The Roman galley cruised through the surf and flotsam into the harbor on the island of Patmos in the Aegean Sea. While the galley slaves slumped exhausted across their oars, the convicts disembarked and formed a long chain bound for the penal colony and marched up the road to the sound of the lash and the soldiers’s hollers: Hoc!

The Roman galley cruised through the surf and flotsam into the harbor on the island of Patmos in the Aegean Sea. While the galley slaves slumped exhausted across their oars, the convicts disembarked and formed a long chain bound for the penal colony and marched up the road to the sound of the lash and the soldiers’s hollers: Hoc!

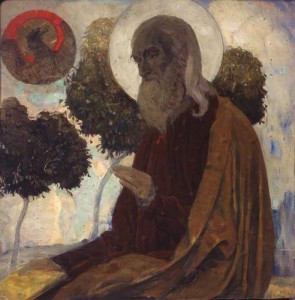

These men were sentenced to work in the stone quarries, to sleep in caves, and to live out their sentences in the confines of this island, rocky, desolate, and dry. Among the slaves was John, condemned as a Christian for his missionary activities in the seven cities of Asia Minor, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Smyrna, Philadelphia, Laodicea, and Ephesus. [1] Such was calling from the beginning, since the day when he first met the Lord, a man who from the beginning was with God. From the cliffs John looked across the sea toward the churches to which he addressed letters contained in the Book of Revelation he was writing while imprisoned. The labor imposed upon him by the guards was grueling, the setting cold and loveless, but it was temporary.

“John” in the New Testament is a complex and mysterious persona. Several identities are affixed to him: John the son of Zebedee; the beloved disciple, the Evangelist; the Elder, and John the Divine. The Johannine corpus of writing, the gospel, the apocalypse, and the three letters, form a powerful and enigmatic body of work in the New Testament canon. These works “open a window on one period in the life of the Johannine community, Christian groups that earlier had produced the Gospel of John. Indeed, the interpretations of these writings depends in large measure on constructing their historical context from the spare clues they supply.” [2] John, a highly gifted and versatile writer, possessed superior literary abilities by virtue of the grace conferred on him by Christ, who opened his mind to understand the Scriptures (Luke 24:45) and at Pentecost when he received the Holy Spirit, equipping him to assist the work of the Spirit and to renew the face of the earth. Because he knew Jesus in the flesh he was able to write about him through experience, from images carved sharply into his memories from long ago when he was the disciple whom Jesus loved.

John wrote The First Letter of Saint John to combat heresies and to deepen the spirituality of the Church. Time away from the decadence of the world prepared him to write. “If someone who has worldly means sees a brother in need and refuses him compassion, how can the love of God remain in him? Children, let us love not in word or speech but in deed and truth” (1 John 3:17). Unlike his brother apostles, John did not have the opportunity to save a brother’s life by dying for them, but he did the next best thing: he helped one to meet their needs. To give to another who has need is to keep them alive, and thereby following the Lord’s example of self-sacrificing love. “We know love by this, that he laid down his life for us — and we ought to lay down our lives for one another” (3:16). This John learned in the confines of the island where sorrow and agony abounded.

The world — kosmos in the Greek — represents the valueless system of priorities that exclude God, a moral and spiritual black hole constructed by antichrists to draw the lover of God away from the object of their affection. The world appeals to all people, believers and nonbelievers, and steals their affection and loyalty. Like the wizard behind the curtain, Satan works the levers and true believers in the Father and the Son must shun the world and its allurements and turn away. “All that is in the world, sensual lust, enticement for the eyes, and a pretentious life, is not from the Father but is from the world. Yet the world and its enticements are passing away. But whoever does the will of God remains forever” (2:16).

Upon his release from prison John boarded another galley and returned to Ephesus, back into the world, where he wrote the Gospel According to John and the three letters known as 1, 2, and 3 John. Reliable tradition says this happened in AD 95. The authenticity of the first letter is well-documented; its internal structure and language confirms it was written by the author of the Gospel According to John. Saints Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, and even Origen affirmed that the writer of the letter is the same John that wrote the fourth gospel. On the grounds of style and vocabulary, and what might be called “literary personality,” [3] it is agreed that these works were produced by the same school of Johannine spirituality. The structure and the language are direct and repetitious, contrasting light and darkness, the Christian in the world, and error versus truth that threaten the faith and dilute the meaning of being a Christian. The synthesis of these ideas creates an intense religious conviction expressed in simple statements of truth. “Do not love the world or the things of this world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him” (1 John 2:15). In the world is all that is hostile toward God and alienated from him. Love of the world and love of God are mutually exclusive. This John reflected on in greater capacity during his sentence on the island where he lived away from the world for so long. To be a lover of the world is to be at enmity with God (James 4:4).

John reportedly died at a very old age. “The rumor spread in the community that this disciple would not die. Yet Jesus did not say that he would not die, but ‘If it is my will that he remain until I came, what is that to you?’” (John 21:23). If, however, the son of Zebedee, the beloved disciple lived for any length of time during the reign of the Roman emperor Domitian (AD 81-96), then it is possible that he was the visionary who wrote the Book of Revelation and then returned to Ephesus where he composed the gospel and the three letters.

The characteristic modesty of the Seer shines through. Casting himself as the first-person peripheral narrator, John writes: “There are also many other things that Jesus did, but if these were to be described individually, I do not think that the whole world would contain the books that would be written” (John 21:25). One thing is certain: no writer in the New Testament holds with greater intensity the full reality of the Incarnation as does John.

We declare to you what was heard from the beginning, what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked at and touched with our hands, concerning the word of life. (I John 1:1)

To John, Jesus is the preexistent and incarnate Word, the Logos. Of this he is certain because he has known the Lord from the beginning. He urges his readers to remain with what they have heard from the beginning from him and other Christian leaders. This means believing in the physical Jesus who also is the Son of God and in the saving value of his death.

[1] Brownrigg, Ronald. Who’s Who in the New Testament. Avenel, N.J.: Wing Books, 1971.

[2] Culpepper, R. Alan. “1, 2, 3 John”. Harper-Collins Biblical Commentary. San Francisco: HarperSanFranciso, 2000.

[3] Illustrated Dictionary and Concordance of the Bible. New Revised Edition. Geoffrey Wigoder, Ph.D., gen. ed. New York: Sterling Publishing, 2005.