would take this opportunity to announce that they too will come together to pray and fast with the Pope at this special time, on Saturday, September 7.

“Fasting is a medicine”

“Fasting is a medicine. But like all medicines, though it be very profitable to the person who knows how to use it, it frequently becomes useless (and even harmful) in the hands of him who is unskillful in its use. For the honor of fasting consists not in abstinence from food, but in withdrawing from sinful practices, since he who limits his fasting only to abstinence from meats is one who especially disparages fasting. Do you fast? Give me proof of it by your works. If you see a poor man, take pity on him. If you see an enemy, be reconciled with him. If you see a friend gaining honor, do not be jealous of him. And let not only the mouth fast, but also the eye and the ear and the feet and the hands and all members of your bodies.” —St. John Chrysostom

The word “fast” in the Bible is from the Hebrew word sum, meaning “to cover” the mouth, or from the Greek word nesteuo, meaning “to abstain.”

For spiritual purposes, it means to go without eating and drinking (Esther 4:16).

The Day of Atonement — also called “the Fast” (Acts 27:9) — is the only fast day commanded by God (Leviticus 23:27), though other Jewish fast days are mentioned in the Bible.

Also, personal fasts are clearly expected of Christ’s disciples (Matthew 9:14-15: “Then came to him the disciples of John, saying, Why do we and the Pharisees fast oft, but thy disciples fast not? And Jesus said unto them, Can the children of the bride chamber mourn, as long as the bridegroom is with them? But the days will come, when the bridegroom shall be taken from them, and then shall they fast.”).

The Bible records that great men of faith such as Moses, Elijah, Daniel, Paul and Jesus Himself fasted so that they might draw closer to God (Exodus 34:28; 1 Kings 19:8; Daniel 9:3; Daniel 10:2-3; 2 Corinthians 11:27; Matthew 4:2).

James tells us, “Draw near to God and He will draw near to you” (James 4:8).

Here is the full text of the Holy Father’s Angelus appeal.

[Editor’s note: see also this related article.]