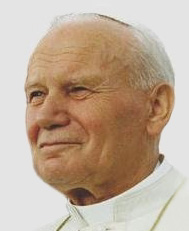

The swiftness of Pope John Paul II’s rise from popular pope to “Blessed John Paul” […] sparked widespread debate in advance of his beatification [Divine Mercy] Sunday. Critics charge that his failures in addressing the clergy sex abuse crisis should disqualify him from beatification, or at least stall the process. Defenders say his administrative shortcomings do not change the fact that he embodied “heroic Christian virtue,” the key requirement for beatification.

The swiftness of Pope John Paul II’s rise from popular pope to “Blessed John Paul” […] sparked widespread debate in advance of his beatification [Divine Mercy] Sunday. Critics charge that his failures in addressing the clergy sex abuse crisis should disqualify him from beatification, or at least stall the process. Defenders say his administrative shortcomings do not change the fact that he embodied “heroic Christian virtue,” the key requirement for beatification.

The Vatican has emphasized that John Paul is being honored for his personal holiness, not his papal accomplishments. Still, discussion of John Paul’s papal legacy is inevitable at a time like this. Disputes over the abuse crisis have dominated that discussion, but another issue often looms large: the question of John Paul’s attitude toward women.

For social liberals who view the Catholic Church through the lens of contemporary gender politics, John Paul’s 26-year reign was a puzzling defeat. The pope tirelessly defended the rights of workers, religious minorities and citizens oppressed by totalitarian regimes. Yet he failed to carry the progressive banner in the battles that many consider litmus tests for leaders today. He crusaded against abortion, defended sex differences as an immutable reality and flatly rejected the possibility of women priests.

John Paul’s feminist critics often regard him as the ecclesial equivalent of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a man whose towering intellect brought him to the brink of enlightenment but whose stubborn, Old World sensibilities prevented him from giving women their due. That assessment would be easier to swallow were it not for the curious phenomenon that began during John Paul’s lifetime and has exploded since his death: the rising numbers of Catholic women who proclaim themselves “new feminists” in the mold of the late pope.

You can find them across America and all over the Internet, this eclectic mix of college students, seasoned Catholic “reverts,” accomplished professionals and full-time mothers. They blog about the “feminine genius,” swap conversion stories about the first time they read John Paul’s writings on women and organize conferences at schools such as the University of Notre Dame and Ave Maria University inspired by his writings and those of the Christian feminist and fellow philosopher he canonized, Edith Stein. They speak of John Paul as the man who helped them find true freedom by embracing, rather than running from, their uniqueness as women.

John Paul once joked that he was “the feminist pope.” Among his credentials for that claim was his 1988 Apostolic Letter, “On the Dignity and Vocation of Women,” the first document of the Catholic Church’s pontifical Magisterium dedicated totally to women. In that letter, John Paul lamented the tendency of our technological age to prize things more than people and to measure a person’s worth according to what he produces. He believed that this mindset leads to a loss of respect for the intrinsic dignity of the human person and the very values that make us human. And he thought women were uniquely positioned to combat it.

A woman can do so, John Paul said, by drawing upon her natural inclination to focus on the concrete and the personal, her tendency to intuitively grasp the dignity of every human person. These inclinations, which he connected to a woman’s capacity for both physical and spiritual motherhood and characterized as her “feminine genius,” can be used to convert our society from one that values people for what they have and do to one that values people for who they are.

John Paul mentioned this “feminine genius” again in his 1995 encyclical, “The Gospel of Life,” in which he argued that women have a “unique and decisive” role to play in transforming culture. He called on women “to promote a ‘new feminism’ which rejects the temptation of imitating models of ‘male domination,’ in order to acknowledge and affirm the true genius of women in every aspect of the life of society, and overcome all discrimination, violence and exploitation.”

In a world that says women must prove their equality by tearing men down or imitating boys behaving badly, John Paul said that a woman finds her fulfillment by becoming more fully what God created her to be: a human being who bears God’s image to the world in a distinctively feminine way. He urged women to exercise their “genius” in public life as well as private. Yet he cautioned against confusing the equality of the sexes with sameness of roles. It is no more unjust for women to be excluded from the paternity of the priesthood, John Paul argued, than for men to be denied the maternal privilege of conceiving and bearing children.

John Paul’s arguments did not win over everyone, but they have resonated with an increasingly wide swath of American women. Tired of the me-first mentality and androgynous tenor of establishment feminism, these “JP2 feminists” fondly remember the pope who helped them rediscover the joy of being a woman.

(© 2011 Colleen Carroll Campbell)