Pope Francis has asked Catholics to meditate on poverty this Lenten season, by focusing his message for Lent on St. Paul’s words to the Corinthians, that Christ “became poor, so that by his poverty you might become rich” (2 Cor. 8:9). The Pope’s emphasis on poverty dates back to the earliest days of his Pontificate, when he declared, “How I would like a Church which is poor and for the poor!”

Pope Francis has asked Catholics to meditate on poverty this Lenten season, by focusing his message for Lent on St. Paul’s words to the Corinthians, that Christ “became poor, so that by his poverty you might become rich” (2 Cor. 8:9). The Pope’s emphasis on poverty dates back to the earliest days of his Pontificate, when he declared, “How I would like a Church which is poor and for the poor!”

Within the first forty days of his reign, Francis “unblocked” the canonization cause of Archbishop Óscar A. Romero of El Salvador—a churchman known for his radical commitment to the poor—further evidencing Francis’ desire to make poverty a hallmark of his papacy.

In my Lenten series, «Septem Sermones ad Pauperem» (“Seven Sermons to the Poor”) at the Super Martyrio Blog, I have analyzed Romero’s final sermons, from which I have extracted seven themes that can help us unpack Pope Francis’ Lenten Message:

Poverty is a central feature of Christ

Poverty is a valued spiritual trait in the Church

Poverty is appropriate for Lent

Poverty points us to God

Poverty sheds light on sin

Poverty is not to be confused with misery; and—

Mere poverty is not enough

First, Pope Francis’ Lenten message is wisely Christ-centered. In the first section of his message, entitled “Christ’s grace,” the Pontiff draws our attention to Christ’s poverty, which he contrasts with Christ’s wealth. “Jesus’ wealth lies in his being the Son,” the Pontiff tells us: “his unique relationship with the Father” is what makes Him rich.

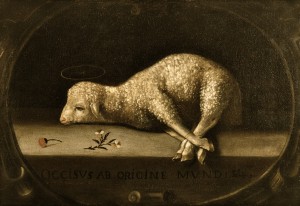

By contrast, Christ’s poverty “is his way of loving us” by suffering for our cause. Archbishop Romero taught this lesson using two of the great images of Christ in the Lent readings. The first is Jesus at the Transfiguration, when He appears atop the holy mountain while a voice from a cloud declares “This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased” (Matthew 17:5).

Romero thought long and hard about this passage, as the Transfiguration is El Salvador’s patronal feast and he had been preaching about it since the 1950s. Romero calls his preaching “Transfiguration Theology,” with this celestial image as its paragon (Mar. 2, 1980 sermon).

The other image is Christ fasting in the desert and rejecting Satan’s temptations of power, success and domination over the kingdoms of the world. Instead, Jesus embraces poverty: hunger, obscurity and insignificance, rather than give in to “the idolatry of money, the idolatry of power and any pretext that would have people kneel before these false gods,” Romero says. (Id.)

Pope Benedict XVI agrees, noting that Satan’s proposal is “far from God’s plan because it passes through power, success and domination rather than the total gift of himself on the Cross” (General Audience, Feb. 22, 2012). The Transfiguration shows us Jesus’ wealth; the desert sojourn shows us Christ’s poverty, voluntarily borne.

Second, a necessary corollary to the premise that poverty is a central characteristic of Christ is that poverty is a desirable spiritual trait for us. “God’s wealth passes not through our wealth,” writes Pope Francis, “but invariably and exclusively through our personal and communal poverty, enlivened by the Spirit of Christ.” Romero expands, saying that “Poverty is a spirituality, a Christian attitude and the soul’s openness to God.”

This is why poverty is one of the things Christ tells us to do if we seek to be perfect (Matthew 19:21), and one of the vows taken by religious communities in the Church (Code of Canon Law § 600). Why Jesus tells us “Blessed are the poor” (Luke 6:20). The powerful “are on their knees before—and, trust in—false idols” of money, power, and pleasure, Romero says. But, “you who are destitute of everything, know that the poorer you are, the more you possess God’s kingdom, provided you truly live that spirituality” (Feb. 17, 1980 sermon).

Third, the spirit of poverty is proper to the season of Lent. “Lent is a fitting time for self-denial; we would do well to ask ourselves what we can give up in order to help and enrich others by our own poverty,” Pope Francis writes. Romero points out that fasting and prayer are “perennial Christian practices,” to which the Church calls the faithful, “but adapted to the circumstances of each people” (Mar. 2, 1980 sermon.) He cites Pope Paul VI, who said the affluent should strip themselves of superfluous wealth in solidarity with the poor, while “third-world peoples, undernourished as they are, living in a perpetual Lent,” can offer their existing poverty as their humble Lenten sacrifice. (Id.)

Fourth, drawing closer to the poor will bring us closer to Christ. Romero said that, “As we draw near to the poor, we find we are gradually uncovering the genuine face of the Suffering Servant of Yahweh” (Feb. 17, 1980 sermon). In his youth, Romero studied asceticism, which promotes self-denial as a way to find God. Throughout his life, Romero practiced abstinence and mortification of the flesh.

The ultimate expression of Romero’s asceticism became his radical identification with the poor, but his motivation was the same: “In the poor and outcast we see Christ’s face,” says Pope Francis in his Lenten Message.

Fifth, poverty helps us to confront the horror of sin. In our world, “poverty is a denunciation of sin,” Romero preached, because the existence of poverty leads us to question its causes, which expose our sins. “Sin killed the Son of God,” Romero declares, “and sin is what continues to kill the children of God.” (Id.) Pope Francis concurs: “When power, luxury and money become idols, they take priority over the need for a fair distribution of wealth.”

Sixth, poverty is one thing and misery is quite another. “Destitution is not the same as poverty,” Pope Francis warns: “destitution is poverty without faith, without support, without hope” (emphasis added). Romero cited the Latin American Bishops at Medellin (1968) in declaring that, “Poverty, as a lack of the goods of this world necessary to live worthily as men and women is, in itself, evil.” (Id.) This is not the poverty we are meant to promote during Lent.

And finally—seventh—Pope Francis points out that depriving ourselves is not enough. “Let us not forget that real poverty hurts,” he writes: “I distrust a charity that costs nothing and does not hurt.” Archbishop Romero adds that we must give our poverty (whether taken on, or preexisting) a penitential sense: “showing God that we are willing to deprive ourselves of something in order to make amends for our excessive ways.” (Id.)

We should “not put the emphasis on eating or not eating meat, but rather that we focus on the idea of mortification and sharing the little that we have with those who have less.” (Id.) The abnegation has to be from the heart.

These seven lessons about poverty from Pope Francis and Archbishop Romero show us that solidarity with the poor is all about drawing closer to Christ, who became poor to draw closer to us.